NEW ORLEANS — In 1966 the Black Panther Party for Self Defense came to life in Oakland, California.

Founded by Bobby Seale and Huey Newton in direct response to police brutality. Comprised of mostly young black people, some in their early teens, they spread far, wide and fast.

It was the era of Black Power and Black Liberation -- and The Panthers demanded decent housing, employment opportunities, an end to police brutality and a power to determine the destiny of Black people.

And a right to defend themselves if necessary.

The Panthers' ideals and methods broke away from the Civil Rights era of non-violence, but despite their militancy, they were well received in the Black community. Thanks in part to their free programs and educational classes.

One of those communities was here in Desire, one of America's largest and poorest housing projects.

While the party's efforts to combat poverty and racial injustice made them heroes to some, they became a threat to others — especially the police force.

Fifty years ago, that perceived threat would spread to the city of New Orleans and eventually to a long and violent standoff with police.

So, what brought those young men and women to the Desire Projects leading to the tense standoff that began on Piety Street?

We asked some of the key players to share their recollection of what happened here 50 years ago and the implications it has on New Orleans today.

This is the story behind the standoff.

Before he was an activist, before he was a black panther, Donald Guyton, known today as Malik Rahim, was a soldier who served in the Vietnam War.

“The only thing that was challenging and that was being offered to young black men at that time was the military,” he said. “I was in the Navy during the Watt's riots. I seen what was happening there. I was doing that during the march on Selma.”

It was during his tour in Vietnam that Rahim says his political consciousness awakened. He realized the racism he'd experience in America, he'd also witness overseas.

After an honorable discharge and a hard time finding work in California, Rahim returned to New Orleans.

He looked for work as a welder, but it cost him the work he’d already found.

“I was fired … for asking how to become a welder,” he said. “I was told that they didn’t hire n*****s as welders and I was fired on the spot.”

He was full of rage and had lost hope, but a chance meeting on Canal Street would lead to the beginning of his chapter as the Louisiana Black Panther Party’s Head of Security.

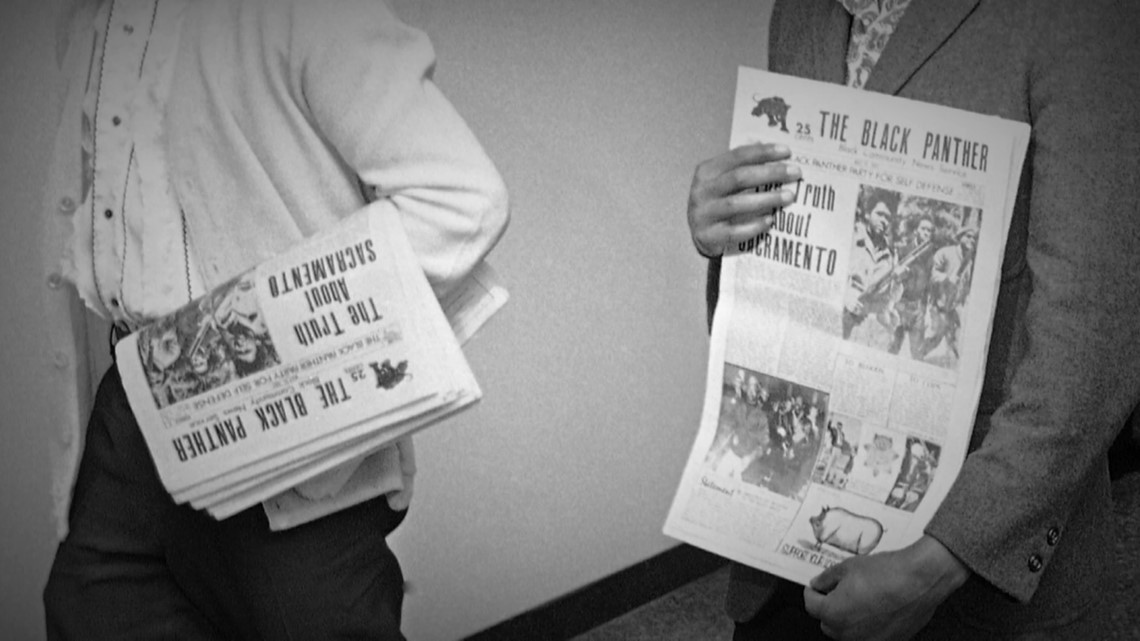

“Brother came up and he had a panther paper and I asked ‘man, where you get this paper from?’ He said, ‘man, there was some brothers on Canal Street selling these papers,’” Rahim remembered. “It was the late Alton Edwards. I bought a paper from him and I told him if he came over to the West Bank, get on the bus right here, come over, get off at the project ask for me and I'll show him around. So, with that, it started.”

May, 1970

“National Committee to Combat Fascism, that's what we started as. It was the umbrella organization under the panthers,” Ronald Ailsworth said.

Ailsworth says he co-founded the chapter here in New Orleans with Steve Green.

Green, also a Vietnam Veteran, was recruited into the Panthers by Geronimo Pratt, a high-ranking member of the party from Morgan City, Louisiana.

“I’m looking for all the dudes who invited me – the militant dudes. I’m a young man, 20-years-old, 21. The rest were older dudes. All of them walked out the door, so I raised my hand and said ‘I’ll join,’” Ailsworth remembered. “I was the first one to officially join.”

Malik Rahim said that you couldn’t just open a chapter of the Black Panthers. You had to work in the community first.

“First you start a National Committee to Combat Fascism. And then through your program, you showed your work within the community,” he said.

Betty Ailsworth, known then as Betty Powell, was curious about the organization forming in New Orleans.

“I just begun to come to the classes on St. Thomas Street and they had what they would call political education classes,” she said. “I kept going to the classes and eventually I'd go around and do a little typing in the daytime and one of the brothers suggested I would be good selling at the papers.”

National Committee to Combat Facism members would sell the Panther Papers on Canal Street. The paper started off as a newsletter in Oakland, California in 1967, but quickly gained major circulation and international readership in just one year.

It talked about issues of police brutality, racial injustice, revolutionary ideals and their community programs. The paper and the image of what a "Panther" was drew members from all over.

But it also drew criticism from the federal government, who saw the black panthers and other black revolutionaries as a threat.

COINTELPRO

Betty, Ronald and Malik joined in the midst of an all-out assault on black political organizations across America.

In the 50s FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover established the Counter Intelligence Program or “COINTELPRO.”

In now released FBI records, COINTELPRO was meant to "expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit or otherwise neutralize the activities of Black Nationalists.

The Black Panther Party were one of their main targets. So much so, that Hoover pledged in 1969 to end the Party's existence.

“They just had a shootout in LA. They had just killed Fred Hampton. Panthers was being arrested everywhere around the country,” Malik said. “When we first came together. We came together, said that, hey, man, we got to stand up, you know?”

“That was a bad group, all they wanted to do was shoot white people and shoot the police,” Betty said. “We never talked about shooting white people. We only talked about self-defense. We did have a lot of white people that did support us, but you wasn't hearing that.”

The intense rhetoric would prove to be challenging for the revolutionaries. Just one month in, the Panther offices near the St. Thomas Housing Project were served eviction papers. One of the lawyers representing them at that time was Ernest Jones.

“They were about to be evicted because the owner of the office was a local criminal court judge, Bernard Bagert, and he had objected to their political education activities in and around the St. Thomas project,” he said.

Jones was fairly new to New Orleans, but not to Louisiana. He grew up in the northern part of the state before taking off for Howard University in Washington DC.

“Howard University Law School was a training ground for black lawyers who wanted to do things in the movement,” he said. “You almost had to.”

So, you could say when it came to taking on the Panther's case, he was made for this.

“We fought the eviction on grounds that the judge shouldn't be evicting them because they were exercising their First Amendment right to organize,” Jones said. “So, we ultimately agreed that they would stay there for a little while and then they would voluntarily vacate.”

But where they would move to next set off a major alarm for the city administration and the police, who had already been alerted the Panthers were in New Orleans and believed with their arrival came trouble.

The National Committee to Combat Fascism

When I asked how the National Committee to Combat Fascism ended up in the Desire Projects, I got a couple of answers. That was actually the case as we dug deeper into this story.

Fifty years later, details can be a little hazy. But we do know the Panthers moved to a building that was here on Piety Street above the Sons of Desire Cultural Center. But, while they were making inroads with the community, city leaders were already plotting their removal.

While the Panthers were settling into the house on Piety Street, Moon Landrieu was settling into his new role as Mayor of New Orleans.

Landrieu, a former state rep and councilman at-large, was a staunch advocate for integration.

He gained a reputation - and enemies - in his fight to socially and politically usher New Orleans into a new era.

“They were leaving New Orleans in the 60s because of the school integration crisis. It multiplied so that many, many whites were leaving the city and going to the suburbs,” Landrieu said. “Our racial attitudes were stagnant. There was a white dominance in the government, a white dominance in business, a white social dominance. And when I became a councilman, I was determined to try to change that world.”

Robert Tucker caught Landrieu’s attention before his race for Mayor.

As tucker recalls, his first encounter, or non-encounter, with Landrieu was during a march to City Hall in 1968 after the assassination of Dr Martin Luther King Jr.

“As the march was leaving to proceed on back to the Urban League office, there was a fella standing in the breezeway between City Hall and Civil District Court,” Tucker remembered. “And I later learned it was Moon Landrieu, didn't speak, didn't say anything. He just watched.”

And what he'd seen was enough to ask Tucker to help him run for Mayor.

“So, there was a debate, a pivotal debate in the 1969-70 mayor race. It was he and the former lieutenant governor. And the question was raised by the moderator, would you be willing to have Black people elected?” Tucker said. “The black community at that point had begun to have some interest in the mayor's race. Because up until then, our political choices or what we've been relegated to was the lesser of two evil whites.”

Moon Landrieu not only won the race, but won with more than 90 percent of the black vote.

“I had no doubt that when I got elected mayor, if I got elected mayor, that I would appoint black department heads along with whites and that I would do this in every area that I could,” Landrieu said.

Tucker was one of those appointments, brought on as one of Moon's three executive assistants, making him one of the first influential black men in city government.

The political landscape was changing.

“At the same time, you had black militants. There were riots taking place all over the United States. We didn't have one here. But then the Panthers came here and they were very militant group,” Landrieu said.

But what did he know about them at the time?

“The only thing I knew is that I'd heard they were in California. And I think they'd gone to Philadelphia and someplace else. I just I just knew them to be a very militant, aggressive group of Blacks who were seeking -- I don't know what the ultimate goal was,” Landrieu said. “Maybe it was separation. I don't know. But it certainly was against racial injustice.”

It would be one of the first major challenges for the Landrieu administration.

The Desire Projects

Black revolutionaries were under fire.

By 1970, Black Panther chapters across America were in shootouts with police. Members were arrested and jailed on a number of charges and had developed, at least among most whites, a reputation for violence.

With that in mind, city government and police officials were quickly on alert.

“I could not accommodate what they were trying to do here,” Landrieu said.

But the New Orleans Chapter hadn't threatened any violence up until that point. Instead, they did the opposite while in the Desire Projects.

“The first thing is how to restore hope. How to make people believe that, hey, you ain't going to have to take the abuse and oppression of racism all your life and then die,” Rahim said.

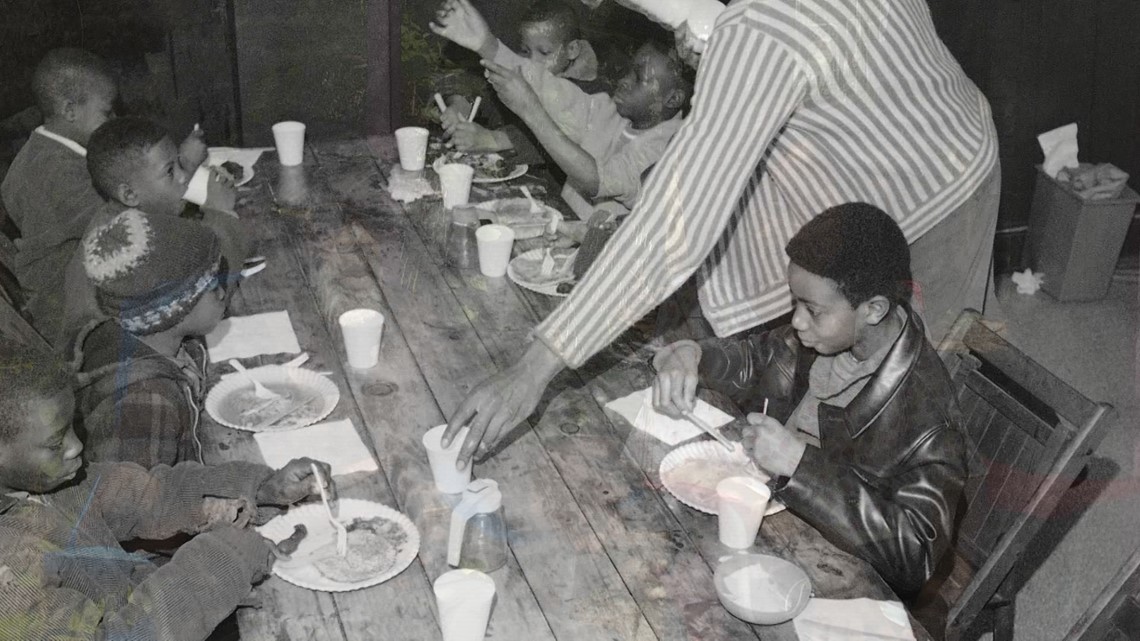

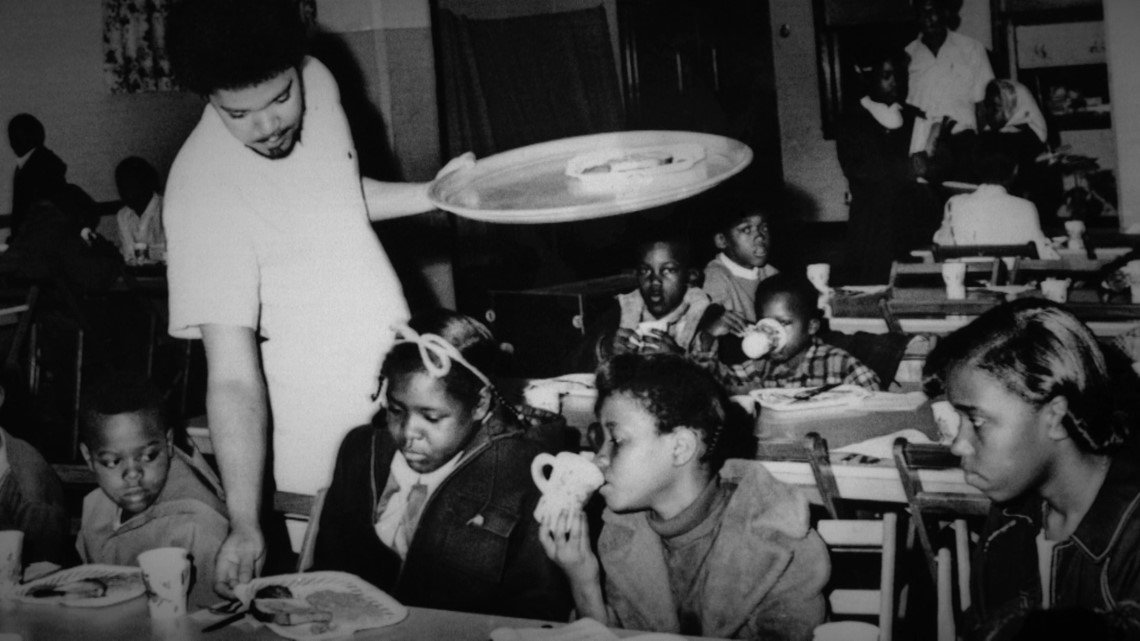

They worked out of the community center and closely with the center's director, Johnny Jackson, to operate the Panther feeding program.

“Because a child cannot go to school and really learn anything if they're sitting in a classroom hungry,” Betty Ailsworth said.

“We didn't go around carrying big guns. No, we did party work, clinic work, sickle cell anemia. They don't highlight that. They highlight confrontation,” Ronald Ailsworth said.

“We bused people to the prison. We bused them to the election when Johnny was running. We made groceries for people on buses when people weren't able to go, like the seniors and stuff. We went and cleaned their houses. We helped them out,” Betty Ailsworth said.

“We went in our community and started offering programs to assist them. Never asked for a grant,” Rahim said.

“We were really young anywhere from 14-to-21, something like that,” Betty Ailsworth said. “What we did was a sacrifice of love. We didn't know what we were doing. We just saw a need and we jumped in.”

“They painted us like a villain and a threat, we was the best thing the community ever had,” Ronald Ailsworth said.

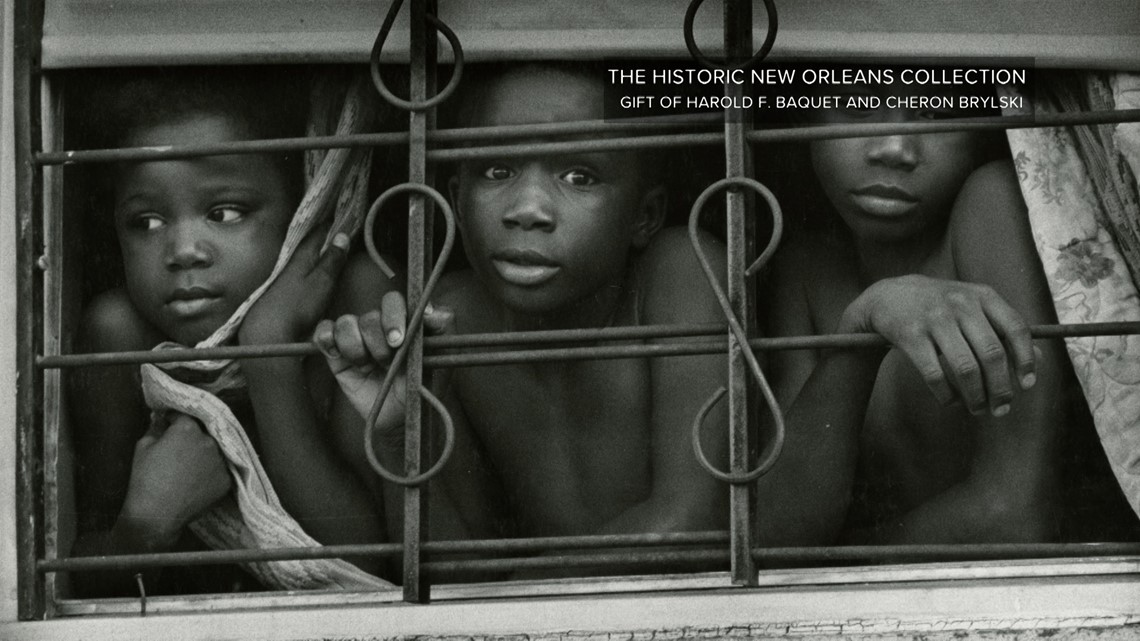

In 1970, the Panthers and the city government described Desire as undesirable.

“It was one of the most down and deprived areas where African Americans were at. They needed our assistance where we could give it to them,” Betty Ailsworth said.

“Deplorable. The murder rate -- everything. But we got down there we brought the crime rate and murder rate down,” Ronald Ailsworth said. “We started running the big time dope dealers out of there.”

“We went through Desire and anybody who lived through that period can attest to this: The safest time in their history of being in that project was when we was there,” Rahim said.

Bob Tucker says he was also concerned with Desire's crime rate and condition.

“After we were elected and looking over the city and seeing where the what was going on. One of the things that I came up with was desire,” he said. “High crime, crime rate. Nothing about the Panthers at that point, but just a poorly constructed housing development. And I got curious about it and embedded in Desire after I met a guy named Henry Fagan … (Henry) just was the mayor of Desire. And so he helped me to understand what and how bad it was.”

Tucker did a study on the large community and reported back to the mayor.

Desire Housing Projects were built in 1956 to house large black families. That same year, a tenant's association told the Times-Picayune the Desire was "Unsafe for human habitation," calling the project “a real scandal and a blight on public housing in New Orleans."

Even before Desire opened itself to tenants, the infrastructure was crumbling.

“The desire project was a mistake from the start,” Landrieu said. “It was built on a dump. It was poorly constructed. The place constantly flooded. And it was it was just too large.”

“There was no cement under the floors of the structures so that you are literally walking on soil,” Tucker said. “It was built that way because that was the intent. It was the Black development … So it was destined for failure. But because there was no other housing at that point in that area for blacks became occupied.”

In 1971, Johnny Jackson told the Times-Picayune "12,000 people lived in Desire and about 8,000 of them are under 18-years old."

Geographically cut off from the rest of the city, Desire residents sat isolated in the Ninth Ward.

So you would understand why the Panther's would be such a force in a community that was over populated and underserved. It followed a common theme with the Black Panthers.

Chapters across the country set up in neighborhoods just like Desire. Mostly minority, mostly poor, most in living conditions that were deemed blighted or uninhabitable.

“I think the Panthers made a big difference in the community and I don't think people gave them the credit that they rightfully deserve for doing what they did at the time they did it,” Leonard Smith III said.

Leonard Smith III, Pamela Devezin-Everage and Larry Everage Sr. all grew up in Desire and they remember the Panthers very well.

“They implemented the breakfast program. I used to go over to get books. They had really good books,” Pamela Devezin-Everage said.

“I worked with the breakfast program,” Larry Everage Sr. said. “We just set up, like our children, milk and meals before they went to school, especially from kindergarten to third grade.”

Larry noted that it wasn’t just what the Panthers were doing that drew people to them, but what they were stopping. Specifically: Drugs.

“Yeah, they stopped it, actually,” Pamela said. “At that time, put a stop to it. And they actually used to patrol. They used to do morning patrol, evening patrol.”

“Well, this was the era of being black and proud. James Brown and all that had come out, you know, and so it was actually kind of like almost an honor for them to be in our community,” Smith said. “I think that because of the influences from the media made it seem like they were doing such horrible things. But they really were a positive role model.”

While all three admit some of the stories about the living conditions of the Desire are very true, their memories growing up in the community are vastly different than the conditions described by the city and the Panthers.

“Growing up, it was actually really nice,” Pamela said. “It was like Desire was like a city within a city. We had our own show. We had a bowling alley. We had neighborhood drug stores inside the community.”

Stories of violence and drugs would paint a picture of Desire that forced outsiders to fear the community. But if you spoke to those living within the confines of Desire, they'd share stories of thousands of children skating on Christmas Day, turkey bowls, football games and sewing at the neighborhood community center.

Desire residents would say they were playing the best game they could, with the cards they were dealt.

Leonard talks about this in his award-winning documentary, "A Place Called Desire."

“They had about five or six stores. It was black-owned stores and then they had entrepreneurs in the community,” he said. “We were in this little bubble, more or less, but there was a lot of activities. And we made our own activity, you know, because the city was kind of looking the other way when it came time to talk stuff that the community needed.”

So when the City wasn’t taking care of Desire, Desire was taking care of itself.

NOPD Infiltrates the Black Panthers

By 1968, The Black Panther Party had chapters across America and their membership had grown to the thousands. But among the influx of members were infiltrators, placed by federal and local government

“One day we were told by our supervisor that the Black Panther Party now has a presence in a desire project,” Larry Preston Williams said. “And that raised some eyebrows because we're thinking that that's a predominantly black housing development and they can recruit.”

Williams was an NOPD officer who worked to infiltrate groups as part of the departments Intelligence Division.

“My job was to infiltrate radical organizations and do surveillance,” he said. “At that time, Panthers and the Panther operation was high priority to infiltrate and keep a watch on. Mainly because the Panther Party nationally had a reputation for confronting police officers.”

So, why put their full attention on the Panther Party, as opposed to a group like the Ku Klux Klan, who are known for committing hate crimes? Williams said it simply: “I’m working for a police department and the Ku Klux Klan don’t attack policemen.”

“The police department here was more was less concerned about the Black community as a whole, more concerned about the police department,” he said. “In other words, if there was a group that's likely to attack police officers that got our undivided attention.”

Williams was a police officer who had to face two fronts, being both Black and blue, leaving him conflicted over the Panthers arrival.

“I understood their program, free breakfast in a poor neighborhood. They were concerned about health care. They had a program that consisted of probably, if I remember, eight or 10 points. You could not argue with the eight or 10 points,” he said. “What I had to argue with was their tendency or their rhetoric about shooting police officers because they felt that police officers was an extension of white society and was racist, and that in order to protect the black community, that one time at some time they would have to confront police officers on the streets.”

And that confrontation, the first one at least, would come sooner rather than later.

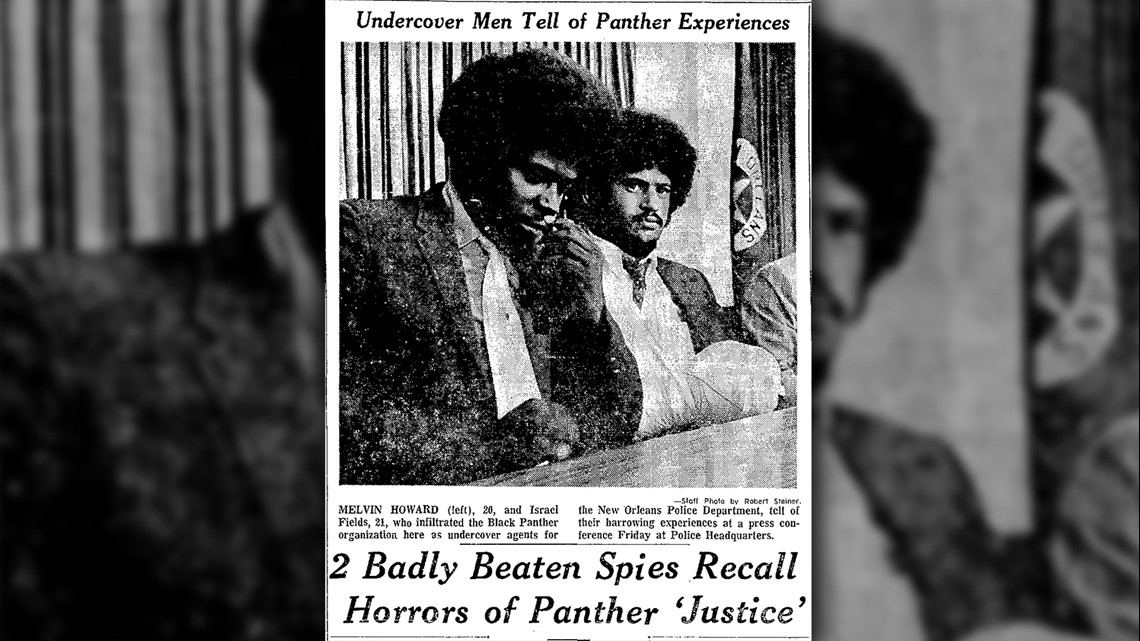

The Panther's had been infiltrated by two undercover officers, Melvin Howard and Israel Fields. But according to the Panthers, their infiltrators were outed long before initial confrontation with police.

“Most of us knew that they was police,” Rahim said. “If they wasn't police we know that they was snitches or rats … we knew that this was the tactic that was being used around the country.”

Rahim said their suspicions were confirmed when two kids saw the undercover officers in uniform at Tulane and Broad.

“By then, the tactics was already set. So, let's just use them. Let's just keep ‘em around,” he said.

But they wouldn't stay around for long.

The People's Trial

The Panthers held what they called a "People's Trial" and the suspects being tried were the two NOPD officers who, unsuccessfully, went undercover.

“I made the mistake of telling them that Fields and Howard was police,” Rahim said. “It was exposed. You know, that we had two police in our midst.”

“They let them out the door and the people had them,” Ronald Ailsworth said. “Melvin Howard jumped over the rail and got away, but Israel Fields the people caught him in the street and beat him. He ended up running into the pharmacist store and they came and got him out of there.”

Israel Fields has since passed away and Melvin Howard, who is still in law enforcement, couldn't be reached for this report.

This is Fields account of what happened during the People's Trial:

Betty Ailsworth said no Panthers touched them, they just gave them over to the public.

Just days before Fields and Howard were outed, the Landrieu administration met with the newly appointed police chief Clarence Giarusso after Clarence Broussard, a neighborhood grocer and owner of the building the Panthers were currently occupying, moved to have them evicted.

“And the black owner came to me and told me these people are occupying his house. And I said, OK, I know what you want,” Landrieu said. “So, I told him to go get an eviction notice from the court, which he did. I saw that the eviction notice was enforced and sent to police with the deputy of the clerk to drop it off. They wouldn’t open the door they dropped it on the steps.”

Tension was mounting.

“I got a call that night from a member of the party, who said we will be in some trouble,” Jones remembered. “We found out about undercover agents and the cops were going to vamp. That was the lingo of the time.”

Vamp, meaning they were going to pull off an early morning raid. One where people were always arrested, sometimes killed.

“The Black Panther Party was named the Black Panther Party for self-defense. And one of the party principles that we understood perfectly was that they would defend themselves if attacked,” Jones said. “And so they were prepared to do that.”

September 15, 1970

The Desire Projects once isolated and ignored had suddenly found themselves in the national spotlight.

Sixteen Panthers were now arrested, 12 of them charged with five murder attempts after a 30-minute shootout with police.

While at Orleans Parish Prison, Ronald's fingerprints matched a bank robbery that happened on Jefferson Avenue. He would soon be sent to Angola State Penitentiary.

Ronald told us he robbed the bank to cover Panther expenses.

“Not everybody in the party was doing that,” he said. “We had a party of workers who were making money.”

For the other Panthers, bail had been set at $100,000 each.

“The judge who set the bail turned out to be Bernard Baggertt, the same judge who had gone through the eviction process with them before,” Ernest Jones said. A clear conflict of interest.

The case had been allotted to Judge Israel Augustine.

“The only black judge at criminal court. How did that happen? Just by random accident? Well, I'll let you be the judge,” Jones said.

In the meantime, Desire leaders expressed their disapproval of how the city handled the confrontation and the reason behind it all.

During a press conference the day after the shooting, they cited the violent outbreak as the result of the city turning its back on a community that desperately needed its attention.

“We went right back the next day and reopened the office and started again,” Betty Ailsworth said.

The remaining NCCF members who had left the Piety Street house before the shootout had taken up inside of an abandoned apartment on Desire Parkway, right next to the community center.

There, they could continue their free community programs.

But the fact of the matter was, they were still in Desire and the city still wanted them out.

“We have a staff meeting at three in the morning saying that the police were getting ready to go down to Desire the Desire Housing Project to evict the members of the Black Panther Party that were illegally occupying the desire housing project,” Bob Tucker said. “It was suggested that I go with the mayor to help logistically bring the kids -- I call them kids they were young folks out of the panthers -- out of Desire. I told the Mayor that was not going to work.”

Why did he say it wouldn’t work, though?

“Because I was a Black man. And you asking me to go about myself in possibly bringing death to those folks because it was understood that the cops were going to be coming out in large numbers,” he said. “So I walked out of our office, headed down to desire, picked up guys who had been working down there … Cecil Carter, Don Hubbard. Charlie Elloie …. Our attempt was to begin to negotiate with the Panthers because we had the credits … and what they explained to us was that we got to do what we got to do.”

November 19, 1970

A second standoff was looming.

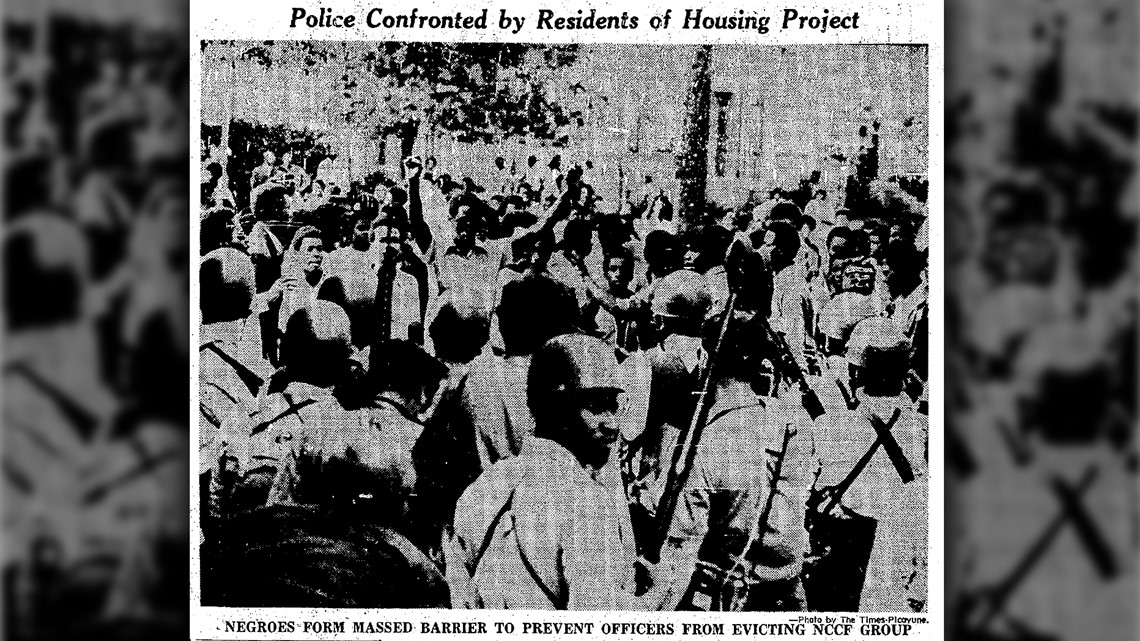

This time, 250 police officers assembled and marched into the Desire Projects turning the large community into a battlefield.

“There was nothing about that confrontation that reeked of de-escalation,” Larry Preston Williams said. “NOPD went bananas.”

“They came with blood in their eyes. They wanted to kill something,” Better Ailsworth said. “They wanted us out. They wanted to evict us. So they came down with a little army tank against a bunch of teenagers.”

But as the army of police officers, tank in tow, prepared for a second showdown with the Panthers, so did the Desire community. And this time, they weren't just standing by.

“The word got around of the police coming out with a little tank. So, everybody was saying with a tank, not here. Not here,” Larry Preston Williams said. “So people just started coming out.”

“People refused to leave because they said, we leave you, y’all gone kill these boys,” Pamela Everage said. “And they say, no, you can't kill them. You're not going to kill them. We're not going to let this happen.”

“You got like, over 400 people moving, like 400 like teenagers and stuff. The police saw that, they were shocked because of the crowd,” Larry Preston Williams said. “So we had the tank surrounded to wedge between the panthers and the police. And we encircle them, so the thing is, we are in a standoff.”

“The people saw what was going on and they came out in the masses and supported us and you know they just wasn't letting it go down,” Betty Ailsworth said. “They were chanting and everything … Power to the people. Get those pigs out of here.”

“I don't think Clairence Giarusso, who was chief at the time, wanted a real confrontation, a real shootout,” Larry Preston Williams said

“So, we were talking using a conventional phone, talking with the mayor at police headquarters, going back and forth. And the bottom line was that we had begun to understand how serious it was,” Bob Tucker remembered. “It was suggested to the mayor that you've got to pull the cops out.”

In attempt to avoid bloodshed, Desire residents used themselves as a shield to protect the Panthers who'd they now seen as allies in their struggle. Landrieu ordered the police to pull out.

“The police department, of course, wouldn't shoot a group of people standing between the target and the police department,” Larry Preston Williams said.

“The people's position, was that when we want the cops we can't get them. The system doesn't handle any of these issues,” Bob Tucker said. “There was no assistance from the system. But on the other hand, because the Panthers had made both an operational and a political statement about how bad it was. Now all the attention was focused on Desire.”

The attention was now focused on the plight of Desire.

The NOPD and city administration made national headlines after the violent shootout with the NCCF.

It even brought actress and activist Jane Fonda to the Desire neighborhood

"How can we, smug white people, say what they should do? We have done nothing to stop the violence against these people," Fonda said. "We're having a demonstration in front of the housing authority office to demonstrate support for the NCCF and to demand that they allow the NCCF people to live in their community."

The NOPD would use her visit to make one more effort to remove the NCCF for good.

November 25, 1970

Jane Fonda rented four cars to transport some of the members of the NCCF and their supporters to the Revolutionary People's Constitutional Convention in Washington D.C.

But they wouldn't make it passed state lines.

"They were on the way to that rally police caught them on the interstate and arrested them," Ronald Ailsworth said.

Betty Ailsworth was with the remaining members inside the apartment on Desire Parkway.

"That night they had another sister and I was talking to them about getting them out of jail," she said. "I happened to look out the window and I saw this mail truck about 1 o'clock in the morning ... There was a knock at the door and another sister opened it, thought it was the priest, but the police had come dressed as a priest and the police pulled her out and they came in shooting."

Betty was one of the people shot that night. The buckshot went through her breast and came out of her arm. She still has five pellets in her body today.

The National Committee to Combat Fascism would spend the next 11 months behind bars awaiting trial.

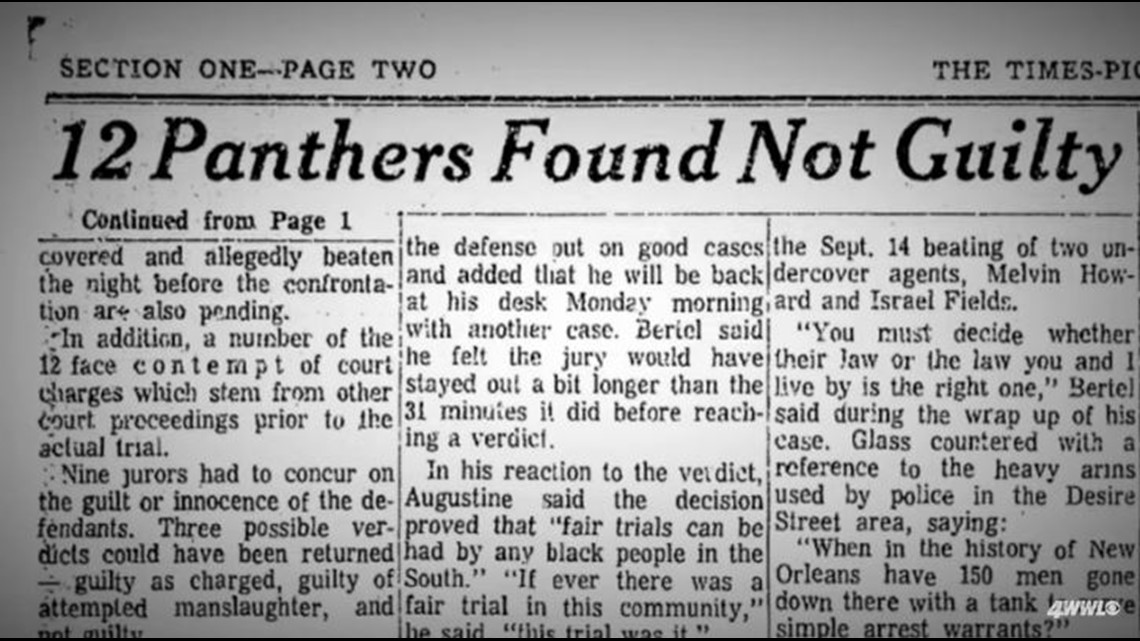

"Part of the the Panther programs, part of the ten point program was that black people should be tried by a jury of their peers," Ernest Jones said. "I contacted Charles Gary, who was Huey Newton's lawyer in Oakland and asked for help and Gary sent me a pamphlet done by a colleague of his called Minimizing Racism in Jury Trials. That pamphlet became my Bible."

The law in Louisiana at the time allowed criminal defendents 12 peremptory challenges, letting them take somebody off the jury for no reason at all. With 12 defendents, Ernest Jones had 144 peremptory challenges.

"The jury selection took over a month," he said. "The trial only took a week."

The NCCF members arrested for the Sept. 15 shootout with police would be found not guilty on all charges.

It was the first Black Panther trial in the country to be tried by a black judge and a majority black jury.

"Desire is a page of New Orleans history that's been left out"

In 1970, the city of New Orleans successfully stopped the Black Panther Party from maintaining a foothold in the Desire community. But some would say they failed to address why the Panther's were needed in the first place.

What could have been an opportunity to change the outcome of those living in Desire was instead met with misunderstanding and fierce resistance of who the Panther's were and what they stood for.

We asked Moon Landrieu if he could go back and do things differently, would he?

"Well, if I if I could think about it, I could probably come up with some individual areas that I would redo in a different way," he said. "I was determined to integrate the city in a business way and a social way and a political way so that everybody had equal opportunities ... And I think while I may not have achieved that perfectly, I think we made great progress."

The Hope Six grant led to demolition of housing projects across the city. Today, there is nothing to remember what happened here on Piety Street. Instead, its now a mixed income community called The Estates.

"All of the housing developments throughout the city was able to have one building left to replicate what it was before Katrina. Right. Well, they didn't do it, for desire," Leonard Smith III said.

But what does remain is the ongoing battle against social injustice in America.

"It's ironic that its happening again, 50 years later," Malik Rahim said. "They had their feet on our neck then And they have their feet on our neck right now."

Fifty years ago, a new wave of activist would define a decade in the war against systemic racism and segregationist policies.

Fifty years later, a shattered country began to piece itself together and those who were left with no hope somehow found hope again.

And that battle waged on.

RELATED: 'I want it to end here' | McDonogh 3 turning school they desegregated into Civil Rights center

► Get breaking news from your neighborhood delivered directly to you by downloading the new FREE WWL-TV News app now in the IOS App Store or Google Play.