How the promise of affordable housing lured Black New Orleans residents to a toxic waste site

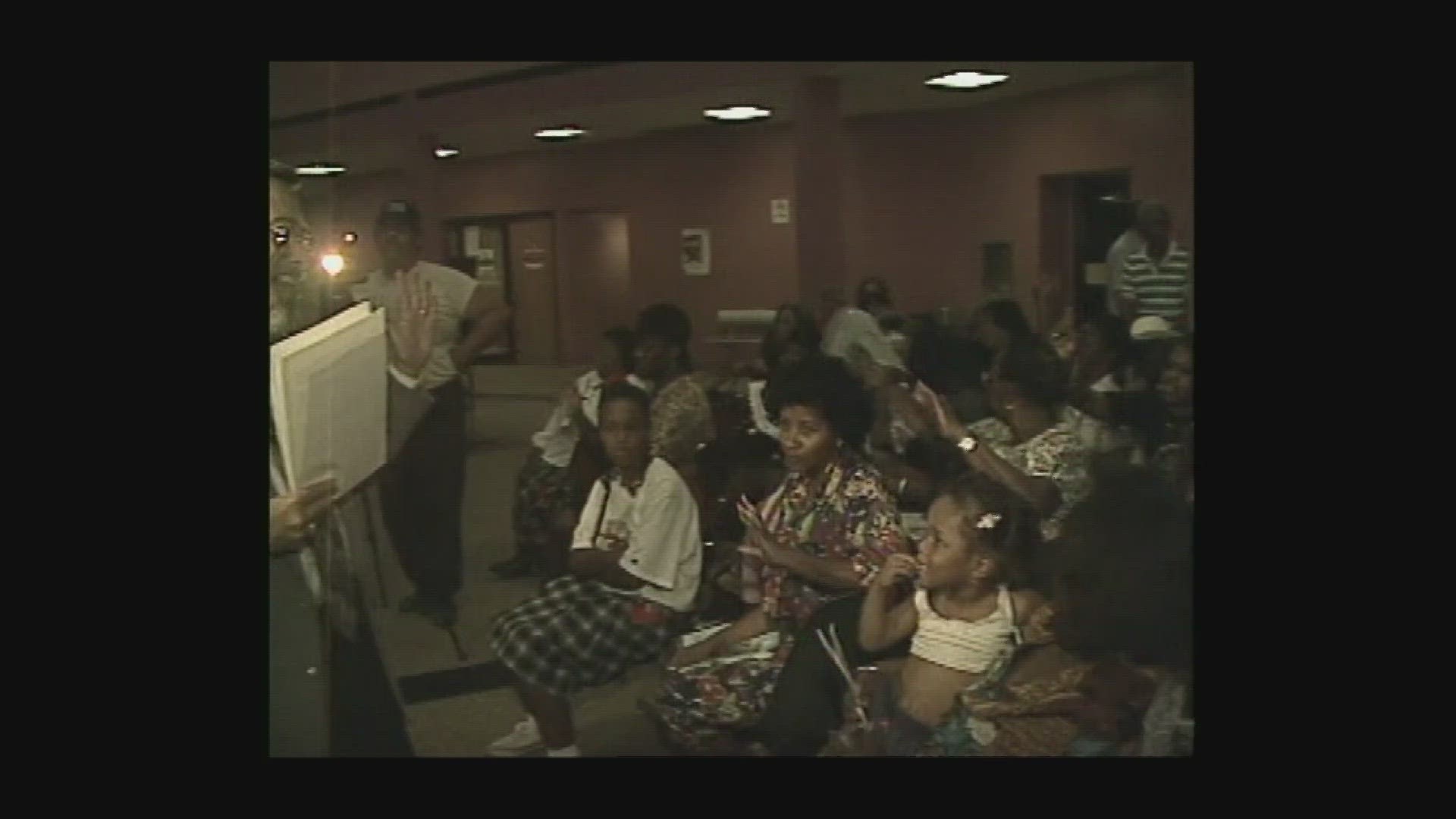

The residents still protest what they say was “environment racism” to this day at the steps of City Hall.

The Gordon Plaza Story Home ownership for low to middle income Black families

One of the most glaring examples of steering that's become infamous in New Orleans was Gordon Plaza, a neighborhood built on the site that was once the Agriculture Street Landfill.

The landfill opened in 1909 and operated for about 50 years with its initial "residents" being medical, residential and industrial waste.

After years of protests and legal action, the city closed the landfill in 1957. Before that, some city council members took a look at the dump and said it would be a great site for a "beautiful subdivision."

According to the NOLA Dater Center, by the time the subdivision was under construction, the poverty rate for Black people in New Orleans was at 37%.

With the lack of affordable housing and discriminatory housing practices, the steering of Black residents to Gordon Plaza was easy.

“Neighborhoods were built on top of hazardous waste sites. Under current EPA laws it's illegal but it wasn't always illegal,” said Dr. Robert Collins, Professor of Urban Studies and Public Policy, Dillard University. “The EPA regulations that prohibit building houses on hazardous waste sites are relatively recent, just in the last couple of decades.”

It's been 29 years since the EPA designated the Agriculture Street Landfill....a superfund site. The site contained the Press Park Apartments, Moton Elementary School, a senior housing complex and the Gordon Plaza community.

The residents still protest what they say was “environmental racism” to this day at the steps of city hall. They are demanding a fully funded relocation from their homes.

“A lot of the times a lot of these hazardous waste sites were old sites from the 30s, 40s and 50s,” Dr. Collins said. “The waste was buried. They were paved over. It might have been a vacant piece of land for 10 or 20 years and then a developer decides to build a housing development.”

Jesse Perkins bought into the idea of Gordon Plaza, though he somewhat knew of its past.

“Homeownership was a big deal, especially for poor black people. I mean, we didn't have a lot coming from the Desire projects,” Perkins said. "I know it was a landfill. However, I did not know it was a toxic waste landfill, which is a huge difference.”

Selling the American Dream The promise of a home was alluring

For Jesse, the chance to bid on a home that went up on the auction block in Gordon Plaza was one that meant more to him since his Mother never owned a home.

“I just wanted to make sure my mom had a place that nobody could come away and say, you know what, hey you didn’t pay this and we’re confiscating the home,” Perkins said. “The home was paid for. Paid the taxes and you’re good, you’ve got a roof over your head mom.”

Lydwina Hurst says she jumped at the chance to live inside of a new brick home.

“A lot of the people talked about being first-time homebuyers. So, this was very exciting. And not thinking at the time, all these homes were marketed not only to low-middle income families but marketed to African Americans only," Hurst said.

It was also being marketed by the city's first Black mayor.

The plan for Gordon Plaza was carried out through Ernest Dutch Morial, though he didn't initially introduce the re-imagined dump. That was the work of Councilman turned Mayor Victor Schiro. Morial did, however, push residents toward the community.

Shannon Rainey learned about the community while working as a receptionist for Dutch Morial.

“We found out they were building houses in the Desire community area,” Rainey said. “So this was exciting to me to be able to purchase a house at the price we purchased the houses at and it was a brand new construction and they were very nice.”

Poison in the Ground

Residents and environmental activists say the affordable housing came with a major cost.

Environmentalists petitioned the EPA to test at Gordon Plaza after nearby Moton Elementary School found lead contamination in the soil.

But the amount wasn't enough to meet the EPA's standards based on the Hazard Ranking System at that time, so developers simply placed new topsoil on existing soil.

Gordon Plaza residents were still concerned.

“People were very displeased because of what they were finding when they dug up their yards to plant vegetables,” Hurst said.

“Well we knew as we was digging that we would find bottles and stuff because it used to be a dump site,” Rainey said. “As we continued to dig and continue to dig in we found a can. It was a gasoline can but on that gasoline can it had a skeleton head on it that said poison.

The EPA came out again to test the soil, after a sewerage leak at the Moton school in 1993. By this time the Hazard Ranking System had changed.

The results were enough to qualify Gordon Plaza, Press Park and the Moton Elementary School as a superfund site. The Agriculture Street Landfill site was added to the National Priorities List in 1994, despite the EPA telling the community earlier there wasn't a dangerous level of pollutants.

Moton school would close soon after Hurricane Katrina.

“Not only could that developer build there without any sort of mitigation in terms of taking the waste out but that developer was not under any legal obligation to let any homeowners know what their homes was underneath,” Dr. Collins said.

After testing the site, Chemist Whilma Subra told the Louisiana Weekly: "The Agriculture Street Landfill is contaminated with arsenic, lead, and polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons ("PAHs") among more than 140 toxic materials, at least 49 of which are associated with cancer.”

Lasting Effects

Years later, many residents began to develop illnesses.

The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry found for the 10-year period, 1988-97, there was a Breast Cancer cluster for Black women living on the site, though they stopped short of linking those instances to the toxic substances found on the ground because they're tough to prove.

“There are several people around the neck in this area that have died of cancer," Hurst said. “There's a number of people, a large number of people who have been diagnosed with cancer, respiratory illness and abdominal rashes.”

A 2019 Louisiana Tumor Registry report found Gordon Plaza is within the census tract to have the second highest consistent rate of cancer in Louisiana. Lydwina Hurst is a breast cancer survivor.

Immediately after the Superfund designation, residents asked to be moved.

Instead, the EPA did remedial work cleaning up and removing some of the soil, putting down a geotextile barrier and topping it with new clean soil.

“We've had several lawsuits, civil lawsuits,” Hurst said. “Meeting with the politicians, you meet in with the experts, medical experts and you're meeting with attorneys, and then all of it goes by the wayside.”

We'll continue to Follow the Line throughout the year with more special reports.

► Get breaking news from your neighborhood delivered directly to you by downloading the new FREE WWL-TV News app now in the IOS App Store or Google Play.