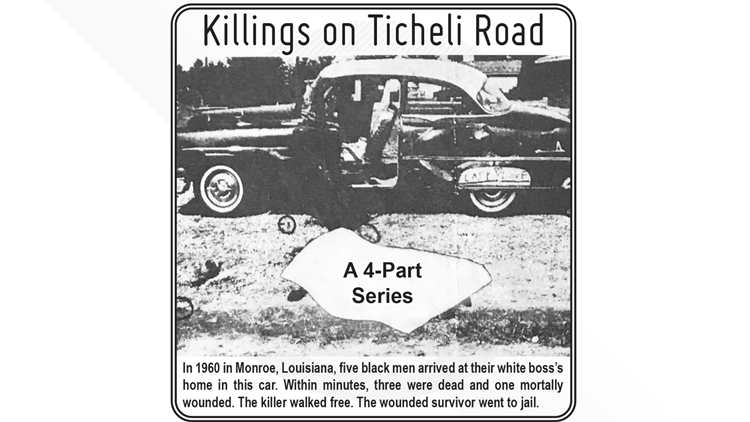

MONROE, La. — In the rural neighborhood around Ticheli Road, the sound of multiple gunshots erupted in the early morning quiet of July 13, 1960.

Sam Brooks wasn’t sure why shots were being fired, but peeking out the front window of his home, the nine-year-old looked across the street where they came from. Brooks wanted to go outside and see what was going on, but his mother kept him inside.

Nearby, 34-year-old Patricia Sherman, sleeping soundly, was awakened by her 13-year-old son. Exhausted from a late-night drive home from Arkansas, she had not heard her husband Richard, a decorated World War II veteran, leave for his job at a nearby mill.

“Mama, Mama, wake up!” her son shouted. “Mr. Fuller has shot his men.”

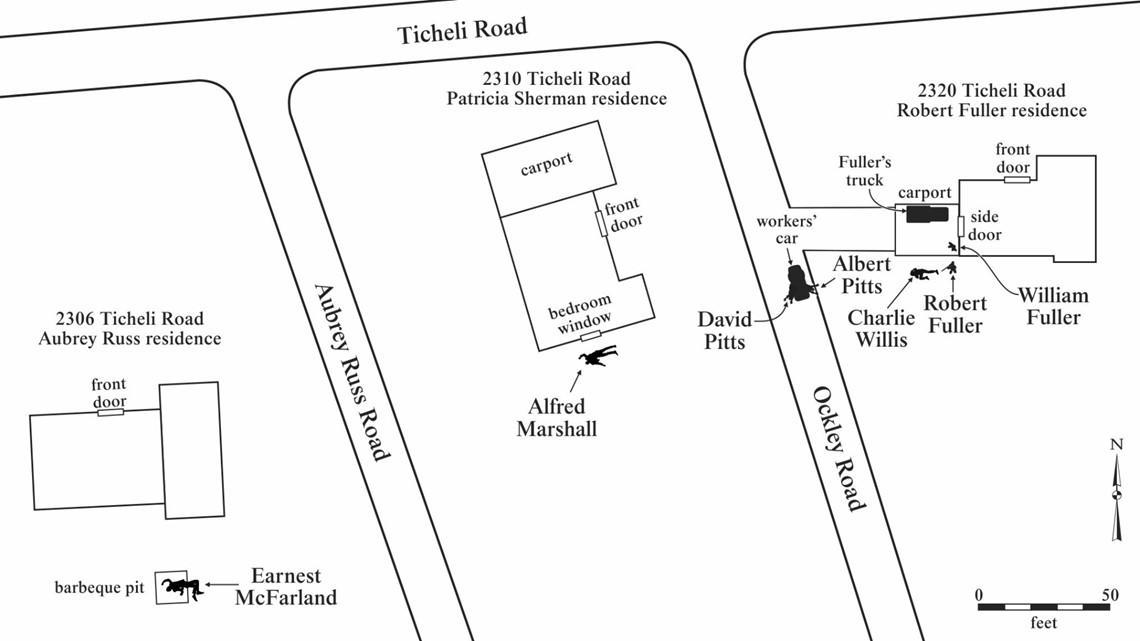

At first, Sherman told her son to let her sleep, not understanding what he was saying. But she sensed the urgency in his voice. She got up and looked out the bedroom window. Just below the sill, she saw the lifeless body of a Black man on the ground.

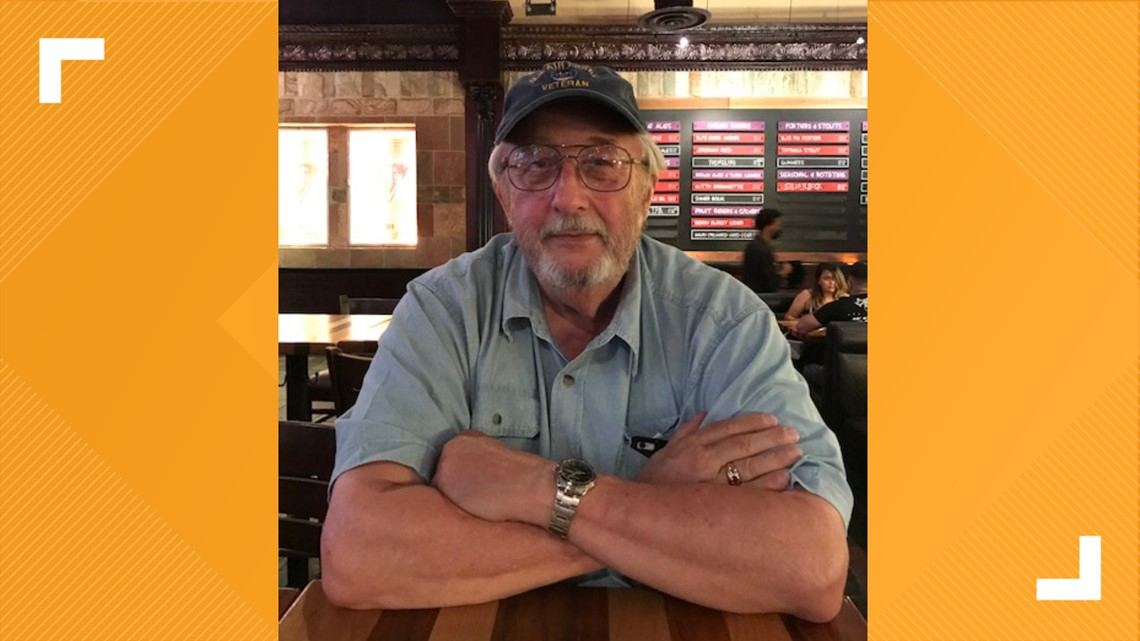

Sixty-one years later, Sherman, now 94, vividly remembers walking out onto her front porch. Less than 100 feet away, she saw her next-door neighbor, Robert Fuller, standing under his carport, and near him lay the bodies of three more young Black men. All appeared dead except one. Fuller held a shotgun over that man’s head.

Fuller’s wife was crying and screaming.

“Robert,” Sherman shouted, “what in the world is going on?”

Fuller ranted and raved and cursed the men. Pointing at a six-inch hunting knife lying nearby on the ground, he told Sherman that the men, all employees in his septic tank sanitation business, had threatened him with knives.

Fuller then instructed the lone survivor, Charlie Willis, to tell Sherman why he and his friends had come to Fuller’s home that morning.

Both Fuller and Sherman told reporters and law-enforcement officials that Willis responded: “We came to hurt Mr. Robert.”

What transpired on Fuller’s lawn at about 7 a.m. that day would go down as one of the most horrific killings of the civil rights era.

The case drew headlines from local news outlets, which primarily reported Fuller’s account and Sherman’s confirmation of what Willis said. Black newspapers from around the country reported that Fuller often cheated his employees out of their wages and owed the men money. Fuller would ride the notoriety--and his new nickname, Shotgun--to join the Original Knights of the Ku Klux Klan and eventually become its leader.

But in recent interviews, Willie Mae Pitts Sallie, a sister of two of the dead men, said that Willis told her later that the men came under attack as soon as they got out of their car, with the initial shots possibly coming through open windows on Fuller’s house. She said that Willis, who never spoke publicly about the incident, told her that Fuller threatened to kill him if he did not support Fuller’s story that the men had come to attack him.

Mrs. Sherman said she always suspected that Willis had said those words under duress. She and another witness who spoke to the FBI many years later also suggest that Fuller may have planted knives on or near Willis and the dead men to make it look like they had been armed.

And the FBI files quote the witness, whose name was redacted in the documents that the bureau released, as having “personally observed” one of Fuller’s teenage sons step out of the house with a pistol to shoot some of the wounded men.

‘IT WAS AN AMBUSH’

Sallie, also now 94, said that her brother, David Lee Pitts, had told her that one of the men had confronted Fuller the day before the shootings, saying that if he did not pay their back wages, they would call the local sheriff. According to Sallie, Willis later called David, saying that Fuller had invited the men to come to his house in the morning to get their money.

The workers pulled up on the side of Fuller’s brick ranch house in a distinctive car--a blue 1953 Pontiac Chieftain with white streaks--owned by David’s brother, Albert Pitts Jr. The words “Easy Love,” separated by a heart, were painted above the left rear passenger tire. They might have been a reminder of the Top 10 hit “Easy Lovin’” released earlier that year by R&B soul singer & pianist Wade Flemons, who would become one of the original members of Earth, Wind & Fire. Fuller claimed to the police and the press that the men called him over to talk, and when he refused, one of them swung at him with a knife. He ran to his truck and grabbed a double-barreled shotgun, he said, reloading three times and firing eight shots to fend them off as they attacked with more knives.

But Sallie said that Willis later told her that the shooting began right after the men got out of the car.

“It was an ambush,” said Charles Smith, who was nine years old when Willis, his uncle, was shot. “As soon as they walked into the yard, the shooting started.”

Smith said in an interview that after the shootings, a relative asked Willis if the men had been armed.

“Man, you know, we didn’t have no guns, no knives, no nothing,” Smith said Willis answered.

Where the men fell also calls Fuller’s account into question.

Two of the bodies were found next to the car. Another man was found unconscious and critically injured in a barbecue pit a couple of houses away. And it appears that two of the men were shot in the back.

A death certificate for Alfred Marshall, the 19-year-old cousin of the Pitts brothers, says he died of a shotgun wound to the lumbar spine, or lower back. Willis was lying on his stomach, Sherman said in an interview, and she could see the wound in his back.

Ouachita Parish Coroner Dr. John P. Burton ruled the deaths of the three who died at the scene–the Pitts brothers and Marshall--as homicides. But his reports, filed that same day, did not describe how many bullets hit them or what type most of the bullets were, details that would be standard in coroner reports today.

After the shootings, Fuller went into his house to call the Ouachita Parish sheriff, Bailey Grant, and say he had shot the men. When Grant and his deputies arrived, local press reports said, they found several knives near the bodies and one in the hand of one of the wounded men.

Sherman said she always thought that the hunting knife she saw on the ground could have been placed there by Fuller. And the FBI files quote the unnamed witness as having heard that the knives had been planted and that someone had recognized them as coming from Fuller’s house.

TWO SONS NAMED WILLIAM

The most explosive new tip came when the FBI, which had not been involved in the local investigations in 1960, began looking into the case in 2007 under congressional pressure. Congress would pass a law in 2008 calling on the bureau to examine unsolved murders from the civil rights era.

The files, which the LSU Cold Case Project obtained through the Freedom of Information Act, reveal that the FBI interviewed the unnamed individual who was at Fuller’s house that day. According to the FBI files, the witness said that Fuller was seriously behind in paying the men and that he “snapped” when they arrived that morning. An FBI agent noted in one memo that the witness “believes that if the men were white they would not have been killed.”

The witness described seeing Fuller standing with the shotgun and some of the Black men down on the ground. According to the FBI files, the witness then saw one of Fuller’s sons, 15-year-old William Herbert Fuller, step outside and shoot at least three of the men in the head with a pistol to “finish them off.”

The bureau’s main goal in examining the cases was to see if anyone was still alive who might be prosecuted. Robert Fuller died in 1987, and this son, nicknamed Puggy, died in 2005. Given their deaths, an FBI agent noted in a memo in 2010 that there was no one left to prosecute.

But one other possibility exists. Records show that Robert Fuller had two sons named William, each from a different wife. His eldest son, William Archie Fuller, was 19 then and worked in the sanitation business with the Black men.

Sherman said she saw the 19-year-old standing beside his father when she ran out into the yard right after the shooting, and she suspected he was involved. Moreover, LSU Cold Case Project researchers found a public document at the Ouachita Parish Courthouse that listed the eldest son, William A. Fuller, as a potential witness to the shootings. The document, which listed 16 other names, did not mention his younger brother, Puggy.

No direct evidence has surfaced linking the eldest son to the shootings, however, and he died in 2016. Local authorities never raised any questions publicly about whether either brother played any role in the shootings, and there is not enough detail in the coroner’s reports to tell if more than one gun was fired that day.

Sallie said Willis told her after the shootings that one of Fuller’s sons also shot some of the men. But she could not recall which son he named.

AFTERMATH

Sam Brooks, the child who heard the shots from across the street, said that his mother remembers Mrs. Sherman frantically opening their back door, knocking over a bowl of fresh peeled black-eyed peas, to tell them that Fuller had shot several people.

Brooks said his mother called his dad at work to urge him to come home to find out what happened.

Sheriff Grant arrested Robert Fuller on an “open charge,” pending further investigation to determine what, if anything, a criminal charge might be.

According to newspaper accounts, a local judge set the bond at $25,000, the highest in Ouachita Parish in a decade. Adjusted for inflation, that would be $219,000 now.

A group of men in Monroe helped Fuller make the bail, news stories said. Thirty-one hours after his arrest, Fuller walked free, waiting to see what prosecutors and a grand jury would do.

Another of Fuller’s neighbors, Beatrice Hutson, was just turning three at the time. She lived down the road from him until she was 17, and she said in an interview that she remembers hearing later that some of the men who helped Fuller would join him later in becoming members of the Ku Klux Klan.

Hutson said she also believes that local law enforcement officials took Fuller’s side.

“Mr. Fuller didn’t make no bones about it,” Hutson said. “He wasn’t scared of the law because they backed him up. They knew. There is no doubt in my mind that they knew. They covered for him.”

A few months after the shootings, Mrs. Sherman said Fuller told her something that still haunts her today–that she saved Willis’ life because he was preparing to finish the young man off when she walked onto the scene.

“It was awful,” Mrs. Sherman said.

She also said that her late husband, who had won a Purple Heart fighting with General Claire Chennault’s Flying Tigers in China, did not feel safe leaving her and their three children so close to Fuller. So they moved to another part of town not long after that.

Additional reporting by Kaitlan Darby, Rachel Mipro, Anna Jones, Evan Garrity, Karli Carpenter, Sydney Reynolds, Alaysia Johnson, Ashlon Lusk, Courtney Brewer and Bailey Williams.

Next part of the series: ‘That’s when the justice system gets flipped on its head.’

RELATED: Critical Race Theory | What is it?