Rolland Golden, the acclaimed Louisiana artist whose realist paintings earned him an international following and exhibitions across the United States, Europe and the former Soviet Union, died Monday, according to his family. He was 87.

During a career which lasted more than six decades, Golden’s work was exhibited in more than 100 one-man shows and collected worldwide. He continued to attract interest in the art world just months before his death. Last spring, an exhibition at Mac-Gryder Gallery, “Beyond Vivid,” showcased some of his paintings. One of his recent works, “The Spirit Returns,” from his post-Hurricane Katrina series, is highlighted in the Historic New Orleans Collection’s new exhibit space which opened in April.

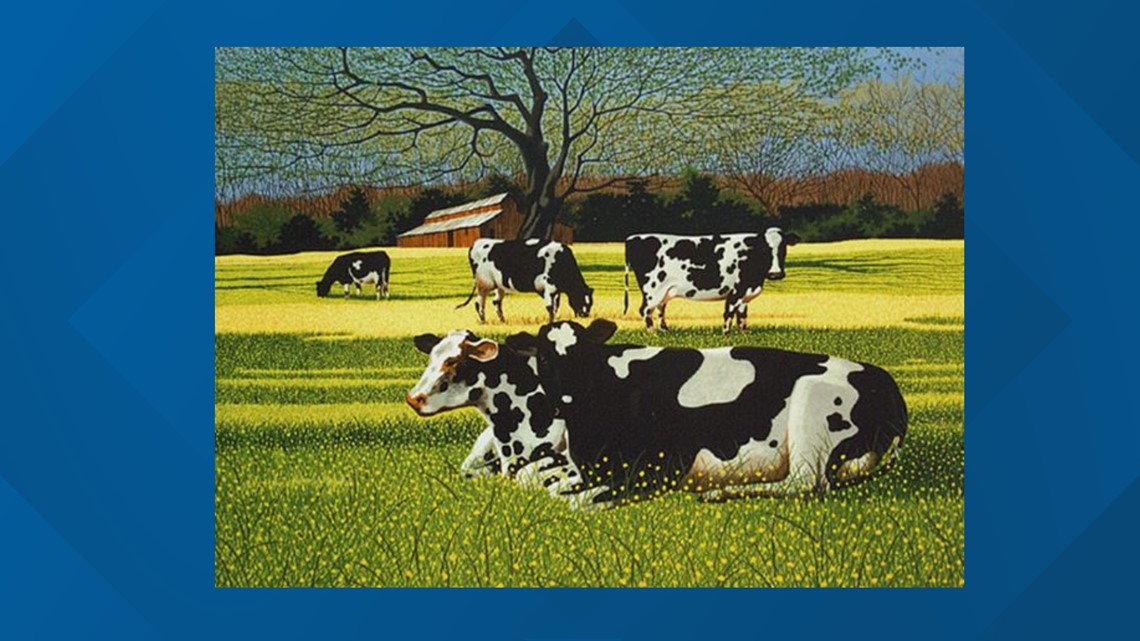

Golden, who was equally adept at using watercolor, oil and acrylic, sometimes called his work “abstract realism” or "borderline surrealism." His work showed a fondness for landscapes, particularly of the south and of Louisiana. Roads, trains, farms and even cows were familiar elements. “I can’t explain why I paint the things I do,” Golden said in 2015. “I just see something I like and I paint it and I try to do it my own way.”

“Perhaps a non-Southerner doesn’t feel the strange stirrings I feel and I find myself compelled to paint,” Golden said in Don Lee Keith’s 1970 book, “The World of Rolland Golden.” “However, I do think being a Southerner is a big factor in my personal outlook on art. I’ve tried, but I can’t quite put my finger on it. It has something to do with history and ancestors, and childhood and the very land itself.”

“Much of his work, whether you’re looking at the backroads of Louisiana with an old sharecropper’s shack, or his series on the Mississippi River, or his series on the Civil War, or his Katrina paintings and everything else that he’s done, is imbued with, in essence, the history of Louisiana,” said art critic John Kemp, in a 2015 Louisiana Public Broadcasting interview. It marked Golden’s selection by LPB as a Louisiana Legend award winner. “He paints the everyday world around you, the ordinary,” said Kemp. “It’s the minutiae of life that you see. I think what he does is he teaches you how to see the world around you.”

Kemp pointed out that while Golden often focused on southern landscapes, he also depicted scenes of New England, the Appalachians, New York and even the French countryside. “Golden has an eye that captures subtleties, be it a bright golden banana leaf hanging lazily over an old wooden fence in the French Quarter or cows grazing in a flowering French meadow,” Kemp wrote in a Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities profile.

“Blend the lonesome romantic realism of Andrew Wyeth with the metaphysical magic of Rene Magritte and you find yourself in the world of New Orleans native Rolland Golden,” wrote Times-Picayune art critic Doug MacCash in a 2014 review. He called Golden a “poetic prankster” whose work “always exhibits the highest standard of craftsmanship and a certain captivating charm.” That craftsmanship included making line drawings of his subject before beginning a painting, a technique Golden said he learned early in his career.

Born in New Orleans on Nov. 8, 1931, Golden said he had a lifelong interest in art. “It started with me as a baby,” he said in a 2015 WYES-TV interview. “My father was talented in art. I don’t ever remember not being with a pencil or something like that. I enjoyed it very much and I spent all my free time drawing.”

As a child, Golden’s father worked for AT&T and moved his family to Mississippi and then Alabama before returning to Louisiana, where Golden attended high school and college. He later said his love for the Mississippi Delta was formed during his childhood. "I didn't realize it at the time," he once told Southwest Art Magazine, "but the beauty of the rural South was making quite an impact on my young mind.”

After serving in the Navy for four years during the Korean War, Golden returned to New Orleans in 1955 and enrolled in the legendary John McCrady Art School, located on Bourbon Street. “He (McCrady) turned out to be the perfect instructor for my talent, such as it was,” Golden wrote in his 2014 memoir. “The aspects of art he emphasized were those for which I seemed to have the most talent: drawing, composition and perspective.”

While attending art school in the French Quarter, Golden also became part of the bohemian artist colony that thrived there in the 1950s. He and his wife, Stella, who married in 1957, moved into an apartment in the neighborhood and Golden opened a studio on Royal Street to create, display and sell his paintings. Like many French Quarter artists, many of his early watercolors depicted historic buildings, typical street scenes and jazz musicians at Preservation Hall. In the 1960s Golden also did illustrations for the French Quarter newspaper, The Vieux Carre Courier, many critical of the notorious plans for an elevated Riverfront Expressway in the French Quarter. For a time, he and his wife raised their three children in a house on Bourbon Street.

An early break in Golden’s career came courtesy of actor Vincent Price, who had been commissioned by Sears Roebuck to travel the country and find the work of local artists, whose paintings would be reproduced and sold in the chain’s department stores. Price found Golden through French Quarter art dealer Larry Borenstein and purchased nearly 50 of Golden’s paintings for his Sears Roebuck collection.

In the late 1960s and 1970s, some of Golden’s other paintings drew on the Civil War and decaying southern plantations for inspiration. His “Demolition by Neglect” series lamented the loss of some of New Orleans’ historic buildings to the modern construction boom hitting the city at that time.

In 1976, Golden was chosen to exhibit 51 of his paintings in Russia, a first for an American artist. The paintings toured the country for a year and Golden and his wife were invited as guests of the Soviet Union for two weeks, including for the grand opening of his show in Moscow.

In the 1980s and 90s, Golden continued painting and exhibiting his works all across the country, receiving dozens of awards for his work. In 2005, he was featured in a book by John R. Kemp, “Rolland Golden: Journeys of a Southern Artist.” A second book by Kemp, “Katrina: Days of Terror, Months of Anguish,” was released in 2007 to coincide with an exhibit at the New Orleans Museum of Art.

By that time, Golden and his wife had moved to Natchez, Mississippi, where he later opened a gallery. In recent years, his wife Stella became his business manager, while daughter Lucille was integral in his marketing and promotions. “That’s sort of Rolland’s secret weapon,” said John Bullard, director emeritus of the New Orleans Museum of Art. “An artist really doesn’t have time to create the work and then promote it and publicize it himself. It is often the spouse who takes on that role and Stella is a master at it.”

In 2014, Golden, who had moved to Folsom, Louisiana because of health issues, released his memoir, “Rolland Golden: Life, Love and Art in the French Quarter.” It was accompanied by an exhibition at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art.

In addition to his wife Stella and daughter Lucille, Golden is survived by another daughter, Carrie Golden Lambert; a son, Mark Damian Golden; a brother, Brother Neal Golden, C.J.; four grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

Funeral arrangements are pending.