NEW ORLEANS — In August, the century-old Market Street Power Plant, with its Dickensian smokestacks looming over a structure that has been decaying since it was abandoned five decades ago by Entergy, was the site of the tragic death of teenager Anthony Clawson when he fell 50 feet to his death while exploring the building.

Earlier in the summer, the abandoned 25-acre Naval base at the intersection of Dauphine Street and Poland Avenue in the Bywater section crashed into the headlines when it became a source of soaring local crime. Built-in 1919 as a supply depot, it has sat empty and unused since the Pentagon "disestablished" it in 2009. It has gone through several failed attempts to rehabilitate it as disaster management center or mixed-use neighborhood. In July, police swept the site to remove dozens of squatters after a series of shootings at the site left one person dead.

The Plaza Tower has been troublesome since it was built in the 1960s and has sat unused and deteriorating since the last office tenant left 20 years ago. Various owners have struggled to keep out trespassers and the city was reminded of the skyscraper's hazards last year when high winds blew debris off its upper levels hitting a passing cyclist.

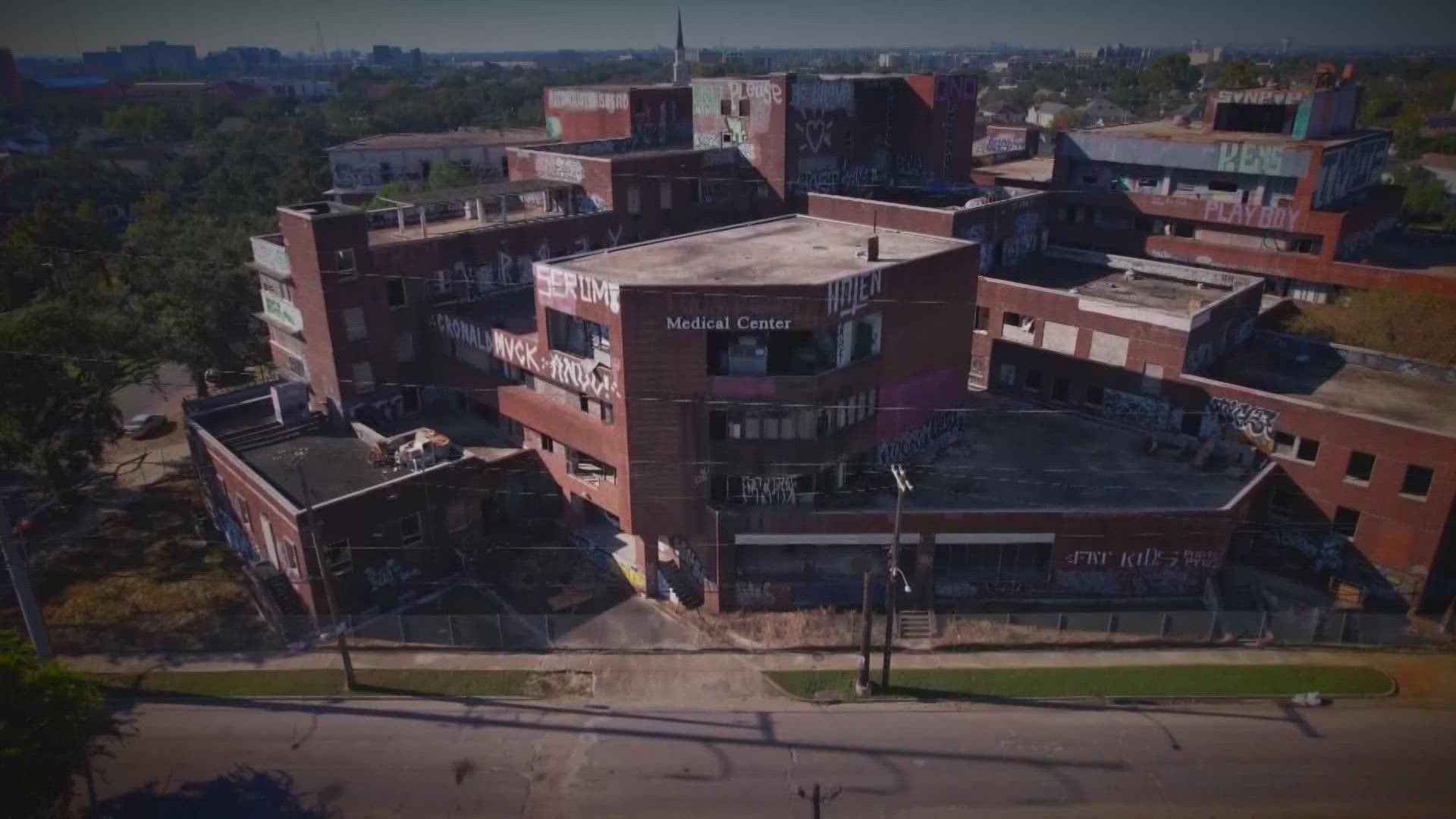

In Mid-City, the old Mercy Hospital on Bienville Street (the Boggs family asked the new owners to remove the Lindy Boggs Medical Center signage) has been a favorite target for vandals and graffiti "artists" as it has sat unused and uninhabited since Hurricane Katrina. On a recent Friday night, trespassers could be seen wandering its roof wearing what appeared to be spelunker headlamps.

Joe Jaeger, one of the city's most prominent developers and hotel owners, has at one time or another owned all of the properties on that list. He says there's not much private developers can do to keep the trespassers out and secure the sites.

"We'll go and put gates and chains and whatever," Jaeger said. "You can't call the police; they have more important things to do. Between professional strippers who strip the building and the vagrants that are doing whatever, and the thrill seekers, you can't police it. We just do the best we can."

Jaeger and other developers typically take on these projects after they've already been deteriorating for years. Turning them around hinges on securing finance, which usually means lining up government subsidies to make the deals work.

Mayor LaToya Cantrell last month acknowledged that the Naval complex project was contingent on financing from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, which she said her administration is pushing for.

"HUD is a large component that's tied to the (Naval) site," she said. "Those projects are so large and you need a multifaceted approach to attack them and bring them back into commerce...The City is putting support at every single level, at the federal level."

Cantrell also acknowledged that City Hall has a role in securing the property while financing is in the works. "Because it's costing us an arm and the leg. I mean Joe, we're pushing him to pay for security and all but it is still costing us because we have to respond. We have to clean it up. We have to put the fires out. We have to ramp up our operations to move people out. It's a problem."

After the July sweep of the Bywater Navy complex, Jaeger told a neighborhood meeting that the plan to turn that site into "luxury" affordable housing is still unclear. Lengthy negotiations with the federal Housing and Urban Development agency had been set back further by the recent crime problems.

Another of the city's prominent developers, Paul Flower, says he feels Jaeger's pain.

"It's difficult in New Orleans because you almost always need subsidy because of all of the issues we have here," he said, referring amongst other things to the city's high crime rates, declining population, and the costs of insuring in a hurricane and flood-prone zone.

Flower's company, Woodward Design+Build, bought the old Mercy Hospital from Jaeger in early 2021 and he, too, has faced delays in securing financing from HUD for a project to convert the site into a "continuing care" facility. "Almost every developer is looking for some sort of federal assistance, a federal program, especially for a project like this," Flower said. He is now hoping to start construction sometime next year.

But what responsibility do developers have while they're waiting, maybe for many years, for their deals to come together?

Joe Brown, a Neighbors First For Bywater board member, said after the police-led clear out of the Naval complex in July that action was long overdue. "Enough is enough,” Brown said. “If the people who live (in Bywater) have to deal with it, I can tell you it won’t be pretty.”

Val Walker, mother of 18-year-old Anthony Clawson, went to see the Market Street Power Plant property three days after her son fell to his death there.

"This gate right here was wide open and this door was wide open and the another door down here was wide open," she said, pointing to easy points of access to the site. "So, it was very easy for them to enter the property."

She said the power plant, like other such sites in the city, is well known among young people for its "urban exploration" — or urbex— potential, and young thrill seekers posted videos of their exploits on YouTube. The dangers were well known and the owners and City officials should have been more vigilant, she feels.

"They have the authority, but they won't take the responsibility," Walker said.

John Lawson, a spokesman for City Hall, said the new owners, led by local developers Louis Lauricella and Brian Gibbs, have beefed up security precautions.

"The current owners have been in constant communication with the City regarding trespassing issues at the site," Lawson said via email. "They have taken substantial steps to clear and secure the site with an electronic perimeter fence and VPS gate system over every lower-level opening on the structure."

A spokesman for the power plant owners said they're trying to speed along development of the site, which is the surest way to keep it secure.

"Their very motivation in buying the Market Street Power Plant was to renovate and transform a historic building in our city into an entertainment complex that our entire community can be proud of," said Peter Aamodt via email. "That motivation remains today.”

Aimee Adatto Freeman has made property code violations a central issue since she was elected to the Louisiana House of Representatives for the New Orleans District 98 in 2019. She has tried unsuccessfully to pass legislation that would increase vigilance and fines for developers and property owners.

Freeman said she's frustrated by the lack of action to enforce the codes to their fullest extent now, even before toughening up the penalties.

"At what point are you just going say, 'we really care about the safety of not having someone die on a property because it was blighted and left behind and dangerous?'" she said.

Jaeger, who Lawson said had been fined more than $6,000 for code violations at the power plant in 2019, noted that he did not own it when Clawson fell to his death. But what if a teenager fell from, say, Plaza Tower while they were thrill-seeking there?

"I'm not sure, because if I weld the doors up and somebody comes and cuts the door and gets in there and does whatever, how can I stop that?" Jaeger said. At the Navy property, trespassers did just that: they brought their own welding equipment to open up doors that had been welded shut.

One thing the developers and the City authorities agree on is that the best outcome is speed along the development of these projects.

Reed Wiley, a commercial real estate broker at Latter & Blum, said that some other major cities have taken a more proactive "carrot and stick" approach to developments, whereby there are both incentives in place to encourage moving the projects along quickly as well as tougher fines for delays or blight.

"The city also needs to work with those owners to find solutions, because some of these assets are large, they're massive, and I think securing sites are tricky. It's not a perfect system," he said.

Flower, the developer who completed the conversion of the World Trade Center into a Four Seasons Hotel and Residences last summer after years of delays, concurs that fines alone won't solve New Orleans' blighted property issue and could make it worse by scaring off the few who might eventually be able to get the projects done.

"If I knew I had, along with all the other costs that we're having on (Mercy Hospital), to have to be paying fines along the way, then I wouldn't have gotten involved in it," he said.