NEW ORLEANS — Leah Chase, the beloved “queen of Creole cuisine” whose Dooky Chase’s restaurant in Treme served two U.S. presidents and stood as a landmark of the Civil Rights era, died Saturday, June 1. She was 96.

"While we mourn her loss, we celebrate her remarkable life and cherish the life lessons she taught us," said the Chase family in a statement Saturday.

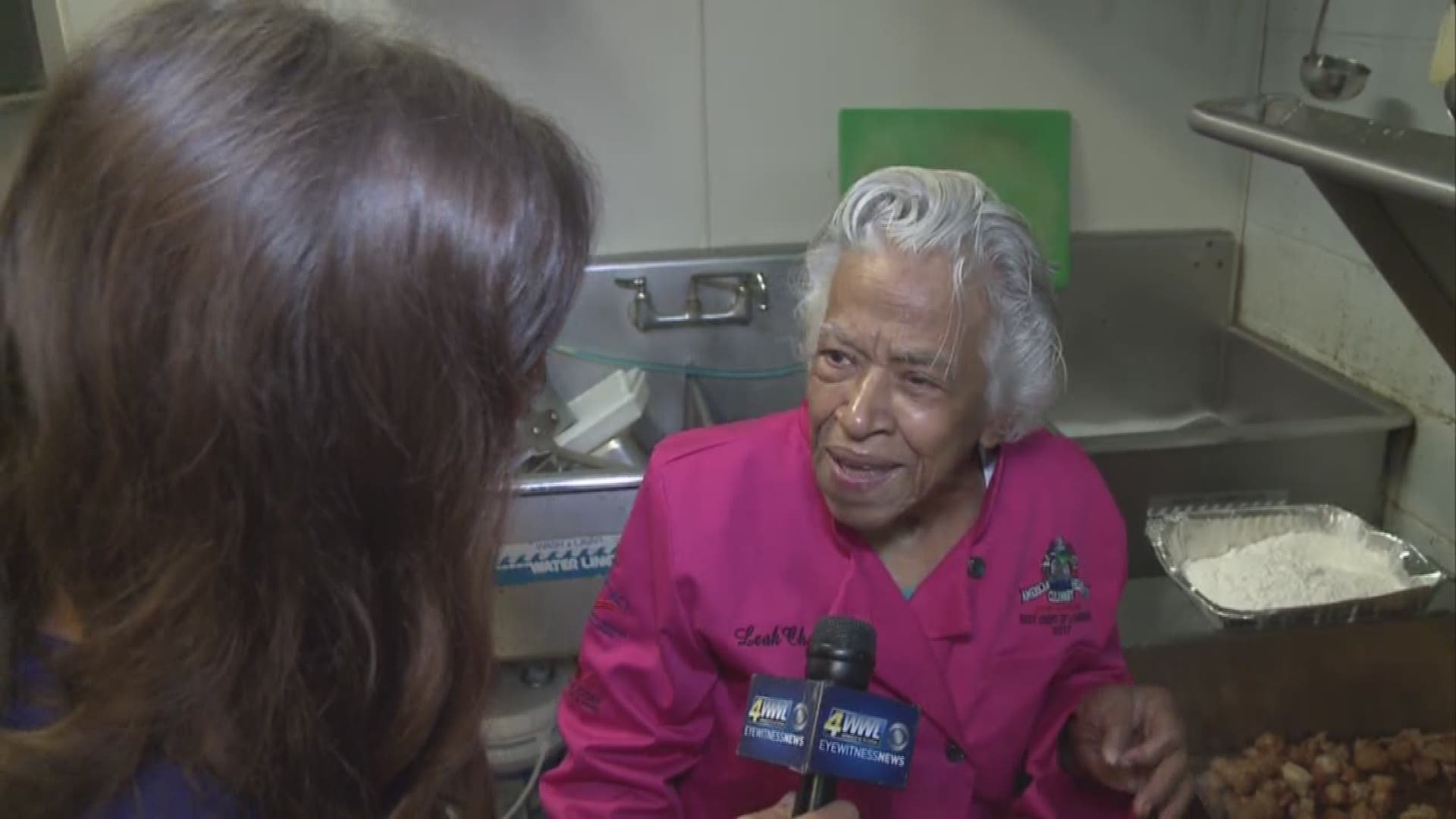

Even well past her 95th birthday, Mrs. Chase showed little signs of slowing down, preferring instead to stay busy in the kitchen of her Orleans Avenue restaurant, preparing the food at Dooky Chase’s, which has served the neighborhood and visitors for more than 75 years.

“I love what I do. If I wouldn’t come in this kitchen every day, I think I would be miserable,” she said during a 2018 WWL-TV interview with Sally-Ann Roberts. “My children say, ‘Why don’t you stay home?’ Nope! I don’t want to stay home. I want to do what I do,” she said. Doing so earned her accolades and awards from across the country for her contributions to the culinary world and to the community.

The Chase family made the announcement late Saturday evening, bidding farewell to who they called "a strong and selfless matriarch."

"She was a major supporter of cultural and visual arts and an unwavering advocate for civil liberties and full inclusion of all. She was a proud entrepreneur, a believer in the Spirit of New Orleans and the good will of all people, and an extraordinary woman of faith," the family said in a statement.

In 2016, she traveled to Chicago to accept a lifetime achievement award from the James Beard Foundation.

Story continues under image

“Madisonville, just look at me now! A long way from the strawberry patch,” Mrs. Chase said, referencing her hometown. “I don’t know how I got here, but this gives me courage to keep going. I’m 93 years old … and this gives me courage to keep going for about 10, 12 more years.”

During the awards ceremony, Mrs. Chase’s restaurant was hailed as a landmark not just in the food world but also the Civil Rights movement.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Mrs. Chase and her family hosted lunch and dinner meetings for Civil Rights leaders such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, Thurgood Marshall, The Freedom Riders and dozens of local activists.

“I fed them gumbo and fried chicken and they met here. We gave them space to meet,” Mrs. Chase said in 2018. “Nobody ever bothered them. Never, ever did a policeman come inside of this restaurant.

Dooky Chase’s was also noted as a place where even during segregation mixed race groups could meet during lunch or dinner.

Story continues under video of Ms. Chase preparing Gumbo Z'herbes

“Everybody who came to New Orleans, we were the only place that you could go, so we fed everybody,” she told Angela Hill in a 1990 WWL-TV interview. “We fed baseball players, basketball players. And I guess we had integration before integration existed. Some of these walls could tell you big stories.”

Those stories from Dooky Chase’s would also include tales of political dealmaking, with her restaurant a frequent dining spot for power brokers and politicians. Among them was the city’s first African-American mayor, Ernest “Dutch” Morial, who would host wild-game dinners at Mrs. Chase’s restaurant each autumn, during which she would prepare ducks for upwards of 650 men.

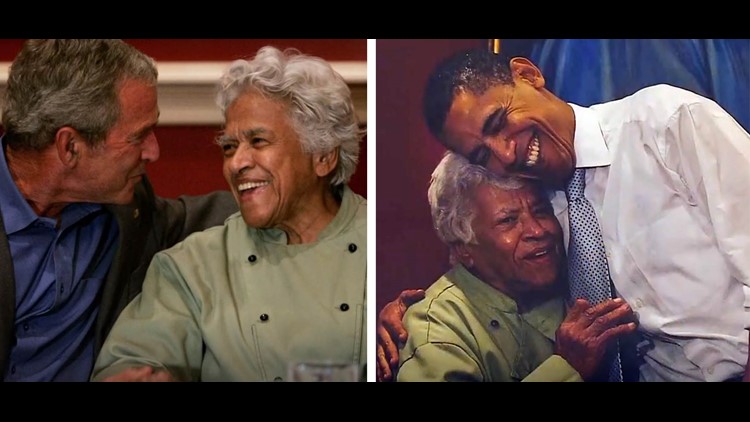

Mrs. Chase served two U.S. Presidents at her restaurant: George W. Bush and Barack Obama.

“The culinary industry is really marvelous, because I don’t care if you’re the pope or the president, you have to eat,” she said in May 2016 at the James Beard award ceremony. “Poor Mr. Obama, we had a fight the first time (she served him). Mr. Obama from Chicago, what do you know about gumbo? Nothing!” she joked. She famously teased the president for putting hot sauce in her gumbo. She also cooked for President Bill Clinton at an event in Atlanta.

Story continues under video

Other notables who dined at Dooky Chase’s and sang Mrs. Chase’s praises over the years included Duke Ellington, Nat “King” Cole, Sarah Vaughan, Lena Horne, Count Basie, The Jackson 5, Quincy Jones and many others. Ray Charles even sang about Dooky Chase’s in his version of “Early in the Morning,” released in 1961: “I went to Dooky Chase's to get something to eat/The waitress looked at me and said, ‘Ray, you sure look beat.’”

Born Leah Lange on Twelfth Night – Jan. 6 – 1923 and raised in Madisonville, Louisiana, Mrs. Chase was one of 11 children in a Catholic Creole family. In 1937 she moved to New Orleans to live with an aunt to attend St. Mary's Academy, then located in the French Quarter, for high school.

“My father was so Catholic and there was a public school near us but he always wanted us to go to Catholic schools, so we had to come to New Orleans,” she said in 1990.

After completing high school, Mrs. Chase had a colorful work history, including her first job at a French Quarter laundry. “I had to have a job or my daddy wouldn’t let me stay in the city,” she explained.

Story continues under photo gallery

Remembering Leah Chase

She later managed two amateur boxers and worked for a bookie. Her favorite job, though, was waiting tables for $1 a day at the Colonial Restaurant on Chartres Street and The Coffee Pot on St. Peter Street in the French Quarter. Though she said she enjoyed working in restaurants, she actually hated to cook.

In 1945, Mrs. Chase, then 23, met and married 18-year-old musician Edgar "Dooky" Chase Jr., whose parents owned a street corner stand that sold sandwiches and lottery tickets and had opened four years earlier. However Mrs. Chase later admitted theirs was an unlikely relationship.

“I never liked musicians,” she told Hill in 1990. “I just thought they were weird. I don’t know what happened there. I knew him only three months and we were married.”

They would remain married until his death in 2016.

During the early years of their marriage, Mrs. Chase spent her time raising their four children, but once they were old enough to attend school, she began to work at the restaurant three days a week. Her restaurant experience would serve her family well.

“They (her in-laws) had no restaurant knowledge as such. Black people didn’t have that in those days. They would open these little shops and sell food out of their houses to make money,” she said.

Story continues below video of Ms. Chase receiving her James Beard Award

At Dooky Chase’s, Mrs. Chase started out as a hostess, but she was soon redecorating the restaurant and working as chef. She changed the menu to include hot meals and a higher class of cuisine than African Americans at that time were accustomed to finding in restaurants or sandwich shops.

Eventually, Leah and Dooky Jr. took over the business, which had become a sit-down restaurant and a favorite local gathering place. It also became the centerpiece of Leah Chase’s life.

“My life is making other people happy. My life is feeding them good food. I love that. That’s what makes me happy,” she said in a 1995 WWL-TV interview with Bill Capo.

Inundated by floodwaters from the levee failures after Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Dooky Chase’s was closed for two years until friends, fellow chefs and volunteers helped rebuild the restaurant and get Mrs. Chase back on her feet.

Since reopening, Holy Thursday would always draw one of the biggest crowds of the year. More than 600 people would pack the restaurant for a taste of Mrs. Chase's gumbo z'herbes, a Creole gumbo made of greens and representing the last meat eaten before Easter Sunday. In recent years, Chef John Folse, a longtime benefactor and admirer of Mrs. Chase’s, would donate ingredients and staff to help prepare the special gumbo.

Even into her 90s, 16-hour days at work in the kitchen were commonplace for Mrs. Chase. She would make the rounds in the dining rooms to the delight of customers, some of whom traveled cross country to experience her brand of Creole cuisine.

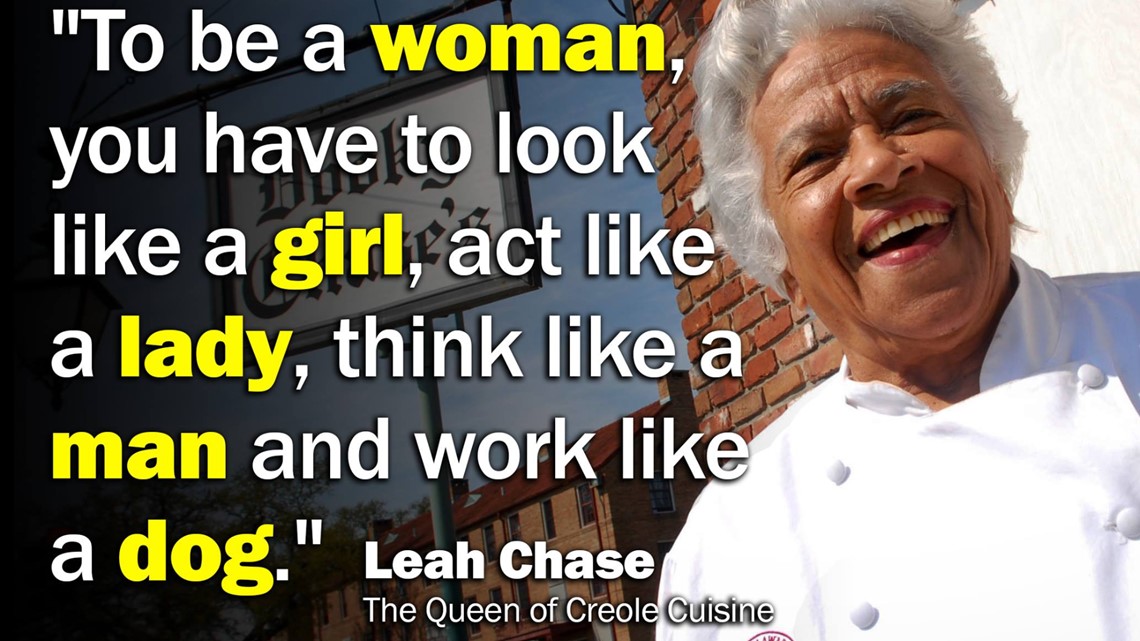

When asked about her work ethic, she often quoted her mother’s advice to her as a girl: “She always said to be a good woman you had to look like a girl, act like a lady, think like a man and work like a dog. Those are the rules I came up by and they did well for me and they will do well for any young woman,” she said in 2019.

Mrs. Chase received numerous awards both for her culinary skills and her community service, including the Times-Picayune Loving Cup award in 1997. She was named New Orleanian of the Year by Gambit in 2015.

One of her chef’s jackets is on display at the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. In 2011, a portrait of Mrs. Chase by artist Gustave Blache III was added to the Smithsonian Institution’s National Portrait Gallery. Blache, a New Orleans native, painted Mrs. Chase working in the kitchen of her restaurant, wearing a baseball cap, an apron and slicing yellow squash. The chef said she felt Blache’s painting, one of 20 he did of her at work in the kitchen and restaurant, captured her likeness.

“I told him, 'You could have made me look like Halle Berry or Lena Horne, but you made it look like me,'" she said.

Other honors she received during the years included the Weiss Award from the National Conference of Christians and Jews, the Torch of Liberty Award, the University of New Orleans Entrepreneurship Award, the Outstanding Woman Award from the National Council of Negro Women and honors from the NAACP. She received honorary degrees from Tulane, Loyola and Dillard Universities and Our Lady of Holy Cross College.

In 2009, Disney’s first animated African-American princess, Princess Tiana in “The Princess and the Frog,” was inspired by Mrs. Chase’s life.

“They made the prettiest little princess you ever saw, she’s a pretty little thing,” Mrs. Chase told Sally-Ann Roberts in a 2018 WWL-TV interview. “Little children look at that and it’s just fun to see what they think about Princess Tiana. A little blonde boy came to my kitchen one day and he looked at me, he told his mother, ‘She’s not Tiana.’ I said ‘I’m sorry, Tiana just got old!’

In 2016, Mrs. Chase made a cameo in Beyonce’s “Lemonade” music video. Mrs. Chase also appeared in a PBS cooking series and wrote three cookbooks: The Dooky Chase Cookbook, And Still I Cook, and Leah Chase: Listen, I Say Like This.

During the years, she served on the boards of many non-profits and charities including the Arts Council of New Orleans, the New Orleans Museum of Art, the Urban League and Women of the Storm. She was a featured chef for nearly two decades at the annual Chefs’ Charity for Children fundraiser benefiting St. Michael Special School.

Mrs. Chase was also a well-known patron of African American artists and her collection, displayed on the walls of her restaurant, was at one time considered New Orleans' best collection of African American art. She was an ardent supporter and board member of the New Orleans Museum of Art.

“When I first went to the museum, that was like heaven to me. I’d never been in a museum in my life,” she said. “I got all my friends who were artists and they really helped me learn more about the arts and it really warms me up. I can’t draw a straight line but they can, and I like that.”

Mrs. Chase once appeared before Congress to lobby for greater funding for the National Endowment for the Arts.

In 2013, to help mark Mrs. Chase’s 90th birthday, her family and friends launched the Edgar "Dooky" Jr. and Leah Chase Family Foundation. Its stated mission is to “cultivate and support organizations that engage in activities that support cultural arts, education, culinary arts, and social justice.”

Mrs. Chase’s firstborn daughter, Emily Chase Haydel, died during childbirth in 1990 at age 42. For many years, she was her mother's right hand in the restaurant. Since then, another daughter, Stella Chase Reese, has assisted her mother in running the restaurant and coordinating her many appearances and events.

In addition, Mrs. Chase is survived by her son, Edgar "Dooky" Chase III; and daughter Leah Chase Kamata; as well as 16 grandchildren and 27 great-grandchildren.

Funeral arrangements were incomplete.

In lieu of flowers, the Chase family asks that donations be made in Mrs. Chase's memory to the Edgar L.“Dooky” Jr. and Leah Chase Family Foundation, P.O. Box 791313 New Orleans, LA 70179.