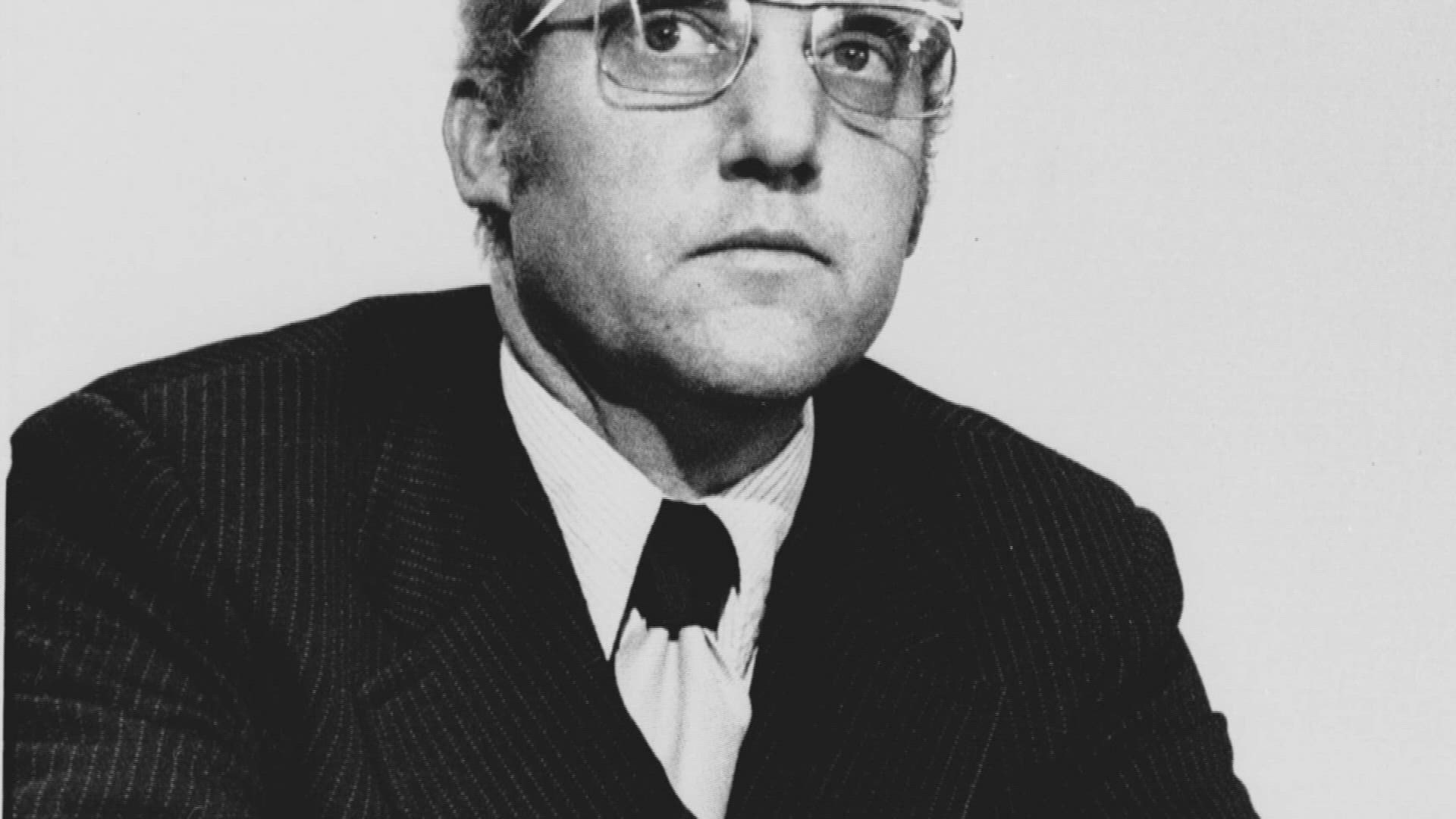

NEW ORLEANS — Moon Landrieu, the two-term mayor of New Orleans who ushered in an era of integration and revitalization of city government in the 1970s and fathered a political dynasty that includes a mayor and U.S. Senator, died Monday morning, his family told WWL-TV Political Analyst Clancy DuBos. He was 92.

Landrieu was the patriarch of the political family sometimes called the “Cajun Kennedys.” His nine children with his wife Verna include former New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu, who is currently the White House infrastructure coordinator and who previously served as Louisiana’s lieutenant governor and a state representative.

Landrieu’s daughter Mary served three terms in the U.S. Senate in addition to serving as Louisiana state treasurer and a state representative. Another daughter, Madeleine, is a former state appellate court judge now serving as dean of Loyola University New Orleans College of Law, while son Maurice Jr. is an Assistant U.S. Attorney. Several of Landrieu’s other children are civic and business leaders in their own right.

Best known for serving two terms as the city’s mayor from 1970 to 1978, Moon Landrieu’s political resume also includes stints as a Louisiana state representative, New Orleans City Councilman and judge on Louisiana’s Fourth Circuit Court of Appeal. After leaving the mayor’s office in 1978, Landrieu was named U.S. Secretary of Housing and Urban Development during the final two years of President Jimmy Carter’s administration.

A lifelong Democrat, Landrieu campaigned for mayor of New Orleans on a solidly progressive, pro-civil rights platform. He was a rarity: a white Louisiana politician outspoken in his support of civil rights. His stance earned him a near-monolithic majority of Black votes in the 1969 mayoral election and propelled him into office. Once elected mayor, Landrieu was credited with opening City Hall to African Americans by appointing Black leaders to many key positions, including department heads and chief administrative officer, the highest-ranking mayoral appointee.

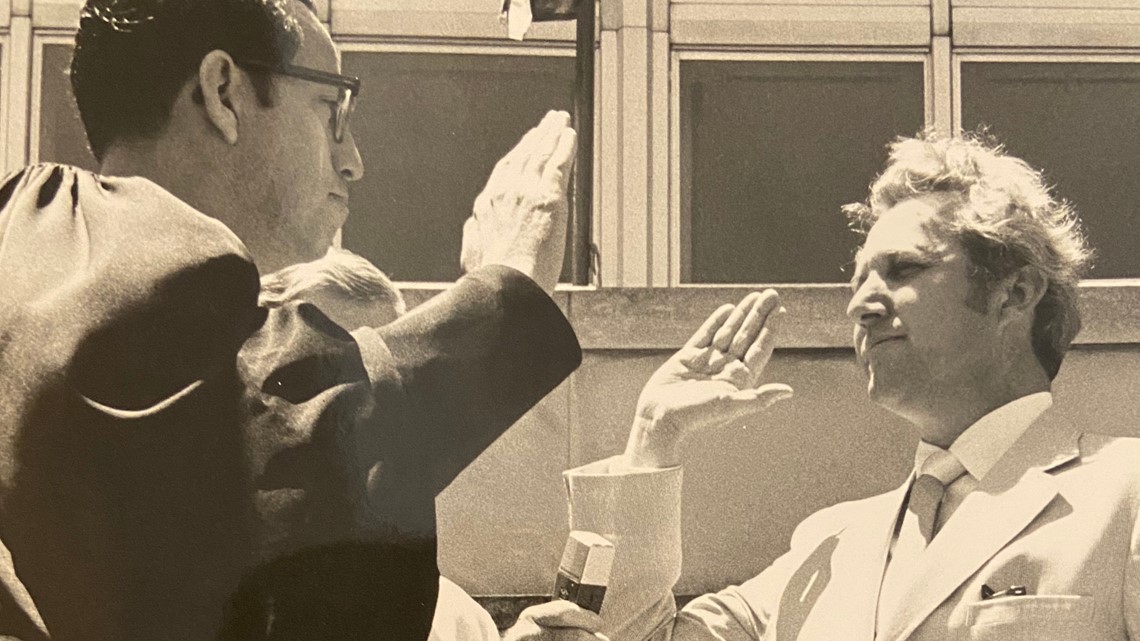

Landrieu was sworn in as the 56th mayor of New Orleans in May 1970, at the dawn of a transformational period for the city. “New Orleans can be a city of hope, a city that illuminates the great opportunities of urban America,” he said in his inaugural address. “It can stand alone among other cities as an example of what can be done by common determination and sincere commitments to defeat the problems that afflict all major cities today.”

In addition to having Black leaders play key roles in his administration, Landrieu was praised for securing federal dollars for the revitalization of the city’s poor neighborhoods and nurturing a growing tourism industry. He redeveloped Poydras Street, helped lead a push to build the Louisiana Superdome, renovated the French Market and Jackson Square and developed the Moonwalk, the French Quarter riverfront park which is named in his honor.

“I think it’s what I know how to do. I think it’s what I do best…it’s where I’m happiest,” he said in 1970 when asked in a WWL-TV interview about his interest in public service. “It’s an extremely exciting life. It can be frustrating, to be sure. But that’s where the action is. It’s where a man can get his teeth into something and fight for it. I’ve enjoyed being in the middle of controversy and trying to make sense come out of that controversy, trying to bring orderliness out of turmoil.”

Maurice Edwin Landrieu was born July 23, 1930 in Uptown New Orleans. He got the nickname Moon as a child.

“His older brother Joseph sort of bequeathed it to him when they were children,” Landrieu’s mother Loretta told The States-Item in 1969. “Joseph had a big face so the boys called him ‘Moon.’” Mrs. Landrieu explained that when Joseph got older, he tired of the name and gave it to his brother, who was often called “Little Moon.”

Maurice legally changed his name to Moon in 1969 when he ran for mayor. “I guess as a kid I didn’t particularly like the name Maurice,” he said. By then a shrewd politician, he also figured more voters would remember the name Moon at the polls, so he made the change official.

The Landrieus were a working class, Roman Catholic family. Landrieu’s father Joseph worked for the city’s transit and utility company, New Orleans Public Service Inc., while his mother Loretta ran a grocery store the family owned on Adams Street. It was a mixed neighborhood of white and Black residents, many of whom patronized the family’s store. Looking back, Landrieu said the situation helped inform his attitudes about race during a segregated time, although he also acknowledged he had no Black friends until he enrolled in college.

Landrieu graduated from Jesuit High School in 1948 and attended Loyola University on a baseball scholarship as a pitcher. He earned a business degree in 1952, planning to become an accountant before switching to a career in law.

Also at Loyola, he met his future wife, Verna Satterlee, who opened his eyes to politics when she served as a student council representative. While courting her, Landrieu would go to student council meetings with her. He later became student council president himself.

Among Landrieu’s classmates at Loyola was Norman Francis, the university’s first Black law school graduate who would later serve 47 years as Xavier University president. During his political career, Landrieu said his friendship with Francis helped shape his views on civil rights, and he often turned to Francis for advice on racial matters. Landrieu later appointed Francis to the city’s Civil Service Commission, where he was the first Black member.

After earning his law degree in 1954, Landrieu entered the U.S. Army as a lieutenant in the Judge Advocate General's Corps. He served for three years before opening his own private law practice above a children’s shop on Broad Street. In 1958, he partnered with friends Charles Kronlage and Pascal Calogero, the latter a fellow Loyola law school graduate who would go on to become Chief Justice of the Louisiana Supreme Court.

Landrieu first got involved in New Orleans politics as a supporter and ally of Mayor deLesseps “Chep” Morrison. Morrison, considered a political reformer, established the Young Crescent City Democratic Association (CCDA) as a way of bringing new faces into local politics in the 1950s. Landrieu worked on Morrison’s failed 1960 campaign for governor and in exchange would receive Morrison’s support in his own bid for political office. Morrison’s endorsement helped, but what actually made the difference in Landrieu’s bid for a state legislative seat was the three months he and Verna spent going door to door courting every potential voter in the Uptown district.

Landrieu served in the Louisiana House of Representatives as the city’s 12th Ward representative from 1960 to 1966. It was a time of intense debate over school desegregation in the state, fueled by the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision calling for public schools to be integrated “with all deliberate speed.”

In his first day on the job, Landrieu ruffled feathers by questioning a pro-segregation resolution proposed by the administration of Gov. Jimmie Davis. Ultimately the measure passed, but Landrieu’s views on integration made him a target for intimidation and threats. "I was prepared to do what was right, but I wasn't prepared to be a dead martyr," Landrieu said in 1996. The task before him, he realized, would be "to try to do what your moral convictions tell you without giving your enemy a chance to defeat you."

Landrieu and a small handful of other pro-desegregation lawmakers were heavily outnumbered by segregationist forces in the Legislature. The pro-segregation majority proposed drastic measures such as ousting the Orleans Parish School Board and usurping its powers to prevent school integration. Landrieu and a small band of like-minded lawmakers voted against that measure and 29 other segregationist bills during a memorable 1960 special legislative session.

As a result, opponents and critics frequently derided Landrieu be calling him “Moon the C--n” – or worse. He received death threats as well, but he stood firm as societal changes slowly took hold in the mid-1960s and ’70s. “Nothing happens overnight,” he said in a 2020 WWL-TV interview with Clancy DuBos. “It’s not a snap of the finger. Things progress with an adjustment here, an adjustment there, and push, push, push. And finally, things work out.”

After two terms in Baton Rouge, Landrieu turned his attention to New Orleans city politics in 1965. He sought and won an at-large seat on the City Council, earning a citywide political base in the process.

One of Landrieu’s first acts on the City Council was to join fellow Councilman Eddie Sapir in calling for removal of the Confederate flag from the Council Chamber. Landrieu also pushed for the creation of a Human Relations Commission, which other cities had implemented as a way to improve race relations.

At the request of the HRC, Landrieu and Councilman Henry Curtis also co-sponsored a public accommodations ordinance in 1969. The measure barred, racial and religious discrimination in local public accommodations. Supporters said such a law had become essential as New Orleans’ convention and tourism industry grew but visitors found themselves discriminated against by local bars and businesses. “If New Orleans is not ready for a public accommodations law, it had better get out of the tourist business,” Landrieu said at the time. “The city must reevaluate itself and decide if it wants to be a great city or if it wants to be a village or town.”

Landrieu also kept his eye focused on the city’s economic development prospects as a member and later executive secretary of the Domed Stadium Commission, a state entity created in 1966 to oversee construction of the Louisiana Superdome, which opened in 1975. Landrieu played a key role in helping arrange financing for the project and was a strong proponent of building it downtown, not in eastern New Orleans as some studies and city leaders had suggested.

“I was not the only one, but I definitely insisted on putting it downtown. It was a bit selfish as a City Councilman. I could see how this would benefit New Orleans by building a downtown stadium and inspiring our downtown to grow,” Landrieu said in 2020. Later, as mayor, Landrieu would further help modernize the city’s downtown by modernizing Poydras Street, which became home to local skyscrapers and the main artery of the city’s business district.

In 1969, Landrieu, then 39, announced he would run for mayor. With Neil Armstrong’s lunar landing coming just months before the primary election, Landrieu called it “the year of the moon.” Branding himself as a fresh voice and reformer – a “man for our time” – his campaign ads asked, “Can a man who tells the truth win?”

Running in a field of 12 candidates, Landrieu placed second in the Democratic primary behind popular former City Councilman Jimmy Fitzmorris. However, a televised debate in the weeks leading up to a December runoff swung the election in Landrieu’s favor.

Both candidates were asked if they would include African-Americans in top positions in City Hall. While Fitzmorris answered that he would “seek out the most qualified people for the job – Black or white,” Landrieu was more definitive, saying he hoped to appoint a Black department head and “perhaps more than one.” His answer was seen as critical to shoring up his support among Black voters, who had become a key part of the electorate.

As a result, Fitzmorris and Landrieu split the white vote but Landrieu earned 88 percent of the Black vote, earning a runoff victory. Landrieu went on to defeat Republican candidate Ben Toledano in the April 1970 general election.

Landrieu kept his word and appointed African-Americans to several key posts, including naming Pete Sanchez as the city’s first Black department head, the Director of Property Management. During his second term, Landrieu appointed Terrence Duvernay as the city’s first Black chief administrative officer.

“I began to search out bright young people, white and Black, and frankly they were not easy to find initially, but I found enough that really gave us some excitement and enthusiasm at City Hall,” he said in a 2009 panel discussion presented by the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities. “I was fortunate in that I was serving at a time when there was a great sense of youthful participation, there was excitement about the civil rights movement.”

Other Landrieu appointees included Robert Tucker, special assistant and later executive assistant to the mayor; Sherman Copelin, Landrieu's Model Cities program chief, who became a powerful state lawmaker; and Sidney Barthelemy, a Landrieu Welfare Department director who was later elected mayor.

“It wasn’t just a question of racial justice,” Landrieu said in 2020. “From a practical standpoint, I recognized – as a politician, as a legislator and councilman – that we were wasting so much talent by precluding Blacks from participation in all matters, government, business and all the important matters of the economics of the city. And I was determined, as I became mayor, to revitalize this city and to bring about racial integration, so that the city could enjoy the full benefit of the white and the Black participants.”

In addition, Landrieu became the first mayor to appoint a woman to lead a city department: Dr. Doris Thompson, who led the City Health Department. At City Hall, she joined Mildred Fossier, the director of the Welfare Department, who was appointed several years earlier by the City Welfare Board.

Landrieu’s time in office was transformational for the city but also marked by tragedies. A tense 1970 standoff with members of the Black Panther party in the Desire public housing development came during the first year of Landrieu’s administration. A Nov. 1972 fire at the Rault Center, a downtown high-rise office and apartment building, killed six people.

In Jan. 1973, the city was stopped in its tracks as sniper Mark Essex fatally shot three police officers and killed and wounded several civilians in a standoff with police and firefighters at the downtown Howard Johnson’s Motor Lodge. After going on an 11-hour shooting rampage, Essex was eventually shot and killed by police.

Just six months later, an arsonist killed 32 people at the UpStairs Lounge, a popular French Quarter gay bar. At the time it was the deadliest attack on members of the LGBTQ community in U.S. history. Landrieu, who was traveling in Europe when the incident happened, was later criticized for his tepid response to the hate crime, refusing to fly home immediately to condemn the act or express public sympathy for the victims.

“It’s one of the regrets I have. I should have found a way to come home immediately,” Landrieu said in 2020. “But in my mind, at the time, the event was over by the time I got home. There would have been nothing there. But I regret that I didn’t get home quicker.”

Despite turbulent times, Landrieu was elected to a second term as mayor. From 1975 to 1976, he also served as president of the United States Conference of Mayors, giving him a national platform from which to advocate for urban issues and the needs of major cities such as New Orleans.

When his mayoral term ended in 1978, he entered the private sector, joining real estate developer Joseph Canizaro's firm. Just a year later, he was picked by President Jimmy Carter to serve as Secretary of Housing and Urban Development. While it put Landrieu on the national stage, he later said he did have some regrets about his time in Washington.

“I often look back and ask myself did I make a mistake because I left a very fine position (with Canizaro) to do it,” he said in 2020. “But I really thought that I could do something for cities across America. I knew what cities needed, what they could do. And I thought I could bring some of that to the national government.”

Landrieu said he felt the slower pace of the federal bureaucracy impacted his ability to get things done: “It’s like operating a huge steam ship in the ocean. You can only change it a little bit at a time.”

When Carter lost re-election to Ronald Reagan, Landrieu returned home to Louisiana and worked in real estate and as an attorney. In 1984, he seriously considered mounting a campaign for president and challenging Reagan’s re-election bid, but later abandoned the idea when he said he saw no path to victory.

In 1991, he ran for and won a seat on the Louisiana 4th Circuit Court of Appeal — the seat once held by former Orleans Parish District Attorney Jim Garrison. Landrieu would go on to serve on the bench for eight years.

By then, several of his children had followed him into public service, including Mitch and Mary, who both won House seats in the state Legislature in the 1980s and ’90s. Although all nine of Landrieu’s children grew up in a politically active household, he said neither he nor their mother pushed any of them into politics.

“Whether you are a dentist, a doctor or a lawyer, a child sees what you do. And some of them take a liking to it and some don’t,” he said. “A couple of mine didn’t take a liking to it, but there were others like Mary and Mitchell who had an automatic attraction to it. Several of the other kids, you couldn’t have begged them to run.”

When asked to reflect on what he was most proud of during his long career in government and public service, Landrieu said his family was at the top of the list.

“My wife and my nine children. I think that’s a very simple answer. I think when I look back at it – and my life generally – I think how lucky I was to find Verna and how blessed we were to have nine good kids and to revel in the births of 37 grandkids and their various careers in law and politics and other areas. I’m a very grateful man.”

Funeral arrangements are pending.