BATON ROUGE - LSU's version of “Glory Road” featured everything but the racial overtones and the Hollywood ending.

The Tigers’ trip, which included a detour down the Chicken Pox Highway, happened in 1986 - 20 years after Texas Western's unprecedented five black starters dunked No. 1, all-white Kentucky, 72-65, in College Park, Md., for the 1966 college basketball national championship about which the film, “Glory Road” was made in 2006.

LSU captured its glory when its two white starters surrounded a black All-American from No. 1 seed Kentucky and delivered a textbook layup and 59-57 win at the NCAA Southeast Regional final in Atlanta for a trip to Dallas as the highest-ever No. 11 seed at the Final Four.

Kentucky hit Atlanta in 1986 at 32-3 on the season with Southeastern Conference regular season and tournament titles, but lost just as No. 1 Duke at 32-3 with Atlantic Coast Conference regular season and tournament crowns lost to upstart No. 4 seed LSU, 62-54, also in Atlanta in the Sweet 16 round of the NCAA Tournament in 2006.

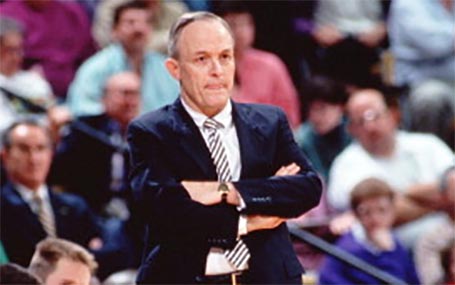

"There are some bizarre things the 1986 and 2006 teams have in common," said former LSU coach Dale Brown, who guided the Tigers to Final Fours in 1981 and ’86. "LSU beat Texas in overtime in 2006. We beat Purdue in overtime in 1986. LSU beat Texas A&M on a last-second shot by a Louisiana kid (Darrel Mitchell) in 1986. We beat Memphis State on a last-second shot by a Louisiana kid (Anthony Wilson). Our NCAA Regional MVP was from Louisiana — Don Redden. The Regional MVP in 2006 was from Louisiana — Tyrus Thomas. We beat a 1, 2 and 3 seed. The ’06 team beat a 1 and 2."

LSU was the highest seed to reach the Final Four until George Mason upset Connecticut to get to the Final Four in Indianapolis in 2006.

"I sat down to watch that George Mason game pulling for Connecticut, because I didn't want another 11 seed to get in," said Brown, who has remained in Baton Rouge since his retirement from LSU in 1997. "Then as the game progressed, I started hoping George Mason would win because of their attitude. Then my team got more publicity because another 11 seed made it."

The morning after LSU and then-Coach John Brady upset Duke in 2006, Brown called Brady to share the spooky similarities between '86 and '06.

“Only Dale thinks that way,” said Brady, who just retired from coaching at Arkansas State.

CBS analyst Billy Packer said only Dale Brown could have taken that 1986 LSU team as far as the Final Four despite a Chicken Pox quarantine, a star signee’s dismissal, a star player’s academic suspension and a trilogy of close losses to Kentucky before final redemption. But this is no Disney movie. And as the opening narration of Brian's Song says, "Every true story ends in death.”

Well, this is a true story.

Don Redden, a 6-foot-5 senior from Monroe, had the ball and saw 6-6 Ricky Blanton, a sophomore from Miami, open in a two-on-one break with Kentucky 6-8 senior All-American Kenny Walker between them.

"Don was on one wing, and I was on the other," Blanton said. "Don threw a cross-court pass to me, and I laid it up to score."

Walker could not make the play this time as he did in the three previous games Kentucky beat LSU that season – 54-52 in Baton Rouge, 68-57 in Lexington, Kentucky, and 61-58 in the SEC Tournament in Lexington. Instead, Blanton's layup put the Tigers ahead 59-55 with 17 seconds to go, and they held on for the 59-57 win.

"Not bad for a white guy," black LSU assistant coach Ron Abernathy told Brown with a biting laugh, repeating a joke he and Brown shared frequently when Blanton made a play.

Then Brown helped cut the nets down with his teeth.

"After losing to them three times, the pride that LSU left the floor with that night sent chills through you," said LSU associate athletic director Bo Bahnsen, who was an administrative assistant coach in 1985-86.

"We were the biggest thing in the state, which really had a struggling economy at the time because of the oil bust," Bahnsen said. "We were playing for more than LSU, we thought."

Twenty years later in 2006, LSU would play for a hurricane-ravaged state just months after Katrina.

In the fall of 1985, the only storms were on the LSU team. Forward Jerry Reynolds had left early for the NBA. Before the season could get started, Brown kicked star 7-1 signee Tito Horford of the Dominican Republic off the team. Horford transferred to Miami and was at LSU’s Final Four in 2006 because his son Al was a forward for the Florida Gators who won that national championship.

Another LSU center, team captain Nikita Wilson, was found academically ineligible for the spring semester in ’86 for academic reasons along with backup guard Dennis Brown. And backup center Zoran Jovanovich tore his knee up in a pickup game and was lost for the season. So Blanton moved from guard to center.

“We’ve gone from an NBA-size team to a big junior high team,” Redden said at the time.

Then the chicken pox hit. First Blanton got it briefly. Star sophomore forward John Williams of Los Angeles and backup freshman forward Bernard Woodside got the worst of it and were hospitalized for a week. The team was quarantined for a week, and Brown resorted to recruiting 6-7 Chris Carrier, a safety on the LSU football team from Eunice.

“The whole season was a test,” said Brown, who was 50 that season.

Brown somehow got the SEC to postpone a Jan. 25, national TV game at Auburn on NBC as Brown said he was down to only a handful of healthy players.

“I think coach may have used a red marker on some of the kids,” Bahnsen said.

The schedule change forced LSU to play four road games in five days, but Brown had his cause. After four straight valiant efforts in defeat at Florida, at home against No. 8 Kentucky by two, at Georgia and at No. 12 Georgetown by two, the Tigers won that game at Auburn by two. And LSU was off to five wins in seven games and the NCAA Tournament.

After losing six of eight games as the roster depleted in mid-January through early February, the Tigers finished 26-12 overall and 9-9 in the SEC.

"Coach Brown just channeled all of that into motivation," Blanton said. "Each day, we were ready to go through a brick wall, he had us so jacked up."

A week after that Final Four-swiping win over Kentucky, LSU finally hit the wall in Dallas on March 29, 1986, losing 88-77 to eventual national champion Louisville in a Final Four semifinal.

Redden led LSU with 22 points in that last game as Blanton had 12 rebounds and scored nine points against Louisville. Blanton remained Redden's wing man after Redden went on to play professionally overseas. Whenever Redden returned to Baton Rouge, the two were inseparable on the court and off … until March 8, 1988.

Redden died that morning in Baton Rouge. It was later learned he had an abnormal heart. He was 24 and died three months after his idol, Pete Maravich, died of a similar ailment at 40. Redden is buried near Maravich in Baton Rouge.

"Even though he's gone home to glory, he's ever-present in our lives," Glenda Redden, his mother, said in an interview 10 years ago.

The Don Redden Classic at his alma mater, Ouachita Parish High, remains to this day in Monroe. So does a scholarship in his name at LSU.

Blanton struggled with Redden’s death for years and still does at times.

"He just wasn't a teammate," said Blanton, who would reach two more NCAA Tournaments with the Tigers in 1988 and ’89 and has been a color analyst for the radio broadcasts of LSU basketball games since 2009.

Don Redden happened to visit Blanton the day before he died.

"He came by the dorm to say hello," Blanton said. "We talked maybe 15 minutes. He was thinking of going to law school that fall. He was excited."

He was excited that magical night in Atlanta when he saw Blanton break open.

“Don was on one wing,” Blanton said, “and I was on the other.”