NEW ORLEANS — Boo Williams wakes up each morning not knowing how the pain will hit. It could be debilitating headaches that make it impossible to get out of bed. Sometimes the pain shoots down his neck. Through all of it, he’s angry.

Williams, who played tight end for the Saints from 2001-05, needs surgery, medicine and doctors, but struggles to afford any of it. The 44-year-old, who lives in Picayune, Mississippi, was recently awarded $5,000 a month by the NFL’s disability benefit plan, but says the plan and the league have repeatedly mishandled his claims and should have paid him $500,000 or more over the past 14 years.

“I need all the help I can get because, some days, it feels like it’s going to be all over,” he told The Associated Press. “Sometimes I can’t sleep. It all makes it harder when you’re fighting to get what you deserve and all you do is get frustrated.”

His story is not unlike dozens of retired players in similar positions who spend their days picking through a web of lawyers, paperwork and bureaucracy in a fight against the NFL and its NFL Player Disability & Neurocognitive Benefit Plan.

Over the past 30 years, the league has added millions of dollars to the plan for retired players with injuries they suffered playing football or that emerged after their careers were over. Approved as part of the collective-bargaining agreements between the league and players union, the plan expects to pay more than $330 million in benefits in 2023, NFL spokesperson Brian McCarthy said.

But plaintiffs’ lawyers point to a high rate of claim denials and a system in which doctors assigned to examine players are paid by the NFL plan as evidence the system is rigged against retirees.

Earlier this year, 10 players, including retired Pro Bowl running back Willis McGahee, filed a lawsuit accusing the program of unfairly denying benefits to injured retirees.

“After years of putting their bodies on the line with the NFL’s promise of assistance should they need it, former players are met with an unfair and biased system for obtaining their rightful benefits,” said Sam Katz, an attorney representing players in the lawsuit.

Williams, who was first signed as an undrafted rookie for a salary of about $200,000 and made a total of about $2 million over his career, never sought the top award.

His journey through the claims system began in 2009 when he sought benefits under the league’s “line of duty” disability policy for active and recently retired players who suffer football-related injuries.

All signs pointed toward him receiving payments of around $2,400 a month, after an orthopedic doctor assigned by the plan evaluated Williams. Dr. George Canizares graded Williams’ “whole person impairment,” or WPI, — a gauge of the severity of his injuries measured by standards set by the American Medical Association — at 27%. Rules at the time said if a player was rated 25% or higher he could receive benefits.

But three weeks after Canizares filed his report, he sent an addendum downgrading the severity of one of Williams’ injuries, to his left shoulder, at “the suggestion” of NFL Disability Plan Director Dr. Stephen Haas.

Crossed out was the “27” in the spot labeled “Combined WPI% Impairment.” Next to it, “24” was handwritten and circled.

It would take another 14 years for Williams to get approved for benefits.

“That’s what led to a lot of my depression,” Williams said. “I couldn’t get any help. I didn’t see how a guy who wasn’t in the office could tell the doctor to change the number like that.”

Neither Canizares nor Haas responded to messages for comment left by the AP.

NFL spokesperson McCarthy said the NFL and the union's “jointly developed and administered program led by neutral medical personnel fairly delivers benefits to deserving players and their families.”

However, lawyers representing Pro-Bowl player McGahee and others said an examination of 784 medical evaluations, most from the last five to seven years, exposed a relationship between how much doctors were paid and the number of denials they issued.

“There is a clear pattern that shows the more the board pays a doctor, the higher that doctor’s rate is of denying former players their benefits,” Katz said.

Additionally, the attorneys found regrading of injury severity, as happened in Williams' case, is not uncommon.

The NFL says there is no link between the amount doctors are paid and their denial rate. The league did not respond to questions about regrading injuries or the specifics of how Williams' case was altered.

“Physicians are selected by the parties,” McCarthy said, referring to NFL management and the union. “They are vetted through a panel of NFL and (benefit plan personnel) and undergo orientation, training and ongoing education about our disability plans.”

Williams has received about $45,000 since being approved earlier this year. It has allowed him to rent a house, but he still has no car and says he can’t afford the medical care he needs for his neck injury.

“There are times when I call him early in the morning, and his head is throbbing so bad, he wants to go out somewhere and kill himself,” said his friend George Hawthorne, who is helping Williams navigate the benefits process. “I’ve had to talk him off the ledge many times.”

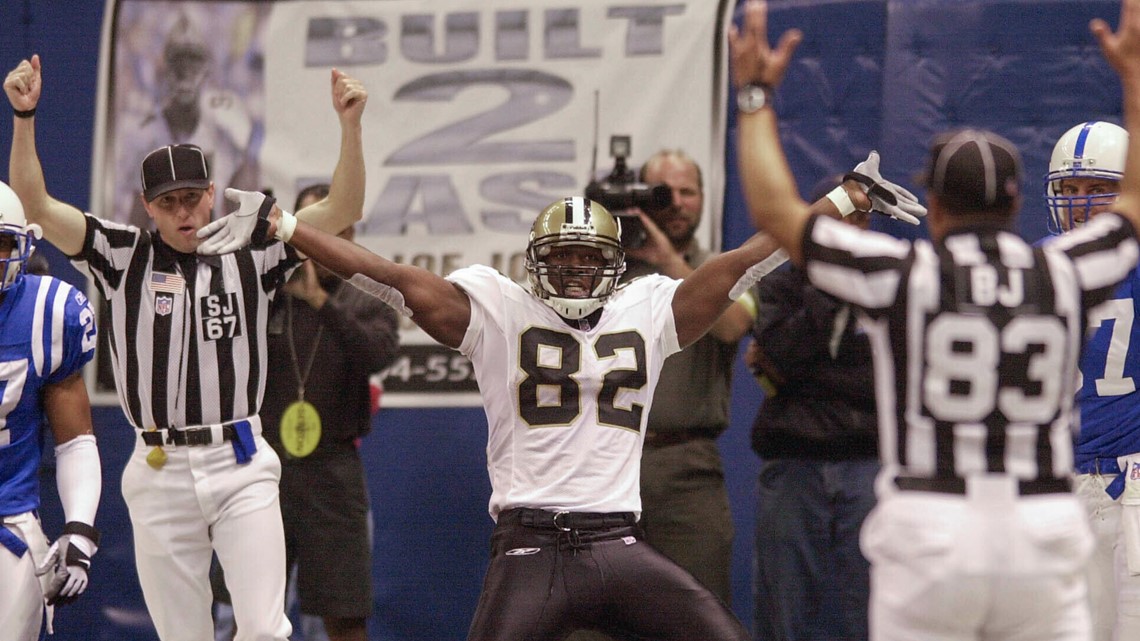

And yet, this is not the worst it's been for Williams, who amassed 107 catches for 1,142 yards and 12 touchdowns over his four seasons in New Orleans, but whose NFL career ground to a halt about five months after he suffered a knee injury in a 2005 preseason game.

He reached a low point in 2011, when he laid down on railroad tracks not far from the Saints training facility in Metairie, Louisiana. Two homeless people pulled him to safety. Williams entered rehab at the Crosby Center in San Diego. He said his experience there and the help of medical marijuana have kept him alive for the past decade-plus.

“Thanks to San Diego, I was able to stay sane and get a good reminder of who my friends were,” he said. “They were in my corner, telling me not to give up.”

NFL health insurance for retired players ends after five years, so Williams' benefits stopped in 2012. After that he struggled to pay for doctors’ visits and MRIs on his constantly aching neck. He mostly lived with his mother in Tallahassee, Florida, until he finally got his own place earlier this year. In 2019, he spent 10 days in jail for failing to pay attorneys in a long-running custody battle over three of his kids.

When Williams finally did get approved for NFL disability payments this year it was based on what a program-appointed neuropsychologist determined were psychiatric impairments that rendered him totally and permanently disabled.

The approval was for the “Inactive B” level, which pays $5,000 a month to players who apply for benefits after they've been retired 15 years. It’s less than half of what he would have received if approved at “Inactive A,” for players before the 15-year mark, which pays $11,250 a month.

Williams appealed, arguing for the increased benefit because the 2023 approval was based on identical medical information used for a December 2019 application filed before the 15-year deadline and rejected.

The program rejected the 2019 application in part because the plan-appointed orthopedic doctor who examined Williams ruled he could participate in sedentary and desk work. The denial letter made no mention of the 2009 exam included in the application, with the crossed-out 27% whole-person impairment rating replaced by the 24% rating.

The letter leaned heavily on Williams missing appointments with the plan-appointed neurologist and neuropsychologist — appointments Williams said in advance he would miss. The letter acknowledged receiving nearly 160 pages of doctors’ reports, brain scans and neurocognitive analysis done on Williams by his own doctors, all of which indicated extensive impairment. But it said the committee that makes final decisions “did not find that these records support a finding of total and permanent disability at this time.”

“They tell you to send in medical records with the application,” Williams said, “but then they don’t really look at any of that. It doesn’t make sense.”

Because program rules required him to wait a year and then the COVID-19 pandemic caused more delays, Williams couldn't reapply until this year — after the 15-year window had expired.

But in any case, Williams said, the league should have been well aware of his issues — and not only because of the medical records he submitted over the years.

“I’ve called their suicide hotline when I’ve had episodes. They don’t help you,” he said. “I’ve been telling them about my neck for decades. They’ve seen the fracture and the tear in my shoulder for decades. Bottom line, they don’t care.”

___

EDITOR’S NOTE — This story includes discussion of suicide. If you or someone you know needs help, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-8255.