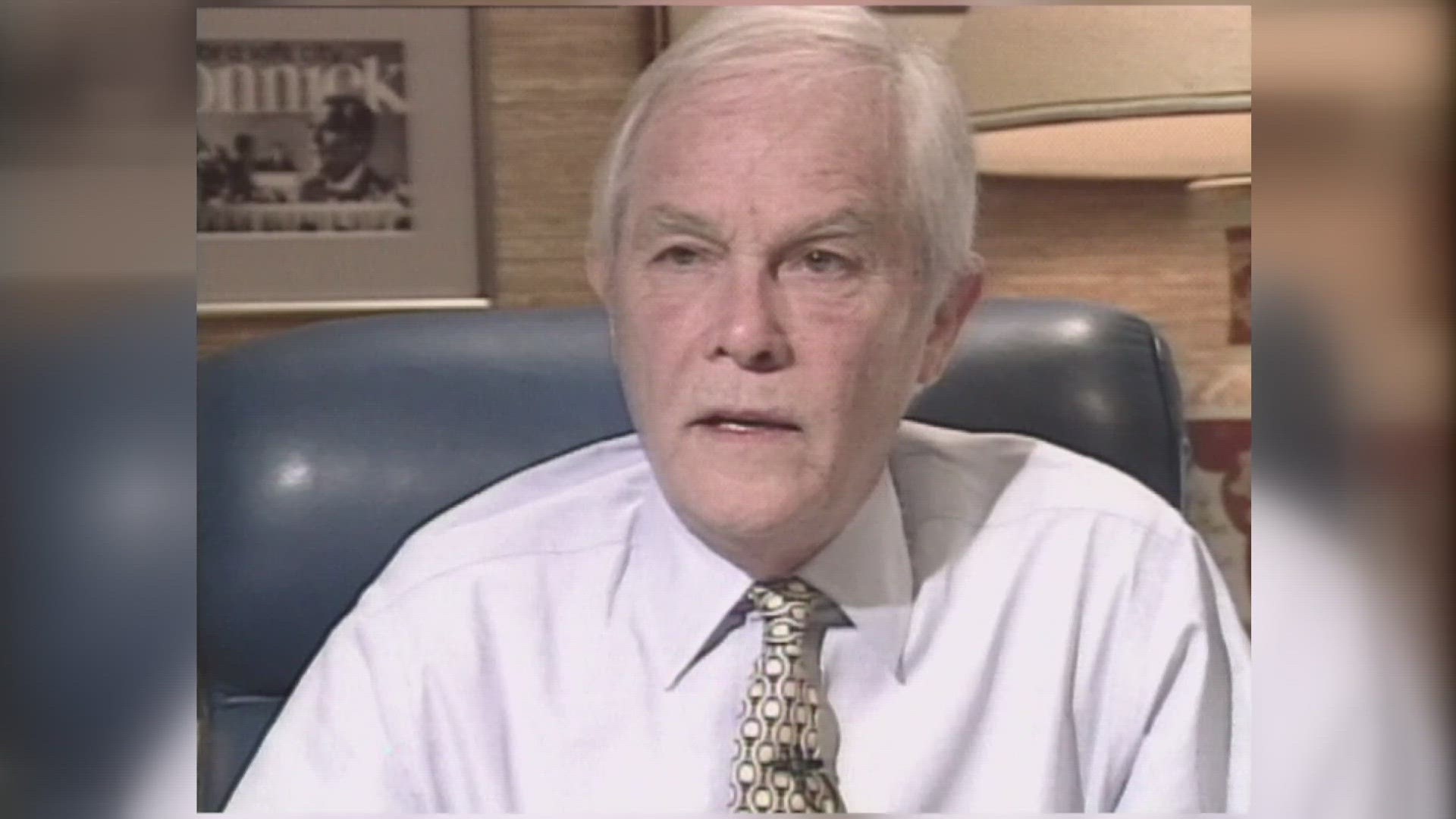

NEW ORLEANS — Harry Connick Sr., the longest-serving district attorney in New Orleans history, whose colorful and often controversial 30 years in office made him one of the most powerful but scrutinized politicians in the city, has died. He was 97.

In the flamboyant and flashy style that he was often known for, Connick stepped down in January 2003, staging a midnight second line out of his office led by his son, Grammy and Emmy award-winning singer, musician and actor Harry Connick Jr.

The elder Connick, who was first sworn in as district attorney in 1974, announced on his 76th birthday that he would step down from his post after five terms in office. "This is a sad announcement for me to make," Connick said at the time. "On Jan. 10, 2003, I will no longer be doing what I like best to do. That is being district attorney of this great city."

He was surrounded at the news conference by family, friends and supporters, as well as staff, prosecutors, and former assistants, who later became judges at Criminal District Court. That includes Judge Camille Buras and District Attorney Leon Cannizzaro as well as former judges Raymond Bigelow, Dennis Waldron, Terry Alarcon, Patrick Quinlan and Julian Parker.

Connick's start

In 1969, Connick was largely a political unknown when he waged his first political campaign, taking on District Attorney Jim Garrison. Though he had had served in the U.S. Attorney’s office, as a Legal Aid defense lawyer and an attorney in private practice, Connick lost to Garrison, the 12-year incumbent. Four years later, however, he beat Garrison by some 2,221 votes.

When he took over in 1974, supporters said Connick revolutionized the office, which had some 7,500 cases on the docket, many dating back more than a decade. “I think he came in when the D.A.'s office was in great turmoil, there was very little cooperation between the D.A.'s office and the police department, FBI and other agencies,” said Bigelow upon Connick’s retirement. “I think Harry was able to bring a lot of it together.”

Challenges to decisions

Bold and brash, sometimes combative and with the image of a reformer, Connick’s three decades in office were not without controversy. In fact, some of the cases he and his staff tried continued to make headlines, decades later.

Connick and some members of his former staff were lambasted for mishandling evidence in dozens of cases, leading to convictions being overturned or dropped based on allegations of prosecutorial misconduct. Most notably, the 1985 death sentence of John Thompson was overturned because of prosecutorial misconduct. The U.S. Supreme Court later absolved the District Attorney’s office of a $14 million judgment in the Thompson case, saying the office could not be held liable for failing to train prosecutors to turn over evidence based on a single case.

His office made decisions that were challenged by the Innocence Project, and, according to a 2012 story in the Times-Picayune, that organization said that Connick’s number of overturned convictions based on allegations of misconduct, numbers “in the dozens.”

Connick, in the same article, defended his record, while admitting he wasn’t perfect.

"My reputation is based on something other than a case, or two cases or five cases, or one interception or 20 interceptions. Look at the rest of my record. I have more yards than anybody," Connick said.

"Would you make it the legacy of Hank Aaron or Babe Ruth that they struck out a lot?" he went on. "I have to look at myself and say this is who I am. This is what I've done. Perfect? No. But I've done nothing to go to confession about in that office. At all."

There was also the 1995 Supreme Court reversal of Curtis Kyles’ conviction in the 1984 killing of Delores "Dee" Dye. Kyles spent 11 years on death row before the Supreme Court threw out the case because of prosecutorial misconduct.

Connick steadfastly defended the actions of his prosecutors, maintaining a tough stance against violent crime, and saying that the sheer number of trials clouds their record. His office handled some 2,200 trials during the last five years of his tenure, equaling more than a third of all criminal cases tried in Louisiana during that time. "Keep in mind, too, there are 1,000 cases and convictions sustained," Connick told The Times-Picayune in a 2003 story. "Don't judge me by the exceptions."

Connick also drew fire from defense attorneys for his frequent resistance to plea bargaining. “We don’t do a lot of plea bargaining with your rights and your interest and your safety,” he told supporters at one of his re-election kickoff events.

He also tussled frequently with judges with whom he disagreed, and was known as a politician who spoke his mind, which earned him supporters and his share of detractors. An example came in a news conference he held with his successor, Eddie Jordan, in 2003. “This city is pretty damn stingy when it comes to the needs of this office and the needs of law enforcement and the courts,” he said, when asked what Jordan’s biggest challenge would be.

In 1990, Connick found himself on trial. He was acquitted by a federal jury of racketeering charges that accused him of wrongly returning seized records to a bookie.

Towards the end of his career, he took a strong stand against illegal drugs, and advocated drug testing in schools. “That's our big, serious social problem in this country. It is the terror of this country,” he said of illegal drugs, in a 2002 interview.

Connick's life before DA

Though his name loomed large in New Orleans politics, Joseph Harry Fowler Connick was actually a native of Mobile, Alabama. One of eight children, Connick’s father was transferred to New Orleans for a job with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers when his son was two years old.

After graduating from high school, Connick served in the U.S. Navy in the Pacific Theatre during World War II. Connick met his first wife, Anita Livingston Connick, after he left the service and was working for the Corps of Engineers in Morocco. After they moved back to New Orleans, they put themselves through Loyola University and Tulane University law school by running a record shop – Studio A – on Marshall Foch St. in Lakeview. Anita Connick died in 1981.

The Connicks had two children: a daughter, Suzanna; and a son, Harry Jr., who was a musical prodigy and made headlines even as a young boy. In an interview with Angela Hill, Harry Connick Sr. recounted the young singer’s early musical training.

“I was concerned about Harry leaving for New York, so I sought out the help of Ellis Marsalis. Harry had just turned 18 and had finished NOCCA and was studying at Loyola. I was apprehensive about him going to New York. But Ellis gave me good advice. He said it’s time for him to go. We knew he was a talent but could he do it?”

“So Harry came to the house and he said, ‘Pop, I really want to go to New York,’ and I said fine, you can go. He said, ‘But I want your blessing.’ I said ‘You have my blessing.’ He said ‘Well, what will I live on?’ I said, ‘It sounds like you want more than my blessing,’” the elder Connick laughed.

As his son’s musical career exploded in the 1990s, the elder Connick embarked on his own singing career, performing his big band act in local clubs and cabarets and even recording albums.

“I’ve been able to work in singing, which I love to do, and so it evolved into a regular thing for me and so I do it on a regular basis with Jimmy Maxwell and in other clubs in town,” he said in an interview.

He and his son helped form the star-studded Orpheus Carnival krewe in 1993, bringing celebrity friends to town to ride in the annual Lundi Gras parade.

Described by Time magazine as “The Singing District Attorney,” during his 30 years in office, Connick became a major powerbroker in local politics and his endorsement of a candidate or disdain for a judge or fellow member of the judicial system carried weight.

“When he wants to get involved in something, he gets really involved. He is very high profile, like if he gets in a disagreement with a judge, you know it,” said former Loyola University political science professor and WWL-TV political analyst Ed Renwick in a story to mark Connick’s retirement.

Politically, Connick benefitted from years of endorsements from the Morial family, and the LIFE political organization founded by former Mayor “Dutch” Morial and later headed by his son, Mayor Marc Morial.

Two of his nephews, Jefferson Parish District Attorney Paul Connick Jr. and state Rep. Patrick Connick, followed him into public service. His brothers, Paul Connick Sr. and William “Billy” Connick were also very involved in political circles on the state and local level.

In addition to his son, daughter and several grandchildren, Connick is survived by his wife, Londa.

Funeral arrangements have not been announced at this time.

► Get breaking news from your neighborhood delivered directly to you by downloading the new FREE WWL-TV News app now in the IOS App Store or Google Play.