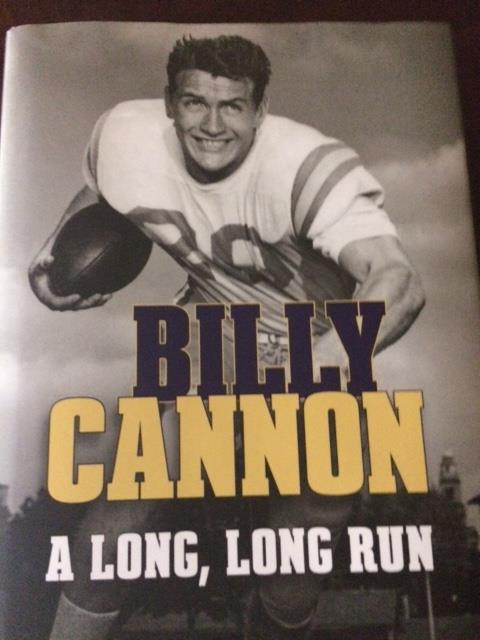

BATON ROUGE – There is nothing counterfeit about "A Long, Long Run," the recently released biography of legendary but true LSU tailback Billy Cannon – a duplicitous mixture of matinee idol Heisman Trophy winner in 1959 and hoodlum youth turned convicted counterfeiter in 1983.

Roguishly handsome with a James Dean wave of hair and a surname straight out of central casting, Cannon had a cinematic flair on the gridiron. His "Heisman Moment" came on a muggy, haunting Halloween Night in Tiger Stadium in '59 when No. 1 LSU hosted No. 3 Ole Miss in one of the first "Game of the Century" episodes. Though the game was not televised, replays of the "Halloween Run" have still not stopped and continued for decades on Halloween night television sportscasts throughout Louisiana.

With about 10 minutes to play, Cannon rebelliously grabbed a bouncing punt on a muddy field at his 11-yard line, ignoring Coach Paul Dietzel's rule prohibiting such devilish deeds inside the 15. He proceeded to break the tackles of five seemingly ghostly Rebels on his way to an 89-yard touchdown and 7-3 victory for the defending national champion Tigers, who stood 7-0 on the season with their 19th straight victory. And Cannon and Tiger Stadium have basically been the "Legend of Sleepy Hollow" ever since.

There were other long runs throughout Cannon's life – from would-be tacklers and from the law that he could not elude. He was the epitome of a 1950s teen rebel from the blue collar side of town.

"Yeah, James Dean with a slow car," Cannon says early in the book.

Cannon's self-deprecating humor slices through the 215 pages published by LSU Press. When old friend and former LSU track coach Boots Garland drops by to check on him shortly after his counterfeiting arrest in the summer of ‘83, he asks, "Billy, is there anything I can do?" And Cannon says, "Yeah, Boots, you got change for a hundred?"

First time author Charles N. deGravelles, a former journalist who has been ministering at the Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola for more than 25 years, does not chronicle a cleaned up "Happy Days" version of LSU's golden boy. He focuses as much on Cannon's crimes as on his spectacular football career. The author befriended Cannon after Cannon came full circle in a way in 1995 by becoming director of dentistry at the prison less than a decade after his prison term of nearly three years in Texarkana, Texas, from 1983-86 for counterfeiting.

"I wanted it told with no cover-up, with no sugarcoating" Cannon said in a recent interview. "Just tell it as it was."

The opening pages dive into a pre-counterfeiting arrest of Cannon. In the summer of 1955 before his senior year at Istrouma High in Baton Rouge, he and some friends were arrested for theft. Cannon and his "gang" would hang out near the neighborhood bars and clubs near their homes in north Baton Rouge and shake down men they saw entering hotel rooms with prostitutes. Once, Cannon and his cohorts followed a church deacon to his mistress' house.

"We were waiting for him next to his car when he finally came out," Cannon says in the book. "All he wanted to do was give up whatever he had on him – a watch, some money – and get out of there."

Most of their victims were in this embarrassed, cooperative state, but Cannon and his cronies would use force when needed. Then they would then sell the stolen items or divide up the booty. And they got caught. Cannon and the others pleaded guilty and received 90-day suspended sentences. Already a well-known high school star, Cannon saw his name in a headline in the Baton Rouge Morning Advocate and was embarrassed for himself and his family.

"We were not only stupid. We were criminal," Cannon said. "We were taking advantage of people. What we were doing was wrong. We knew it was wrong. But it was adventurous. It was fun, and it was profitable. I was a thug. If I wasn't, I was closely in the making."

Cannon straightened up quick and married his high school sweetheart, Dot Dupuy, in their freshman year at LSU. Though easily the largest star, he bonded with teammates not as a prima donna, but like Roy Hobbs in "The Natural."

"Anything he tried, he was the best at. It was part of who he was," says LSU teammate Hart Bourque in the book.

"From the beginning, Billy was highly supportive of his teammates – to the point where he was projecting attention on them and away from himself," LSU teammate Scooter Purvis says.

"The team concept was so important to me – just to say I'm one of them," Cannon says in the book.

Cannon went on to lead the Houston Oilers to AFL titles in 1960 and '61 before moving on in 1964 to the Oakland Raiders, where he switched to tight end and played in Super Bowl II in the 1967 season. He retired after the 1970 season with Kansas City. Always a good student who found school easy, he had studied dentistry in the pro football off-seasons and opened a successful orthodontist practice in Baton Rouge while raising four daughters and a son with Dot.

Then he tried real estate on the side, and naturally was very good at it and kept buying property and buying property and some horses. Soon, though, the economy turned sour, and Cannon was extremely overextended as the 1970s became the 1980s. "It was typical Billy Cannon," Cannon says in the book. "Everything had to be more and bigger."

And there was not enough real money to go around. "Looking back, I was too heavily invested," Cannon said.

Soon, Cannon graduated from street-wise shakedowns to a $50 million counterfeiting scheme with teammates of a different sort.

On Saturday, July 9, 1983, the Secret Service, which Cannon knew was trailing him for months, raided his home in Baton Rouge while he was at the Fairgrounds horse track in New Orleans. Dot was home and unaware of the tacklers that had been pursuing her husband or why.

"How do you love somebody and want to kill him at the same time? It wasn't about me," Mrs. Cannon says in the book. "I was angry because it hurt the kids."

So many asked why. "If you are asking me why I did this? I still don't know why. What I did was wrong, terribly wrong," Cannon said in court.

"It was hell, pure hell," youngest child Bunnie Cannon, who is executive director of institutional advancement and fund raising at the LSU president's office, says in the book. "All those deals, and there was lots of drinking that went with each one. I don't think he was making the best decisions."

Cannon began his jail term at the low security Federal Correctional Institution in Texarkana, Texas, in September of 1983 just as his son Billy Cannon Jr., a highly recruited football star out of Broadmoor High in Baton Rouge, was beginning his senior season at Texas A&M. In the summer of 1986, Cannon was free after having his five-year sentence reduced to less than three years on good behavior.

Cannon returned to his orthodontist practice, but struggled financially and eventually closed the practice before becoming the director of dentistry at of all places – the maximum security Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola – in 1995. During the job interview, Angola warden Burl Cain told Cannon, "I hear you've got a lot of experience." Cannon said, "Which side of the razor wire do you want it on?"

Cannon, now 78, survived a stroke in 2013 and continues on both sides of that wire nearly every day as he remains head of dentistry at Angola.

"What I've done is what I've done, and it's there," Cannon said. "I wanted young people to read the book – young men - because there are going to be temptations and trials, and you're going to have problems making decisions. My hope is that when they read the book, they will take the high road."

Cannon could give current LSU tailback and 2015 Heisman favorite Leonard Fournette a copy at the Heisman ceremony in New York on Dec. 12. "I'm going back to New York one more time, and that's when Leonard wins the Heisman Trophy," Cannon said.

Fournette met Cannon at LSU's spring game in April. "He told me to keep doing great things, keep pushing," Fournette said this week.

He does not want Fournette to look back the same way he does.

"Many, many regrets," Cannon said. "Would I do it over the same way I did it? Definitely not. Life is for living, and I've lived a good one. Made some mistakes. Some people make small mistakes. I made bigger ones."

And that long Halloween Run never seems to end. It is played on the huge video screens at Tiger Stadium before every LSU home game.

"All you have is that grainy film from a distance," former LSU receiver Doug Moreau, a color analyst for LSU games since 1972, says as "A Long, Long Run" comes to a close. "But it shows what it shows. That one guy, one giant, knocking down all the pawns, finishing in the end zone," he says.

"I've had a great run, and I hope people enjoy reading the book," Cannon said. "Sometimes, it's funny."