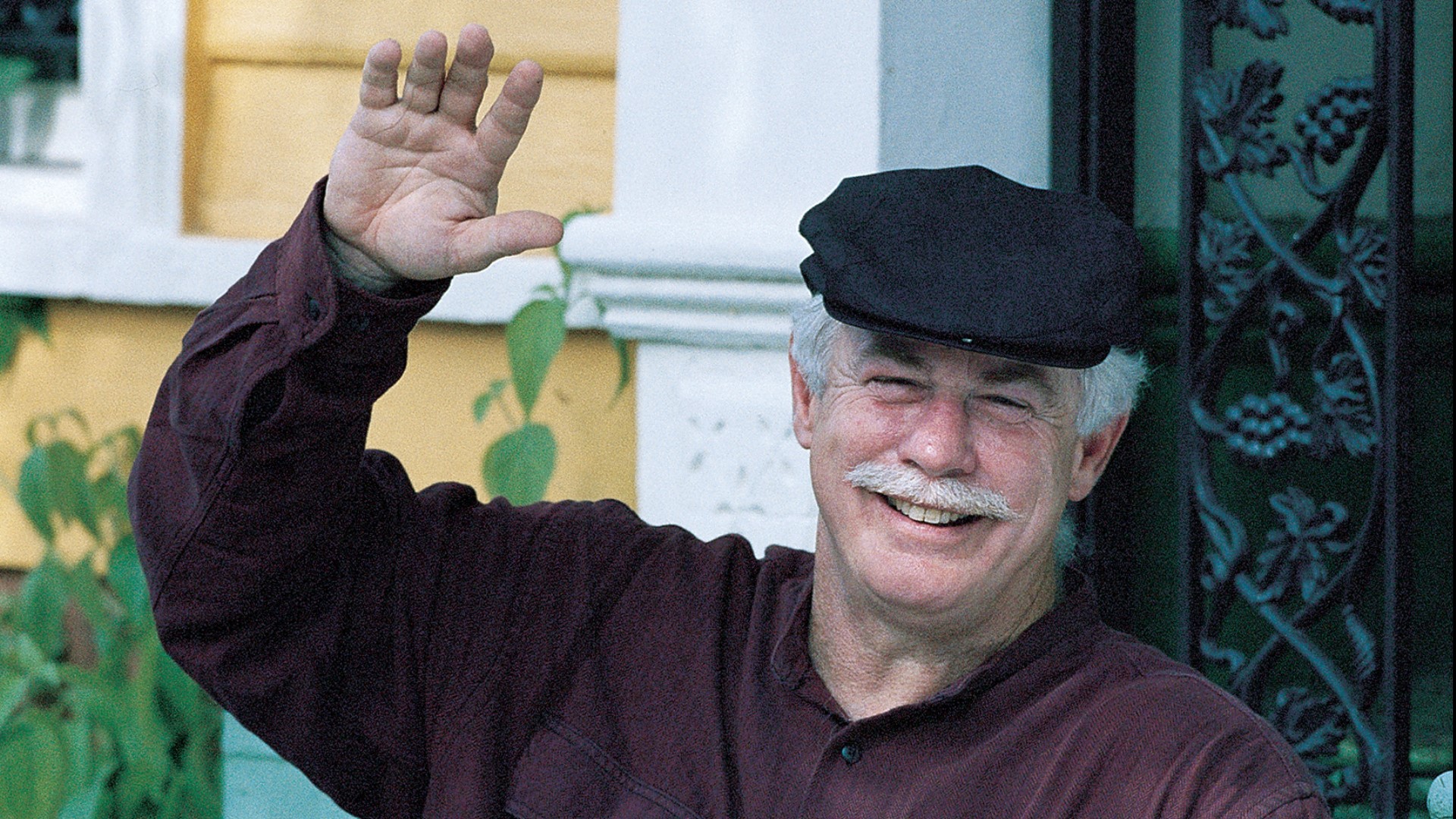

For decades, his voice was the voice of New Orleans.

On paper, Ronnie Virgets wrote the way he spoke, and on TV and radio he spoke like the dyed-in-the-wool New Orleanian he was, his gravelly yet soothing voice telling stories about the people and places that make this city such a one-of-a-kind place.

Virgets died Monday. He was 77.

His journalism career began in the mid-1970s, and his name and face were connected to stories that were printed in The Times-Picayune and Gambit and aired on WWL-TV, WDSU-TV, WYES-TV, WGNO-TV and WWNO-FM.

His stories were often about the everyman New Orleanian. His subject matter was no doubt inspired by his own blue-collar background.

Virgets was born April 16, 1942, at Mercy Hospital in Mid-City and grew up in that neighborhood where he threw newspapers (at least until one morning it was so cold, he tossed his copies into Bayou St. John and went home). He was as comfortable talking to a garbage man was he was the King of Carnival.

Virgets attended Sacred Heart Elementary School on Canal Street and St. Aloysius High School (now Brother Martin High School), where a teacher encouraged him to develop his writing talents. At Loyola University, he joined The Maroon, the campus newspaper, and wrote a sports column titled “On the Virg.” While at Loyola, he also wrote freelance stories for The Picayune.

But his journalism career would not happen immediately after graduation.

Between 1965 and 1968 he served in the U.S. Army and saw a tour of duty in Vietnam. When he returned home, he tended bar, owned a pool hall and worked for a small public-relations firm.

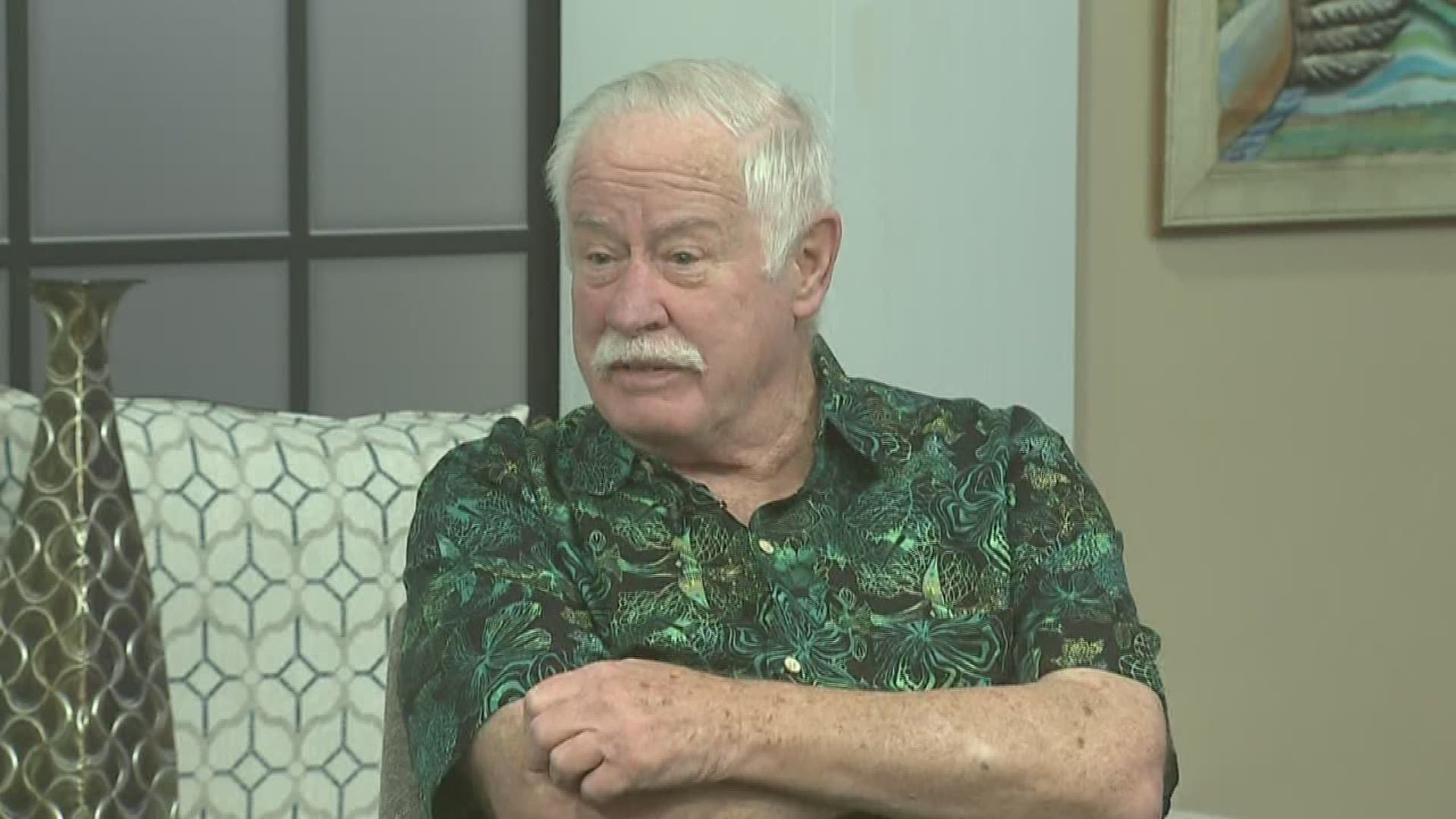

“I didn’t really start writing (until) I was in my mid to late 30’s, so ... I wasn’t a prodigy,” he said during a 2017 interview on WWL-TV, downplaying his talent as he was known to do.

He went back to writing freelance sports features for The Picayune for a little while in the mid-70s. But he was introduced to horse racing as a boy and parlayed that love into a job when he covered the horse-racing circuit for the Racing Form, part of the time near Philadelphia.

Once he returned home to New Orleans, he continued to cover the racing beat in his “Railbird Ronnie” columns in The Picayune, before he became a feature writer for the newspaper’s old Dixie Roto magazine and, eventually, a metro column.

A disagreement with the paper’s management about one of his columns would cost him his job at the newspaper.

“I’ve been laid off by a lot of people. I’ve had many a job and in more than one of them I was kind of asked to leave early,” he acknowledged during the 2017 interview with WWL.

But the loss of his job at The Picayune was far from the end of his career. In fact, it launched his second phase -- broadcasting.

Former WWL anchor Bill Elder recruited Virgets to write features for his weekly show “Bill Elder’s Journal.”

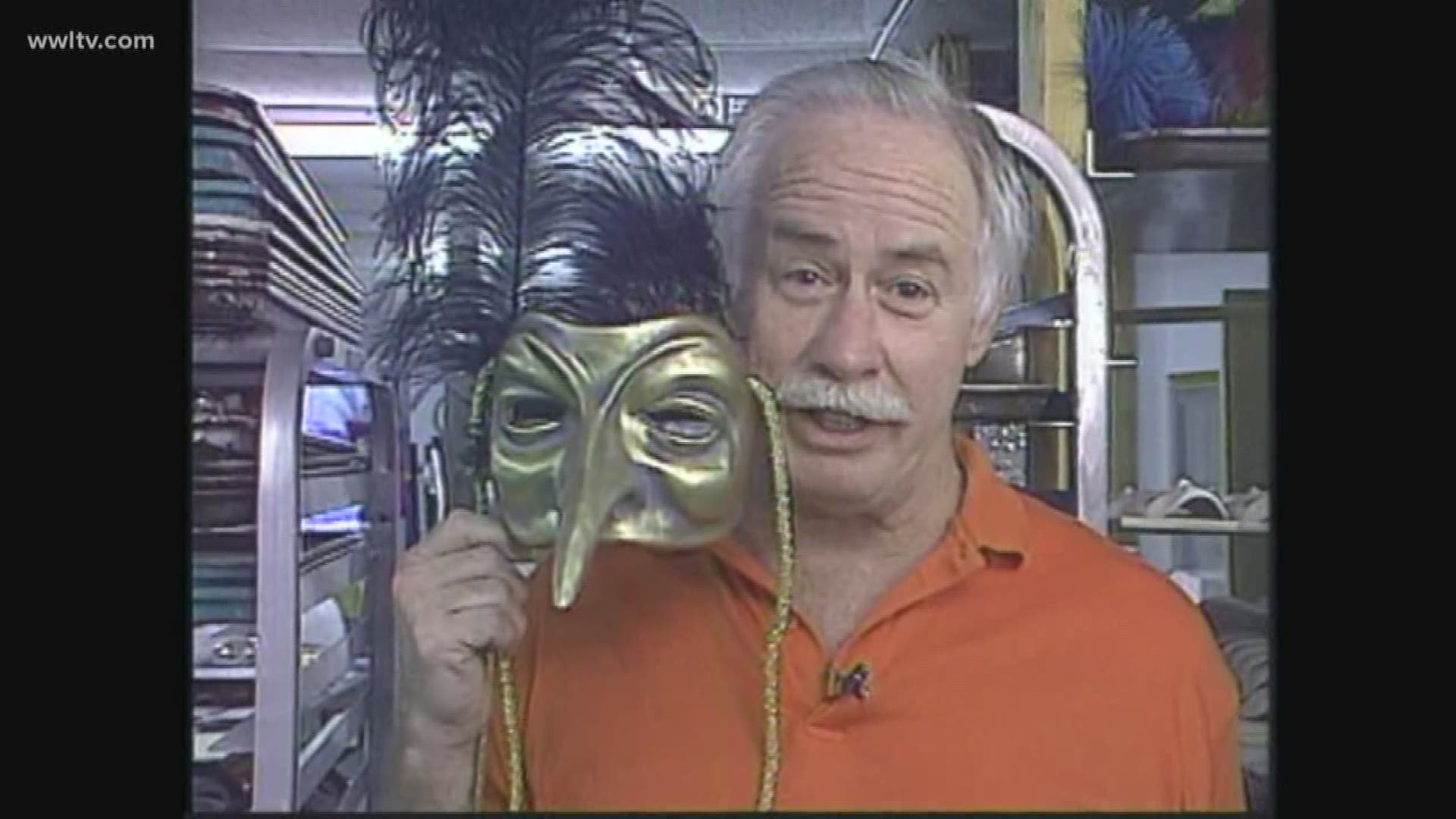

On WGNO, his pieces aired on “Real New Orleans,” a feature show that focused on the New Orleans area. His stories were far from the standard 90-second pieces broadcast on the evening news and featured his unmistakable y’at voice.

“I was considered lucky. I go back now … and look at some of them I realize gee you had a lot of time. People must have been hollering, ‘Get him off! Get him off!’ But yes, some of them were atypical in terms of length.”

But they were so well written and edited -- the words and video playing so well off each other -- that it’s hard to believe anyone would have asked for them to be shorter.

Topics for his TV pieces on WGNO, WWL and WDSU included everything from a history of the Ursuline nuns in New Orleans to musing about the evolution of Veterans Boulevard.

After a massive fire destroyed the old grandstands at the Fair Grounds, Virgets broadcast a nearly seven-minute eulogy on WGNO for the place that was an important part of the city landscape for so many people so many years. He wrote it in a way that only he could.

“Old race tracks burn well. In fact, they burn spectacularly,” the piece began. “If you were there the night the Fair Grounds burned, you got to smell history and feel its heat.”

WWL-TV chief photographer Brian Lukas recalled working with Virgets on his first story for Channel 4. In a world where reporters are dressed to impress, manicured and coiffed, Virgets was an outlier.

Lukas recalled a man who showed up with his shirt untucked, hair unkempt and with stubble on his face. But the story was so good, Lukas said, that none of that mattered. "It was one of the best stories I've ever done."

"Some people say he was like Hemingway. But he wasn't in the same league," Lukas said. "He didn't have a league."

Virgets, who was king of Krewe du Vieux in 1996, continued to write for print while on TV, penning columns for Gambit. Regardless of the medium, he wrote every story the same way: by hand.

“He is fully capable of using a computer, but he prefers handwriting on lined legal pads,” New Orleans Magazine writer and editor Liz Scott Monaghan wrote in a 2002 feature on Virgets when the Press Club of New Orleans presented him with its Lifetime Achievement Award. “According to an editor, he once turned in a story written on five cocktail napkins stapled together at the corner. But it was a good story, and it was published.”

Many of those columns -- some of which were award-winning -- made their ways into three books he published. Often sprinkled in were quotes from philosophers.

“I go back and I look at some of them and I go, ‘Where did you get this from?’ I don’t know whether I was just showing off or what. But for a while I did kind of get to a point where I’d throw in a quote here to sort of, like, ‘Let them know how well read you are,’” he said matter-of-factly on WWL.

An essay on his ordeal riding out Hurricane Katrina in Lakeview was broadcast on NPR and was later published in one of his books. After being rescued from the flood, he asked where he was being taken. The Superdome, he was told. "What else ya got?" he asked.

“Ronnie was a Crescent City character and a true treasure. He was “Naturally N’Awlins” before the term was invented,” said Mardi Gras historian Arthur Hardy, who published two of the books. “We may never see a better storyteller.”

His last book, “Saints and Lesser Souls,” was published in 2017, several years after he moved on to a quieter life in New Roads, outside of Baton Rouge. Asked during a WWL-TV interview if he had run out of stories to tell, he laughed.

“No, I haven’t quite run out of stories. I’ve just run out of energy.”

Virgets is survived by his longtime partner, Lynne Jensen; a brother, Tommy Virgets; a son, Michael Virgets; daughters, Stephanie Whittington and Tara Mackey and seven grandchildren.

Funeral services are pending.