NEW ORLEANS -- During the heyday of his local supermarket empire, John G. Schwegmann was known for simply and clearly distilling his thoughts on any number of topics onto the back of one of his store’s brown shopping bags.

His writing also filled up a page of the daily newspaper, in ads that not only highlighted store specials but also discussed politics, world affairs and whatever else might be on his mind.

Fortunately for students of history, or those too young to have made groceries at “Swagg-man’s” (to borrow from the local dialect), author David Cappello goes a lot further than a brown bag or newspaper ad to chronicle the Schwegmann’s story. He devotes nearly 400 pages to Schwegmann, his stores and life story, in a new book: “The People’s Grocer: John G. Schwegmann, New Orleans, and the Making of the Modern Retail World.” It is a comprehensive look at a powerful populist – a man who was often controversial and eccentric, but ultimately wildly successful.

Since he died in 1995 and the store chain (overseen by his son John F. Schwegmann) collapsed and closed in 1999, Cappello writes that he fears Schwegmann’s legacy as a retail giant is fading. “Almost no one knows his story,” he writes. The book makes a strong case for Schwegmann as a retail genius (ahead of and on par, some would say, with Sam Walton of Walmart fame). His book delves deeply into the life story, successes and failures of the legendary grocer, a high school dropout turned multi-millionaire. A retailing titan and marketing wiz, he would become the local king of the large-scale grocery store, known for “low-cost, low-price, high-volume principles” and “everyday low prices,” decades ahead of Walmart.

Even those who may know little about the man himself still know a lot about his grocery stores. They’ll easily recount for you their memories of their neighborhood stores, whether in the city or the suburbs. Huge in size, the supermarkets’ product selection was mind-boggling, offering hundreds of products, from the everyday to the unusual (for example, a seafood department that included not just fish but crawfish, frog, turtle and alligator). At a time when few grocery stores sold beer, there was a 1,500-square foot liquor department in the original St. Claude store. More than just beer, the 1946 Schwegmann’s offered 200 brands and varieties of liquor and wine, including several Schwegmann “private-label” lines. Later, bars were even incorporated into some stores, which all offered huge spirits sections and products at discounted prices.

Schwegmann’s truly was more than a grocery store. There were four nonfood departments in the first store (replicated and expanded in other locations to follow): drugs and cosmetics, hardware and sporting goods, housewares and gifts, and a snack bar. Later stores added pharmacies (unheard of at the time) as well as banks, gas stations, bakeries, radio-TV appliance shops, shoe repair, barbershops and floral shops, with space leased to outside businesses to operate inside the Schwegmann’s stores. To the modern observer, it’s easy to see how practically every service or product a person could think of would be easily available at a Schwegmann store, all of which contributed to the local chain’s success. It was Walmart well before its time.

The Schwegmann story begins at the family’s original corner store at Piety and Burgundy in Bywater (above which John G. Schwegmann lived as a child), but really blossoms in 1946 when Schwegmann goes out on his own and opens the original Schwegmann Bros. Giant Supermarket at St. Claude and Elysian Fields avenues. It should be noted that the building at that original site is being returned to commerce as a Robert Fresh Market, after many years of court fights and blighted status.

Branching out from the city, Schwegmann opened his second supermarket on Airline Highway near Labarre Road in Metairie. Dubbed the world’s first supercenter, it opened in 1951 and was comprised of 84,000 square feet, “more than triple, almost quadruple, the size considered at the far edge of optimal (25,000 square feet) by conventional retail wisdom in 1950,” according to Cappello. The store featured a mammoth parking lot, which could accommodate some 2,000 cars. Schwegmann and his team introduced a new method of climate control to try to cool the cavernous building – spraying a constant stream of water on the roof of the building, with the water supplied from two wells dug on the property. While that method did help to cool the store during hot summers, there was actual air conditioning in the building, though Cappello explains it was only used in two areas: upstairs (in offices and a pharmacy storage space) and to cool the store’s bar.

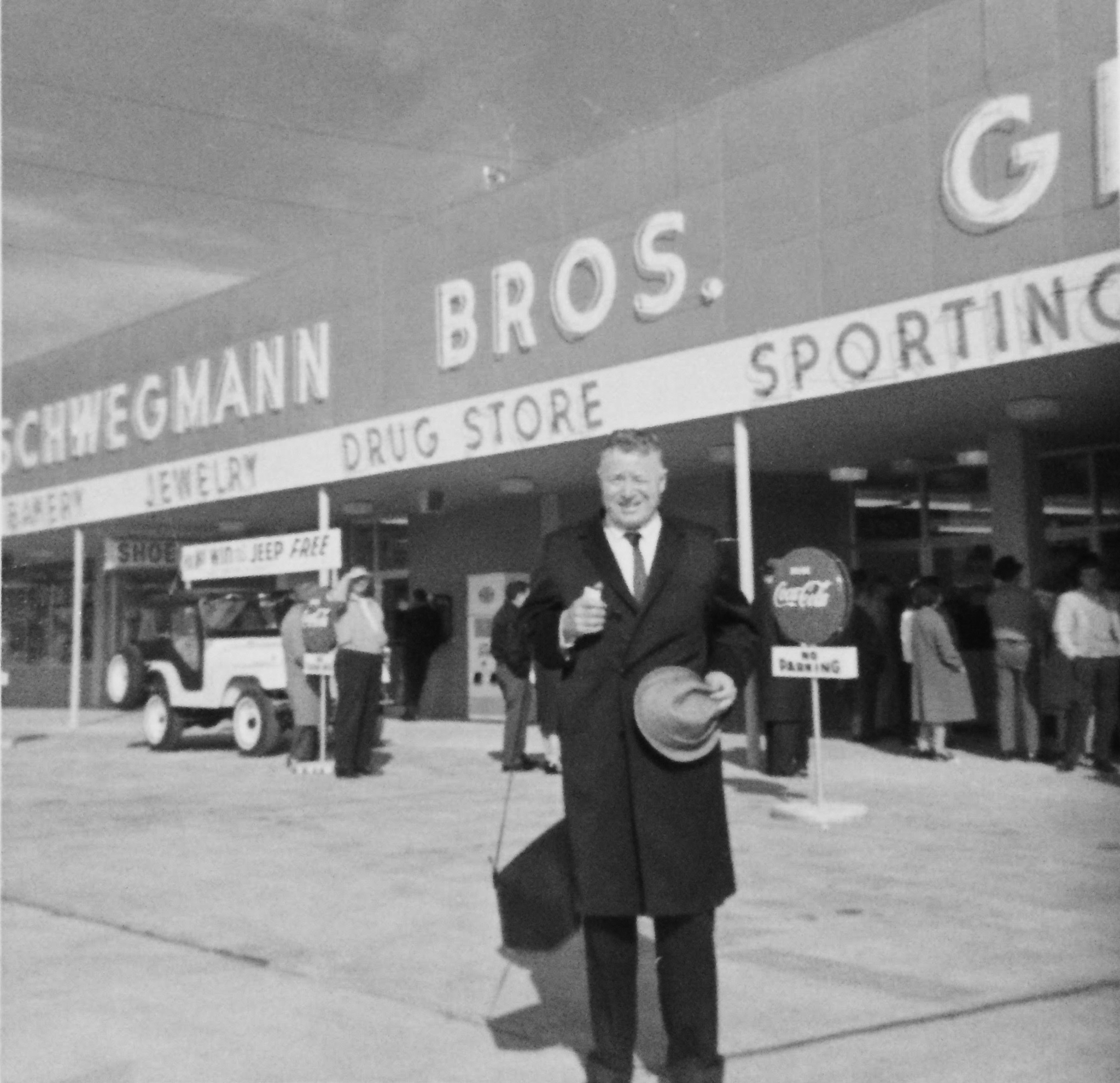

If the Airline store was big, Schwegmann’s third store, on Old Gentilly Road near Chef Menteur Highway, was truly giant – a 300,000 square foot store. It became a ‘destination’ store, with people traveling from throughout the region to shop there. There is also a fascinating chapter of the Schwegmann story associated with this store, where Schwegmann sold bonds to customers to help finance its construction. Ten-thousand bonds were issued at $100 each and snapped up by customers who now owned a stake in their store.

Besides his grocery stores, many pages in the book are devoted to the stories of John Schwegmann, the fighter. Those chapters point to Schwegmann’s populist streak, with explanations of his fight against “fair trade laws,” or price-fixing in general, as well as in the pharmaceutical, liquor and dairy industries. Cappello explains that, while hard to believe now, there was a time when discounting was “flat-out illegal,” under agreements reached or allowed between manufacturers and government. Several of Schwegmann’s legal fights to change the practice (presumably for both his own financial benefit and for the “little guy” he claimed to always represent) went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Schwegmann used his newspaper ads to offer blunt and pointed commentary on the price-fixing wars and many other issues. One 1963 ad cleverly featured Schwegmann’s supposed family coat of arms and the origin of their name, which he said came from “schweg,” a Germanic term for axe. Thus, a schwegman was an axe-man, soldier or knight. “We at Schwegmann’s are still carrying out the old tradition – protecting the people’s pocketbook, slashing prices, and waging war on the price fixers,” the ad claimed.

Schwegmann’s political fights are also chronicled in the book, including his notable 1970s campaign against the Louisiana Superdome (a fight in which he found few supporters but made waves nonetheless), and his unsuccessful runs for governor and Jefferson Parish President. He did win election to both the state legislature and Public Service Commission. He held the PSC post for five years (from 1975 until 1980), only to be followed by his son, John F. Schwegmann, who served on the commission for 15 years after his father. His wife, Melinda, is also remembered as the first female Lieutenant Governor of Louisiana. The visages of all three (and many other political candidates over the years) were featured prominently on the backs of Schwegmann’s brown paper shopping bags.

It’s clear Cappello dives into his subject’s life story with skills honed during his years as a business analyst who once authored market research studies. In the book there are lengthy, though worthwhile, discussions of the coming of age of supermarkets, as well as histories of price-fixing and fair trade laws. But throughout the book, he also aims to paint a personal portrait of the man and his family, which includes his children (two of whom cooperated with the author by granting interviews and the use of archival photos), as well as two divorces, love affairs later in life and even his pets (who were also featured in some of his ads).

Even for those who may know some of his life story, the book does bring surprises. Though he had “genealogical roots in the grocery store business,” beginning with relatives who established the first proper grocery store in New Orleans in the 1860s, young John G. Schwegmann was urged to find another career. Instead, his uncle explained to the young man that it would be in his best interest to get a job somewhere else to learn different ways of doing business. Before settling in real estate as his first career, young Schwegmann attended Soule Business School, worked for a bank and in sales for a margarine company. He also went to Moler Barber College, following the advice of his aunt who said that since “hair always grows,” he would never be out of a job. He never was, but it wasn’t as a barber.

After reading “The People’s Grocer,” it’s hard to imagine John Schwegmann as anything other than a supermarket superstar. But the name you know belongs to a man about whom you probably don’t know the full picture. David Cappello’s book aims to change that. And retailing at $20, it’s a bargain too.

John Schwegmann would approve.

-----

David Cappello will discuss and sign copies of "The People's Grocer" on Saturday, July 8 from 2-3 p.m. at the Southern Food and Beverage Museum, 1504 Oretha Castle Haley Blvd. Free with museum admission.

He will also discuss the book on Thursday, Aug. 31 at 7 p.m. at the Jefferson Parish East Bank Regional Library, 4747 W. Napoleon, Metairie.

Photo of grand opening of the Gentilly Schwegmann's store is courtesy The Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, acc. no. 1994.94.2.1663.