NEW ORLEANS — As we continue our look into solving crime in the city with our continuing series, Wounded City, many young people deal with untreated mental illness and there's a lack of services to help them.

Before the pandemic, the Louisiana Health Department said more than 1/5 of people in Louisiana had a mental illness, yet only 15% got treatment.

And the need has soared.

Just at LSU Health, there are 18,000 behavioral health appointments yearly, with only 63 medical professionals to see them.

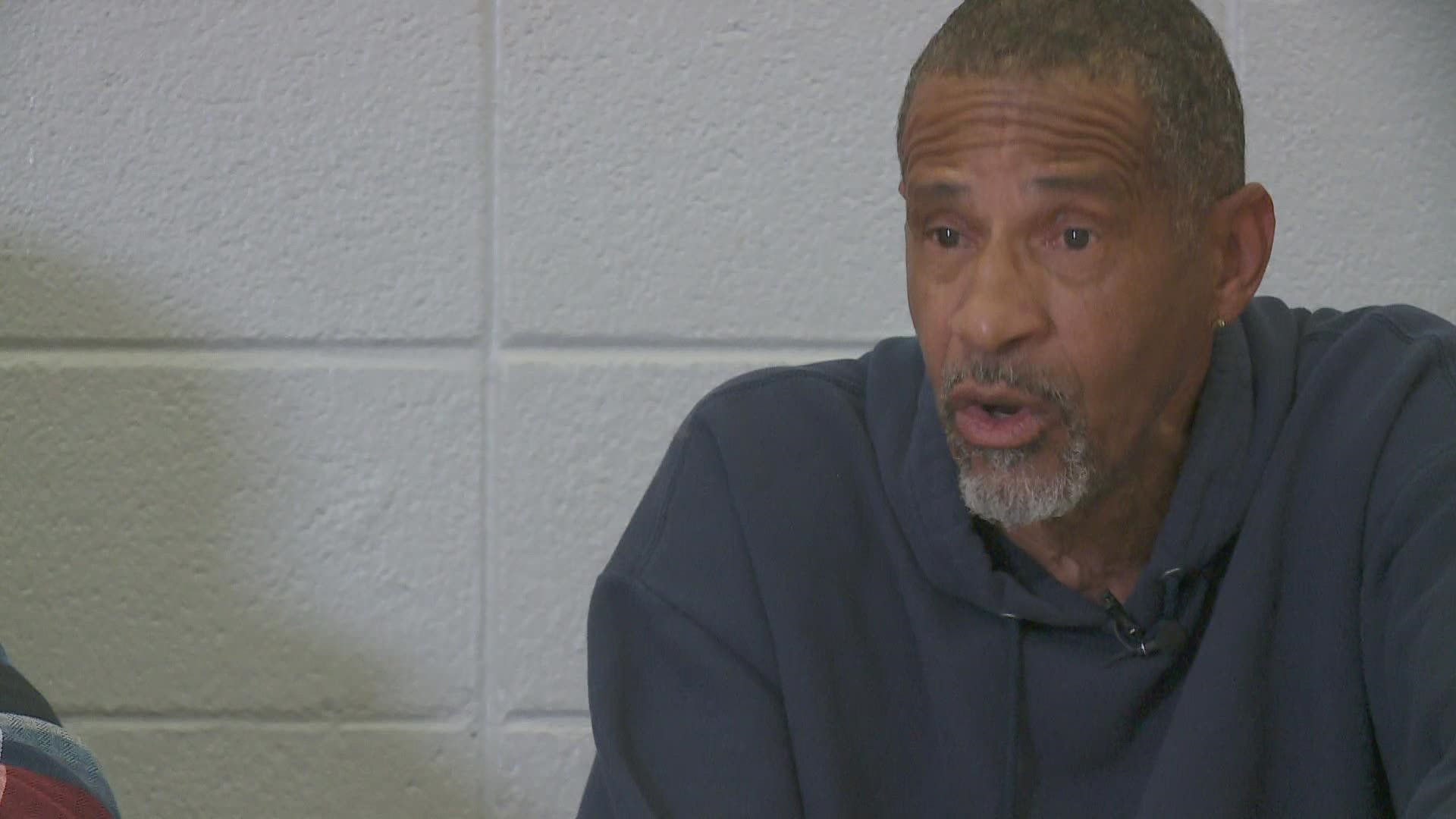

When Ronald “Cadillac” Roberts talks about his son, he feels decades of pain.

“This is where it gets emotional,” he said with a sigh. “He done spent maybe, I want to say, 27 years in prison, out of his 47 years of life.”

He remembers early signs of problems and medication that dulled his son as a child.

“We didn't know that it was a mental thing that needed to be addressed. So, lo and behold, that's when the trouble started," Roberts remembered.

Actor, author, and activist, Ameer Baraka grew up with a different type of brain disorder, dyslexia.

“Had somebody caught me in the third or the fourth grade, I'd have never gone to prison. I didn't like school, so I started selling dope. Most kids are going to sell dope and they're going to drop out of school if they can't read,” Emmy-nominated actor Ameer Baraka said.

“When kids are rejected at an early age, that's a very hard thing. They lose empathy skills and everything else if they are rejected earlier,” Dr. Stephen Phillippi said.

Chair of Behavioral and Community Health at the LSUHSC School of Public Health And Institute of Public Health and Justice.

Dr. Phillippi said that's because schools, and families and other groups are crucial to mental health, and emotional development.

“We certainly have a good idea that if we don't, early on, address emotional challenges in children, some not all, but some, may then move to a violent response as they get older,” Dr. Rahn Bailey, Chairman of the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Science at LSUHSC and Assistant Dean for Diversity and Community Engagement said.

Dr. Bailey, says when stressors are added, like being away from classroom structure during the pandemic, and fear from hurricanes and crime, on top of children already trying to survive serious family problems, that can lead to behavior problems.

“Every school has a security officer. They should have a mental health counselor so kids can go there before problem develops,” Dr. Bailey said.

“We know kids thrive in structure. They thrive in supportive environments that care about them. They thrive in environments where they find a purpose,” Dr. Phillippi explained.

It is important for them to belong to a supportive family, school, sports team, band, choir, or group.

“Belongingness matters to children, and young adults, and in the absence of belongingness, one certainly may, not always, but certainly may, unfortunately, look for that sense of belongingness in what we historically like to call gangs,” Dr. Bailey said.

“You'll notice in all these carjackings, they're not done by individual kids running around. This is groups of kids who have decided this is how we belong,” Dr. Phillippi said.

“Even if you don't change thinking when they are very young, you better get them by adolescence," Dr. Peter Scharf, Criminologist at LSU Health said.

And while the doctors say children and adolescents can be taught empathy and problem solving, Dr. Scharf said mental health treatment won't necessarily work if not geared to specific proven programs, based around moral reasoning and consequences of anti-social behavior.

“We've got to have better treatments and better interventions, interventions that deal with cognitive behavioral deficits, value deficits and resistance to temptations," Dr. Scharf said.

While there are individual programs like Son of a Saint, that connect at-risk youth with caring adults, programs, funding and treatment are very limited.

“What I don't see is systematically all of these organizations working together, working together better with the city,” Dr. Phillippi said.

And they say programs are also needed for those imprisoned.

“How do we build that transition? And the current system isn't doing that. All it's doing is locking them up, and they're going to come back very unskilled very unprepared for life,” Dr. Phillippi said.

“Whenever he's released,” Roberts said of his son, “It's always, it's understood that he needs help, and hopefully we can find some help for him.”

And just as students get a physical to play a sport, doctors say it would make sense early on for everyone to get a mental screening.

“Now if you look at extreme violence in a lot of individuals, do several of them a lot of them have mental health conditions as well? Absolutely. But just be very clear that mental health conditions aren't the cause of violence,” Dr. Phillippi said.

For more on Baraka’s new book on dyslexia, check out this link.