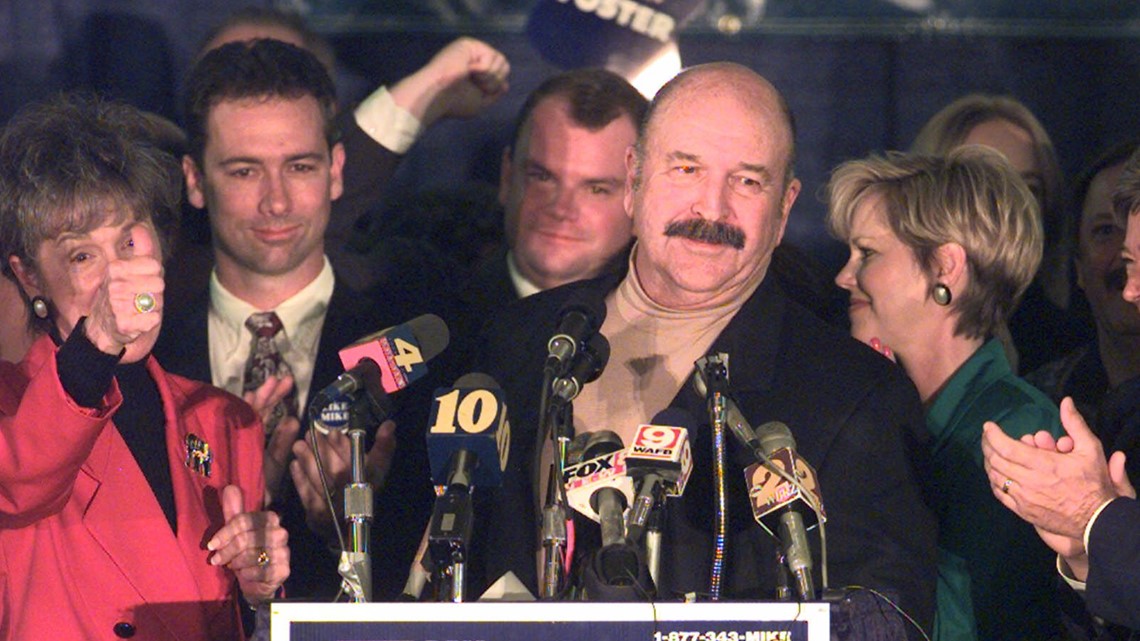

NEW ORLEANS — Mike Foster, who rode a wave of popularity as a plain-speaking conservative businessman into two terms as Louisiana governor, has died. He was 90.

His former spokeswoman, Marsanne Golsby, confirmed the news to WBRZ-TV in Baton Rouge.

When Foster entered hospice care for undisclosed health problems last week, Gov. John Bel Edwards asked for prayers for him and his family. In a statement Sunday, Edwards called Foster "a true Louisianan who served his country, his state and his community with honor throughout his life."

The former governor and his wife Alice had stayed largely out of the spotlight since he left office 15 years earlier.

His absence did not come as much of a surprise for those who observed Foster during his two terms as governor from 1996 to 2004. He showed little interest in many of the ceremonial or public aspects of the job and shunned travel, preferring to spend more time at home at his Franklin, La. plantation or hunting in a duck blind. His critics often called him out for it.

"That is a false issue," Foster told Times-Picayune reporter Ed Anderson as he prepared to leave office in 2003. "I said when I ran for office, if you want someone to cut a ribbon, I’m not going to do that. It is ceremonial B.S. I ran government, and that’s really what it is all about."

Foster, a balding, bearded bear of a man, had a blunt speaking style and conservative, pro-business philosophy which endeared him to many Louisiana voters. Most of them had never heard of him before he qualified for governor.

He had served two terms in office as a Democratic state senator from St. Mary Parish but was a virtual unknown in other parts of the state when he switched party affiliation and qualified as a Republican to run for the state’s top job in 1995.

Pundits and polls didn’t give him much of a chance, but his folksy, no-frills campaign caught on. “We don’t do a lot of strategizing,” Foster said of his campaign. “I’ve never looked at politics as that complicated. It’s the art of getting out what you believe in.”

Television campaign commercials produced by Roy Fletcher showed the multimillionaire businessman welding, farming, hunting and driving a tractor “and looking comfortable doing it,” wrote Times-Picayune political columnist Iris Kelso in 1995. “He looked like a regular working man. It appealed to people who were looking for a candidate they could identify with.”

The TV commercials featured close-up shots of Foster speaking about issues in the campaign and ended with the memorable tagline, “He’s not just a pretty face.”

“Whoever heard of a bald, overweight candidate with a mustache making it in this era of television?” Kelso wrote. “But voters are longing for something real. A proven conservative, like Coke, he was the real thing.”

In the primary, Foster led a field of fifteen candidates which included state treasurer Mary Landrieu, former Gov. Buddy Roemer and state Sen. Cleo Fields. Foster made the runoff against Fields, a Democrat.

Despite promises from both Foster, who was white, and Fields, who is Black, that neither man would make race an issue in the campaign, there were allegations of race-baiting among their supporters. Votes were cast largely along racial lines, with Foster defeating Fields by more than 400,000 votes in the runoff.

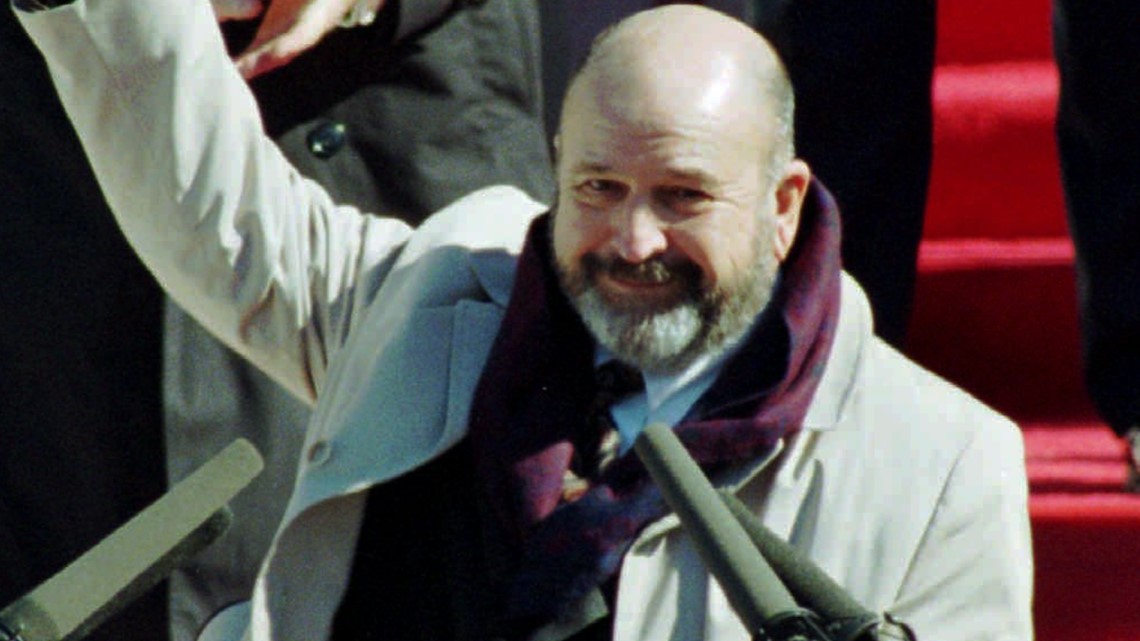

When he took the oath of office in Jan. 1996, Foster broke with 60 years of tradition by holding his inauguration on the steps of the Old State Capitol, rather than the State Capitol built in 1932 by Gov. Huey P. Long.

Foster delivered his inaugural address near the same spot where his grandfather, Murphy J. Foster, was sworn in after being elected governor in 1892. A staunch segregationist whose major campaign issue was killing the corrupt Louisiana lottery in the 1890s, Murphy J. Foster served two terms in office as governor and 12 years as a U.S. Senator.

Foster acknowledged the past in his inaugural address, but also looked to the future. “We must reinvent this government. It must be an honest government, a government that serves and a government that stays off your back and out of your pockets,” he said.

As governor, Foster was unorthodox – for example, showing up for work his first day at the State Capitol in hunting cap and work clothes. Still, supporters credited him with restoring integrity to state government, by limiting patronage and avoiding scandal, something his predecessor, Edwin Edwards, did not.

"The most important thing is we changed the whole culture of doing things, not based on politics," Foster said in 2003. "We don’t have to worry about how somebody’s brother-in-law was getting a good deal."

Foster is also credited with stabilizing state finances and beginning the work of repairing the state’s chronically poor education system. As governor, he gave elementary and secondary school teachers pay raises in six of his eight years in office, totaling about $400 million a year. He fully financed the state program that funnels money to local school boards for classroom needs, beefed up college admission standards and made TOPS scholarships available to college students.

He also created a board to develop a better technical and community college system and put more than $1.7 billion into university and college pay raises, construction and maintenance programs while protecting higher education from budget cuts.

"As governor, one of his most lasting legacies is in education, especially his support for the creation of the TOPS program, which, more than 20 years later, still helps thousands of Louisiana students attend colleges and universities and achieve their goals," Edwards said Sunday. "Gov. Foster recognized that there is no greater gift to our state than a bright future for its young people and that not everyone has to travel the same path to achieve a quality education. That’s why he created the Louisiana Community and Technical College System."

In the New Orleans region, Foster’s legacy includes sealing deals with owner Tom Benson to keep the New Orleans Saints in the city, as well as creating a package to lure the NBA’s Charlotte Hornets to town. Now the New Orleans Pelicans, the team moved here to play in the New Orleans Arena, which was completed and opened during his administration.

Foster is also remembered for pushing for an expansion of the Ernest N. Morial Convention Center and for rescuing Harrah’s New Orleans casino from bankruptcy.

Members of his administration, including chief of staff Steve Perry and commissioner of administration Mark Drennen, were key in all of those deals and other policy initiatives. Another of Foster’s hires was 24-year-old Bobby Jindal, whom Foster picked in 1996 to run the state Department of Health and Hospitals. Foster called the selection “unorthodox” but called Jindal “a genius.” He went on to serve in the George W. Bush administration and was later elected to Congress and two terms as governor of Louisiana.

Despite his successes, critics questioned Foster’s energy in pursuing economic development, mentioning his lack of interest in traveling out of state to cut business deals and court potential investors. They also criticized him for taking a soft stance on the expansion of legalized gambling, since he had campaigned as an anti-gambling candidate.

Foster, an avid motorcyclist, made headlines in 1999 when he pushed state lawmakers to make it legal for adults to ride without a helmet, calling it a

“freedom of choice” issue. The legislature approved the change, but after motorcycle deaths increased, the helmet requirement was reinstated by Foster’s successor, Gov. Kathleen Blanco.

Foster ignited controversy just days after taking office in 1996 by ordering an end to the state’s affirmative action programs for minority and female contractors. The move set off demonstrations and a march on the Governor’s Mansion by Black groups. Two major events, the Essence Music Festival and an Urban League convention, threatened to pull out of New Orleans. The New Orleans hospitality community rallied around Essence and Foster made concessions in the state's policy.

The governor faced criticism in 1999 when former Ku Klux Klan grand wizard David Duke revealed Foster paid him $152,000 for a mailing list of Duke’s supporters during the 1995 gubernatorial campaign. Duke had dropped out of the race shortly after the payoff, but both men denied the purchase was a payoff.

While the act was not illegal, Foster was fined $20,000 by the state ethics board for failing to report the deal. Foster said he believed he was not required to disclose the expense on campaign finance reports because he never used the list in his campaign. The issue was later also examined by a federal grand jury. No charges were filed against him and Foster later called the purchase a mistake and “bad judgement.”

The Duke revelation came on the eve of Foster’s 1999 re-election bid and prompted some to call him racist. In the end, Foster won in a landslide, with a primary victory that kept him out of a runoff against Democratic Congressman William Jefferson. The win made Foster Louisiana’s first two-term Republican governor.

Murphy James Foster Jr. was born July 11, 1930 in Shreveport but lived in Franklin most of his life. He graduated with a chemical engineering degree from LSU, worked as a roughneck for Humble Oil and served in the U.S. Air Force.

He met his first wife while stationed in southern Georgia. His first son, Murphy III, was born while he was in Korea.

Foster entered politics after a successful career as a construction company owner and farmer. By the time he ran for governor, his Bayou Sale Construction employed 200 people and grossed between $10 and $12 million annually. He said he first ran for the state legislature in 1986 when the incumbent, Sen. Tony Guarisco, wouldn’t return his phone calls.

Foster lived in a mansion on Oaklawn Manor, a former Franklin plantation which he purchased at a bankruptcy auction.

He met his second wife Alice, who like him was divorced with two children, on the tennis court. According to a 1995 Times-Picayune profile, Foster liked her so much, he hired her as a secretary. Then he married her.

Foster hosted a weekly radio show, called “Live Mike,” while serving as governor. He also earned a law degree while attending school part-time at Southern University in Baton Rouge.

His decision at age 70 to pursue a law degree drew coverage from The New York Times, which pointed out that Foster had made no secret of his contempt for the state's trial lawyers, “calling them ‘bad guys’ who played too large a role in picking judges and influencing legislation,” according to the newspaper. Still, Foster said earning a law degree was a lifelong ambition. He graduated in 2004, shortly after leaving office.

► Get breaking news from your neighborhood delivered directly to you by downloading the FREE WWL-TV News app now in the IOS App Store or Google Play.