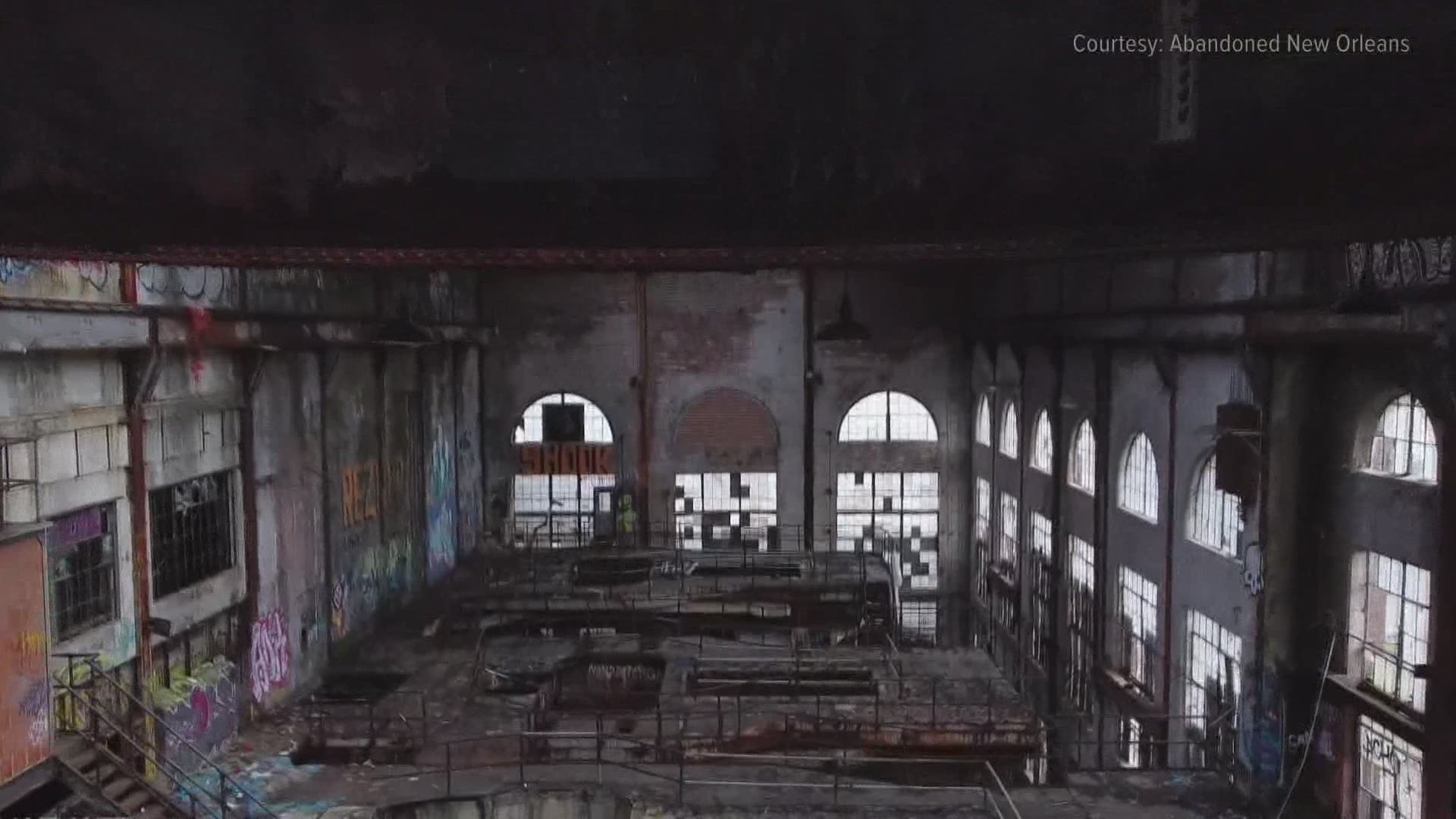

NEW ORLEANS — The Market Street Power plant is known for its towering twin stacks that stand out along the New Orleans riverfront.

It’s also known for the number of times plans to revive it have come and gone, leaving it to slowly crumble. Inside, the rusted bones of the building are accented by colorful graffiti, sprayed on over the years by those who dare to go inside.

The Market Street Power Plant, which once produced all of the power for the city, has been silent since the 70s when NOPSI, the predecessor to Entergy, shut it down.

A possible new owner, made up of several local developers, hopes to revive the building as part of a bigger plan to build a new neighborhood on the Uptown side of the Convention Center. It’s not an easy proposition.

John Williams is an architect who’s worked for some of the biggest developers in town on some of the city’s most prominent landmarks: everything from the Fair Grounds to the Ritz-Carlton to the Circle Food Store. Designing the future of the Market Street Power Plant could be his next job if the sale goes through.

He says the bigger a project, the more issues there are to deal with.

“Take the power plant. You know, it has multiple levels. It’s on the river. The zoning is constantly changing,” he said. “You have to, you know, look at doing its own zoning of, you know, planned unit development. Or then the financing. How do you finance something like this? It’s not, you know, one or two or five million dollars. It’s 50 or 100 or $150 million.”

That financing is another complex aspect. It’s known in the industry as “synthetic equity.”

“That’s like the tax credits or a break on your property taxes,” Williams said.

More recently, Williams says, the COIVD-19 pandemic has driven up construction costs.

“If you want plywood it’s several more times than it used to be,” he said.

He points to one project, finally under way, as an example of how long something can take.

“Look how long it took the World Trade Center to not only get the financing, get underway, and then how long it’s taken for the construction,” he said.

Same goes for Charity Hospital, which languished for years before work began to transform it into a mix of homes, retail space and dorms for Tulane students.

Outside of the city’s commercial areas, there are pockets of vacant homes.

Neighbors in the 7th Ward were glad to see one on North Dorgenois Street finally torn down recently.

But they had one question.

“Where’s the owner of the property at?” asked Coralee Smith, who lives across the street from the now-demolished home. “I don’t know where he lives.”

Therein lies one problem for the city. When city attorneys want to tackle problem properties, there is a long legal process.

One aspect? An “extensive title research to identify every person who is an owner or has a legal interest in the property. Once defendants parties are identified, further research locates possible addresses where notice must be sent.”

Dawn Hebert has been working with the city for years to get problem properties removed from New Orleans East.

She says she understands there’s a process in place, but that it couldn’t be more bureaucratic.

“In other communities -- St. Bernard Parish, St. Tammany Parish -- we don’t see the type of blight and high grass and overgrown lots. We don’t see that in other parishes,” she said. “We are the biggest city in this state. So what is it? Why is it not being handled? We see it -- other areas, other parishes -- being cleaned up.”

One of the more prominent vacant buildings in New Orleans East is known as the CAVEMAN READER hotel, because of the graffiti sprayed across its facade years ago.

“We’re looking at colors now. We’re going to have to paint the CAVEMAN and it won’t be the CAVEMAN any more,” Williams, the architect, said. “We’ll have to call it something else.”

A former Holiday Inn, it’s finally being converted into new housing.

But just across Chef Highway from that work is a partially demolished apartment complex full of high grass and rotting wood.

Hebert said she’s glad to see some progress, but she -- and others -- hope

there will be a greater push to wipe out blight on their streets as well.

“We are wanting to have a better quality of life. But, again, we cannot do it without the city’s help. And it needs to happen,” Hebert said. “I don’t know when it’s going to happen but it needs to happen.”