Louisiana is suing nearly 4,000 residents to get back $300 million in Katrina rebuilding money

Constant rule changes meant to help homeowners after Hurricane Katrina ended up hurting those in need.

In early 2008, I sat with Paul Rainwater shortly after he was named head of Louisiana’s hurricane recovery agency and asked him how the state planned to enforce tens of thousands of separate agreements with individual homeowners who promised to rebuild and reoccupy their homes within three years in exchange for receiving federally funded Road Home grants.

He shook his head.

“That’s a very good question,” he said.

It’s a question that vexed state leaders from the very beginning of the Road Home program in 2006, and they’ve tinkered with the rules and their plans to enforce them dozens of times in the 16 years since. They were trying to show compassion for residents whose lives had been turned upside down while also complying with the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development’s demands to recover any money that wasn’t used for the prescribed purpose.

“We had 200 amendments to the plan, but there had to be because no one had ever done this before and the situation was so different than anyone had ever dealt with,” Rainwater said in a recent interview. “So, it was a very difficult time.”

Chapter 1 The Fine Print

The question of how to enforce the rules of the largest housing recovery program in American history remains difficult, and it’s no longer theoretical.

Now, under pressure from HUD, the state of Louisiana has put its enforcement strategy into practice in the form of nearly 4,000 lawsuits against its own residents, alleging breach of contract and seeking to take back more than $300 million in grant payments.

On its face, those numbers suggest the Road Home was a major success. It paid 119,000 homeowners a total of $9 billion in grants for rebuilding, and 96 percent of them fully complied. But a closer look at the lawsuits – a review another reporter and I did over the last few months, in partnership with the national investigative news organization ProPublica and The Times-Picayune – lays bare a key flaw.

The constant changes in Road Home rules -- intended to help struggling homeowners, but likened by one state policymaker to building a ship that’s already underway -- left many of the most vulnerable grant recipients trapped.

At least three-quarters of the people being sued -- more than 3,000 families according to a database of lawsuits provided by the state -- are not accused of failing the main Road Home requirement of rebuilding and reoccupying their storm-damaged properties. Rather, the state is suing them and seeking to recover about $100 million in grant money from them only because they failed to lift their homes higher off the ground or perform other improvements to make their houses more resilient against future storms.

The fine print in the grant agreements homeowners signed gave them three years to elevate their homes a foot above the base flood elevation in their area. But homeowners and former Road Home officials who worked for the state’s contractor, ICF Emergency Management Services, say that program representatives told homeowners they could use the elevation grants on repairs.

The state is now suing ICF for mismanaging the Road Home, but an ICF spokesperson says it “worked within the policies put in place by the state.” The lawsuit, filed in 2016, is still pending.

The extra $30,000 grants the Road Home paid for elevation went to approximately 32,000 homeowners. State records show that would have covered only about a third of the average cost of lifting a slab-on-grade house above the base flood elevation. That left many of those recipients of Road Home elevation grants with a requirement to elevate that they couldn’t afford.

The state even acknowledged as much by creating a separate federally funded grant program for anyone who got the Road Home elevation grants, but that didn’t get going until 2011 and only had enough money to cover about a third of those eligible.

The state tried again to help them in 2013, when it announced that elevation grants could be reclassified as compensation for the overall damage to a home and used for repairs instead. But that required the homeowners to produce receipts or canceled checks from work done seven or eight years earlier, something many couldn’t do.

“These are good, hardworking people just trying to do the right thing,” said Jay Hebert, an attorney at Southeast Louisiana Legal Services, who represents dozens of low-income defendants in the lawsuits. “They did what they were supposed to do, which is rebuild their home so they could put it back in commerce and live in it.”

Chapter 2 "Where do we go from here?"

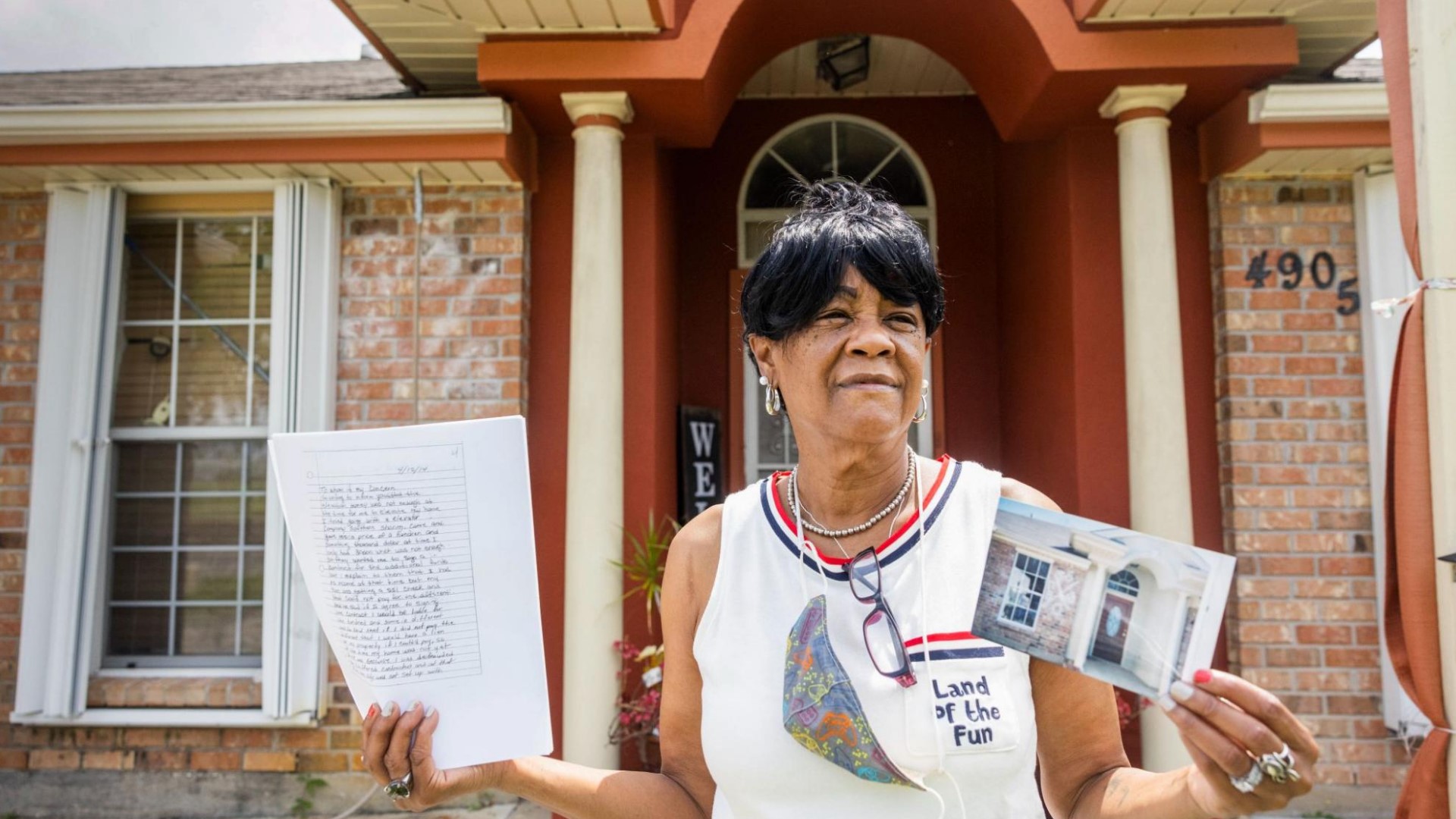

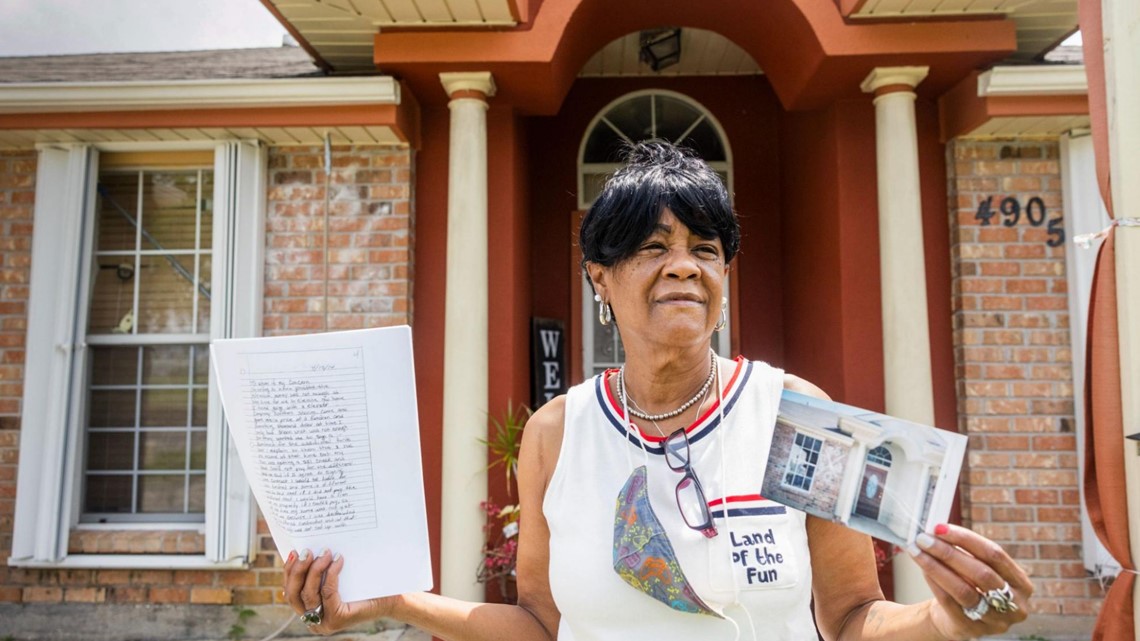

One homeowner who says her Road Home experience has been another disaster is Cherylyn Davis.

She used insurance proceeds from the murder of her son to build a new house in New Orleans East in April 2005, only to see it destroyed by Katrina four months later. Davis said unscrupulous contractors made off with $20,000 of her Road Home grant, a problem many homeowners encountered after Katrina.

“I had just lost my son. I just lost my house. And so, I mean, different people coming to you, to your door, giving me cards and stuff,” she said. “So, I took a card and took a chance and the guy ran out with my money.”

She thought it was good news in 2009 when the Road Home supplemented her rebuilding grant with the $30,000 elevation grant, but it turned out to be fool’s gold.

“One (elevation contractor) told me it was going to cost 100-and-something-thousand,” she said. “And so, I was like, ‘Hey, 100-and-something thousand?' I say, 'All they give me is $30,000.’”

When the state sent her a letter in 2014 asking why she hadn’t elevated her house, she explained that she used the money on repairs, but had lost her receipts to prove it. She said she only made $720 a month and couldn’t afford to elevate, and she asked "where do we go from here?”

The state’s response in 2020 was to sue her. She said she didn’t know she had been sued until I told her, although Orleans Parish Sheriff’s records indicate she was personally served with the lawsuit. The state is seeking a default judgment against her.

Ironically, much of this could have been avoided if a much-maligned part of the Road Home’s original design hadn’t been changed to speed up payouts.

Chapter 3 Lessons Learned

Louisiana’s governor during and after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, the late Kathleen Blanco, set up the Road Home to disburse rebuilding grants in installments, as repairs were completed, the way most construction loans work.

Blanco argued it would ensure homeowners did the work while appeasing members of Congress who were reticent to give billions in federal aid to Louisiana because of its reputation for graft. But that method triggered environmental reviews on each property, which slowed the process to a crawl in 2006 and early 2007. In March 2007, the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development told Blanco the grants would have to be paid in a lump sum.

“It was the defining moment to erode the actual intention” of the Road Home, Blanco later told me in a 2013 interview.

And HUD seems to recognize that now. Paying for repairs as they are completed is now the only way the federal agency lets states disburse these kinds of disaster grants.

Louisiana's current recovery chief, Pat Forbes, says it's a key lesson-learned from the Road Home.

“It dramatically reduces the opportunity for this noncompliance at the end, where you give people money and ask them to go do a thing,” Forbes said. “We actually go do the thing and track the progress the whole time.”

Forbes says installment payments are slower, but they helped 17,000 Louisiana homeowners rebuild from the Great Flood of 2016, without anyone having to repay anything for failing to rebuild.

Davis wonders why she didn't get that same chance. She thinks it could have helped her avoid the pitfalls of rebuilding on her own.

“What are we supposed to do?” she asked. “Where are we supposed to go after we done went to the people that were supposed to help us?”

► Get breaking news from your neighborhood delivered directly to you by downloading the new FREE WWL-TV News app now in the IOS App Store or Google Play.