MOBILE, Ala. — It's a Saturday morning in Mobile, Alabama, and Mobile resident Darron Patterson is filled with purpose.

"God put me at this moment in life for this," Patterson explains.

He helped organize a festival to celebrate the people who founded the town where he was born and raised. It's called Africatown.

It's a small community of about two-thousand people in Mobile- a two-hour drive from New Orleans.

"It's no different than any African-American community in a lot of neighborhoods....in a lot of metropolitan cities," explains Patterson.

There is something that makes Africatown different. It was founded by a group of Africans who were enslaved and brought to America 50 years after the slave trade was made illegal in the U.S.

The Last of the Enslaved

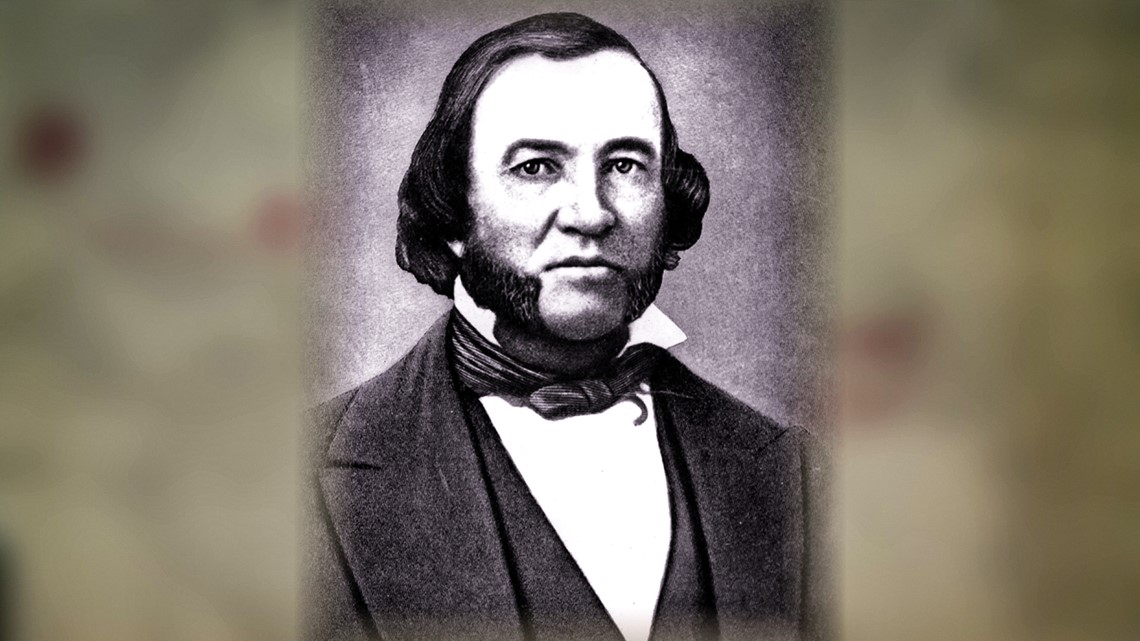

"Timothy Meaher was slaver. He was more than a slaver. He was instrumental in the process of getting slaves here," says Patterson.

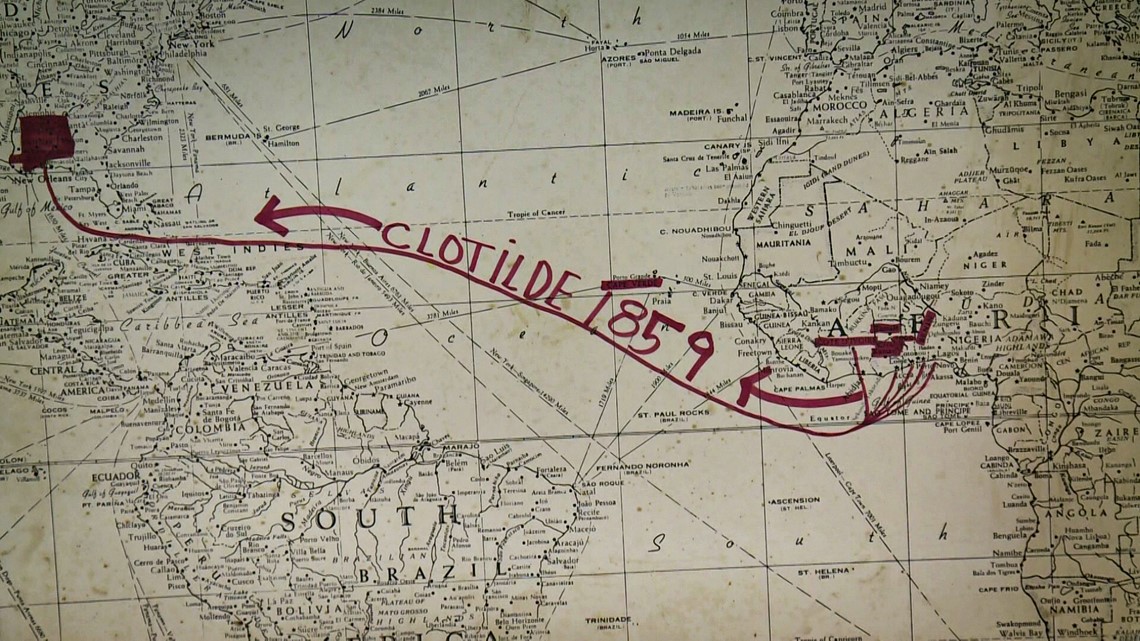

He wagered he could defy the law and bring slaves to the U.S. So he commissioned a ship for the journey- the Clotilda.

Patterson continues, "So he commissioned the Clotilda with Captain William Foster, a friend of his from Maine."

They took the ship to an area of West Africa that is now known as Benin.

"The bad part about the whole story is we were sold to Timothy Meaher by a rival tribe," says Patterson.

The Dahomey tribe captured men, women, and children of the Yoruba tribe and sold them to Meaher.

110 Africans were forced on aboard the Clotilda.

"You are sleeping where you piss. You are sleeping where you (expletive). You are sleeping where you eat .You are eating where you do all this other stuff. For two months, and you can only come out of the cargo hold one day a week for an hour a day. And that's only so your muscles won't atrophy and you won't be any good to anybody," says Patterson.

Once they reached Mobile in 1860, the slaves were put on a riverboat, and to hide the crime, Foster burned the Clotilda and sunk the wreckage in the Mobile River.

Many of the residents of Africatown grew up hearing about the Africans who survived slavery and went on to found their hometown.

Patterson was an adult by the time he came across the story. Some people told him that it was just a myth, and some were adamant that it never happened.

"My great-great-grandfather was Pollee Allen. Kupollee Allen was his African name," says Patterson.

Patterson's great-great-grandfather was one of the Africans who came to America on the Clotilda back in the 1800s and founded Africatown.

"My folks told me nothing. I had no clue who I was until I became an adult," Patterson explains. "And I tell people all the time. I truly believe that my folks were ashamed of how we got here."

"When they found the Clotilda, everything changed."

The Clotilda was real

Last summer, it was confirmed that the remnants of the slave ship were found in Alabama's Mobile River.

It followed a year long search that all started with curious journalist named Ben Raines.

"A friend of mine called me and said, 'Why don’t you go look for the Clotilda?'

"Well, is it missing?" asked Raines. "I didn't even know."

But once he learned the story, Raines was determined to give the people of Africatown evidence that their history was real.

"It's the only slave ship that brought people to America ever found."

The story gained attention all around the world.

"It brought a level of recognition that Africatown had not had before," explains Mobile County Commissioner Merceria Ludgood. Her office helped fund the search efforts for the Clotilda, and she's seen how its discovery has suddenly thrust Africatown into redevelopment.

"We've seen interest from public sector and private sector from investment there, and that’s what we needed," says Ludgood.

Rebirth in Africatown?

Africatown could use some investment.

When Patterson was growing up in the 50s and 60s, the area was close knit community with lots of businesses.

"We had post offices, shops, stores, doctor's offices. We had everything. This was a self-contained community," explains Patterson.

Today, Africatown is filled with rundown and dilapidated houses, there are parts that are historic.

"There were houses there that were historically accurate," Ludgood points out.

Some of the homes that the Africans built are still standing, and the original cemetery where some of the founders of Africatown are buried is still being used.

The founders also created a school.

"Mobile Country Training School is legendary. It established in 1880 by the Africans to make sure that the young African men and women know how to go forward and be viable citizens," says Patterson.

Lots of people want a say in what happens next, especially the descendants of the Africans who built the town.

Patterson is spearheading the effort to organize the descendants. He is the president of the Clotilda Descendants Association.

"The descendants...our goal is to build an African-American museum and cultural arts center.

A Lasting Pain

Patterson says that redeveloping Africatown is great, but he says more needs to be done to make things right.

Patterson points out that, "the owners of that slave ship, the Clotilda, they are still very prominent in Mobile."

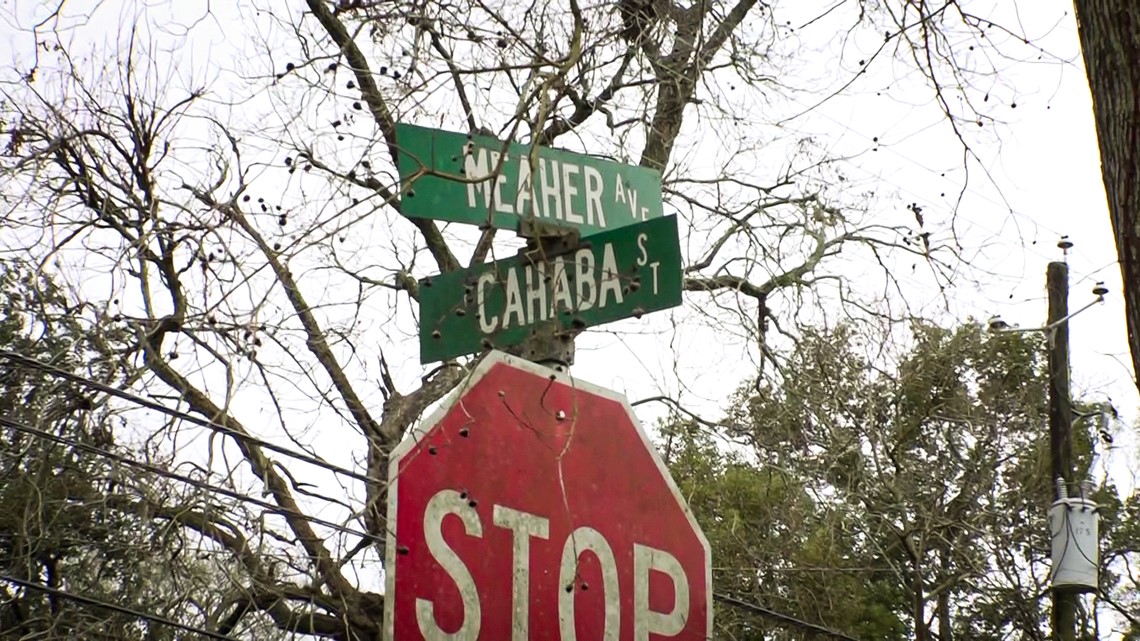

There is Meaher State Park and Meaher Avenue, which runs through Africatown.

"Their shadow is still looming over you, even though you know those days are passed. You know that they are responsible for us being here," says Patterson.

Patterson says the prominence of the Meaher family in the area feels like disrespect.

"Once the Emancipation Proclamation became law and we were free. We said, 'We are free now. Can you give us a boat so we can go back home?' No."

"Well, can you give us some land so we can establish ourselves here?' No."

Patterson's great-great-grandfather and the other Clotilda survivors worked to buy some of the land, but not enough of the land.

Descendants of the Clotilda survivors want a fair price to buy the land in Africatown the Meaher family still owns, and they want to hear something else from the Meaher family.

"I am sorry for what happened. I didn't have anything to do with it, but what can we do to help you make it right,' is what Patterson hopes to hear from them. "Don't just sit back and not say anything."

To those who would say leave the past in the past, Patterson feels that the present is being stained by what happened more than a century ago.

"Here we are again in 2020, and the disrespect continues. That's what most disheartening and brings anger."

What will become of Africatown and who will make that decision is yet to be known, but what Patterson knows is that he has a responsibility to his great-great-grandfather, Kupollee Allen.

"Our job now as the descendants is to keep their legacy alive."

► Get breaking news from your neighborhood delivered directly to you by downloading the new FREE WWL-TV News app now in the IOS App Store or Google Play.

WWL-TV reporter Sheba Turk can be reached at sturk@wwltv.com;