NEW ORLEANS -- As the world watches President Trump’s fixer, Michael Cohen, turn on him in real time, New Orleans’ most infamous fixer is emerging from the shadows to tell the behind-the-scenes story of how he flipped on his old boss, former New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin.

Nagin’s former Chief Technology Officer, Greg Meffert, releases his self-published book “Landfall” on Wednesday, the 13th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina.

Meffert served 30 months in a federal prison camp. Nagin is in the middle of a 10-year prison sentence, mostly due to Meffert’s withering testimony against him in 2014.

The New Orleans Advocate’s investigative editor, Gordon Russell, led The Times-Picayune’s investigation of Meffert, exposing his self-dealing technology contracts at City Hall starting in 2006. I later teamed up with Russell to expose how Nagin shared in the spoils of side businesses Meffert set up using city contracts and resources.

So, when it came time to come clean in his memoir, Meffert agreed to interviews with The Advocate and WWL-TV. He spoke with us last week, one day after Cohen pleaded guilty to financial crimes and swore under oath that Trump directed him to make hush-money payoffs to influence the 2016 election.

It’s been nine years since Meffert flipped on Nagin and four years since he admitted it under oath on the witness stand. But “Landfall” goes further in some respects, making it abundantly clear that Meffert and Nagin were “in cahoots” setting up side businesses long before Hurricane Katrina, and were silent partners in NetMethods, a side business that was – on paper, at least – owned by Meffert’s tech buddies.

Meffert said he and Nagin were unlikely friends, but were truly close, at least until Meffert was no longer useful to the mayor.

“Ray and I went from being total strangers to being super close so quickly. And it was mainly because of where we came from: We both came from these high-paying jobs that were rare in New Orleans and we had this sense of entitlement to us,” Meffert said.

Nagin was an executive at Cox Communications before coming out of nowhere in 2002 to be elected mayor. Meffert was the CEO of several technology firms, and Nagin hired him to use IT and data to reform City Hall.

But Meffert writes that they encountered an impenetrable wall of unwilling city workers, people Nagin referred to as do-nothing “We Be’s,” Meffert says, “as in, ‘We be here before you got here, we be here after you gone.’” Meffert, who makes self-deprecating comments about often being the lone white man in Nagin’s inner circle, acknowledges the “We Be” moniker is “politically incorrect,” but pins it on Nagin.

Meffert says he and the mayor set up the company NetMethods to work around entrenched City Hall bureaucracy. But instead, it soon became their main vehicle to make money: Meffert’s tech buddies would devise new IT systems for New Orleans under other company names, then would sell those systems to other government agencies through NetMethods.

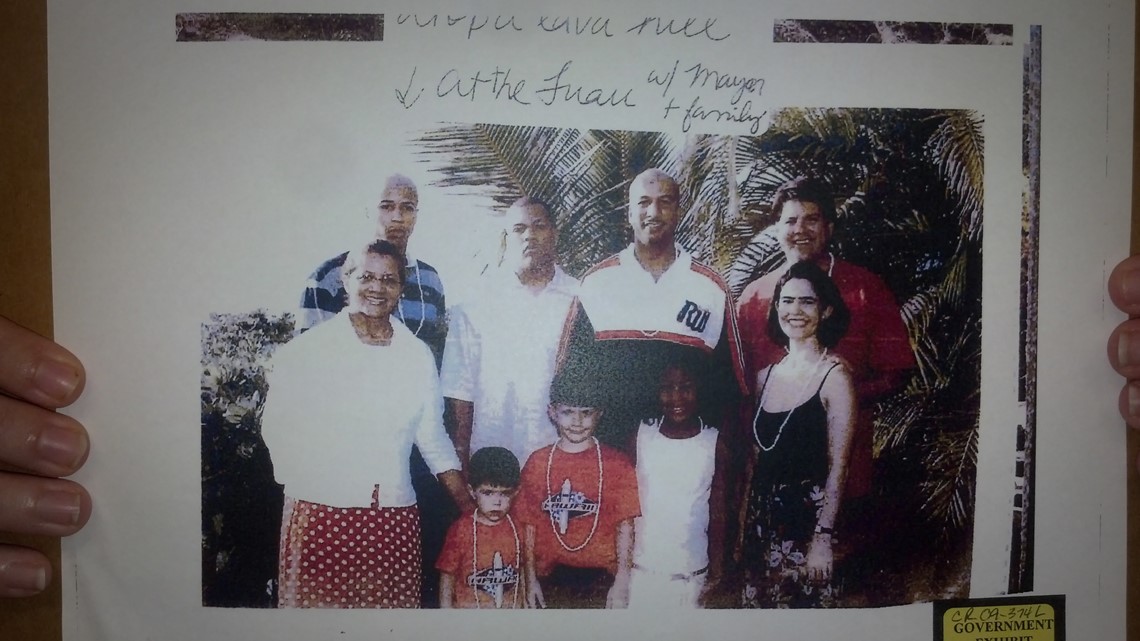

(Story continues under photo)

The lead tech buddy, Mark St. Pierre, provided Meffert with a NetMethods credit card, which Nagin also used for free vacations to Hawaii, Jamaica and elsewhere. Meffert pleaded guilty to taking $860,000 in bribes and kickbacks. St. Pierre was also convicted, with Meffert the star witness for the government against him, and went to prison.

Meffert lays out that path to corruption with powerfully introspective passages in the book, like this:

“I had been the idealist trying to disrupt a broken system but now I was that broken system, tilting the game in favor of those willing to pay to get a city deal. I had looked at myself as swimming through toxic City Hall waters but came to recognize that I had become a toxin myself.”

(Story continues under photo)

Meffert told WWL-TV he realized he had “crossed the line too late, obviously much too late.” It wasn’t the credit card and free trips that did it. It was shortly after he helped Nagin get reelected in 2006 and Meffert told the mayor he was burned out.

Nagin offered to make Meffert his Hurricane Recovery Czar. Meffert said that’s when it really dawned on him how corrupt they had become.

“And I can remember it feeling just like I had become part of that which I had been railing against,” he said in the interview. “And the fact that I couldn’t tell the difference anymore scared the hell out of me.”

Asked if it was difficult to admit that so openly in the book, Meffert said: “It was, but not probably for the reasons people would think. … You know, the people that loved and cared about me didn’t want me to flagellate myself like that, but at the end of the day it was more of a cautionary tale and I didn’t want to write a book that wasn’t completely and brutally honest.”

Meffert said his mother, Marcy, a former newspaper columnist and mayor of Leon Valley, Texas, who died earlier this month, inspired him to write the book. As did his wife, Linda, who stuck by him after almost taking the fall with him. She was charged with her husband for receiving some of the payments from St. Pierre, but was able to get the charges dropped by completing a pretrial diversion program in 2011.

The influence of those two women may explain why Meffert avoided writing about some of the more salacious details that he already testified about during the St. Pierre and Nagin trials. No mention of using NetMethods to hire strippers for wild sex parties on a yacht. No mention of the crime camera deals that exposed much of the fraud scheme, but infamously only helped New Orleans police catch one criminal.

“There was so much paint on that barn I just didn’t see the point of putting one more coat,” said Meffert, who falls on the sword plenty in the book, but also complains about the wall-to-wall news coverage and the aggressiveness of the FBI and federal prosecutors.

But he didn’t shy away at all from what he repeatedly called his “bromance” with Ray Nagin. In one passage, he claims that future mayor Mitch Landrieu tried to poach him from Nagin’s campaign heading into the May 2006 runoff between the two candidates. Meffert says Landrieu tried to get him to “switch jerseys” but he said no.

(Story continues under photo)

“My bromance with Ray had already reached levels that made the decision easy, even as I thought we were going to lose,” Meffert writes. “I thanked Mitch but declined. In retrospect, I look at that moment now and realize how clear an opportunity that was for me to get off my toboggan ride toward the gallows. At that point, though, I was still in love.”

Asked about his “love” for Nagin and if he misses him now, Meffert said, “Oh no. I don’t miss him. It doesn’t change the way I felt about him, that’s why I wrote about it in the book. I really cared about him.”

That kind of fawning language is reminiscent of Cohen, who once said he’d take a bullet for Trump.

Meffert tried to take a metaphorical bullet for Nagin in the summer 2009 when he said he was totally caught off-guard by an FBI visit to his house on Park Island, just a couple doors down from the Nagins’ home.

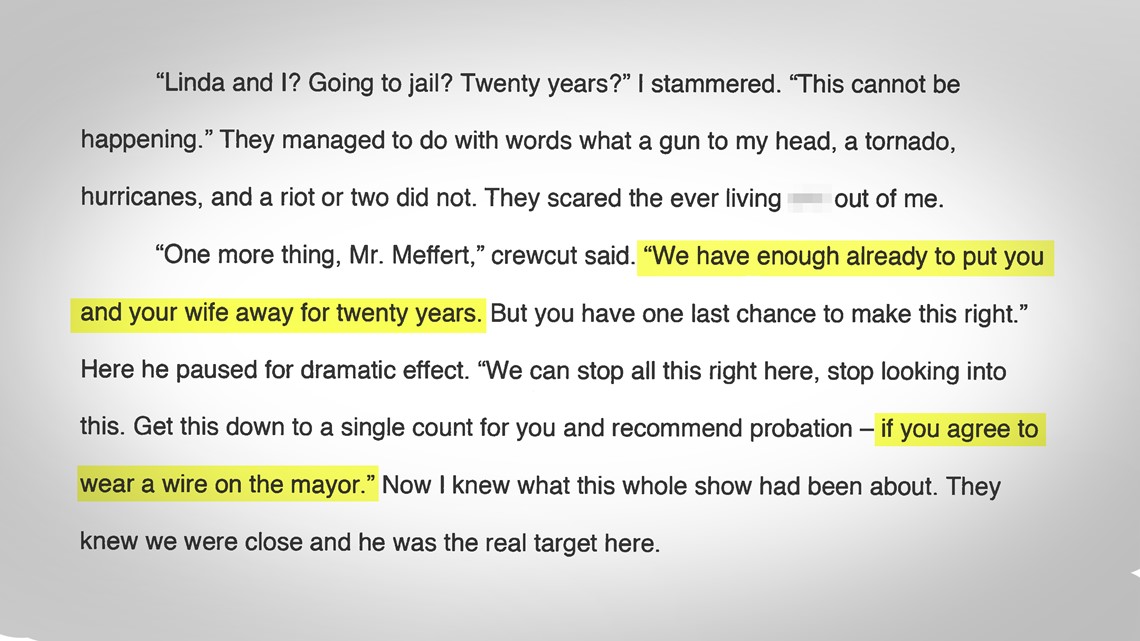

Meffert writes that an FBI agent he calls “crewcut” told him he could spare himself and his wife major prison time if he would wear a wire on the mayor. Meffert not only rejected the offer, he immediately ran down the street to Nagin’s house to warn him, he writes.

(Story continues under photo)

He claims in the book that Nagin betrayed him within 48 hours and gave secret grand jury testimony against him.

Nagin has declined interview requests from both WWL-TV and The Advocate, but some of Meffert’s claims are contradicted by other witnesses and the historical record. First, Meffert testified in the St. Pierre trial that the FBI first made it clear he was a target of their investigation in a February 2009 visit to his house, not in the summer of 2009.

Asked about that discrepancy, Meffert said he was, indeed, referring to the February 2009 meeting in the book. But he said he also had a series of other meetings with FBI agents that stretched into the summer.

More significantly, multiple sources with knowledge of the investigation have said Nagin was not in the government’s crosshairs yet when the FBI first went after Meffert. The FBI has publicly stated that Nagin didn’t become a target of the probe until the summer of 2009, when they received an unsolicited tip from a mortgage fraudster in New Jersey who said he made a $50,000 bribe to Nagin’s granite countertop business.

What’s more, it’s not clear if Nagin ever testified before a grand jury, and his statements in depositions and in public for years afterwards indicated unwavering support for Meffert and his innocence. Meffert acknowledges he flipped on Nagin long before Nagin was even charged with a crime, but writes that testifying against his old boss was made easier when he learned later that Nagin “betrayed” him.

(Story continues under video. Can't see video? Click here)

“I didn’t find out for years later,” Meffert said in the WWL-TV interview. “It was people talking about grand jury documents. I saw and emails he sent and things like that that were not protected necessarily, that were him basically saying it was all my wild idea.”

Beyond the corruption, Meffert tells a lot of behind-the-scenes stories from Katrina and the long recovery process – including juicy anecdotes about political figures like George W. Bush, Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton and national media stars like Anderson Cooper, Geraldo Rivera and Ted Koppel.

Meffert took issue with my use of the phrase “snakes on a plane” in a Times-Picayune article about the January 2007 private jet Meffert arranged through crooked contractor Aaron Bennett. The flight carried Nagin to the New Orleans Saints’ first NFC Championship Game against the Chicago Bears, then on to Las Vegas to connect with one of the criminals who bribed him, Frank Fradella.

But Meffert also professes in the book to have been taken aback by brazen in-flight bribery efforts by Bennett, who provided the plane, the football tickets and introduced Nagin to Fradella, then got a no-bid deal with City Hall as soon as they returned to New Orleans.

Bennett “mentioned the major construction company he represented looking to ‘partner up’ with both the city and Ray ‘personally.’ Subtlety was not this contractor’s strength,” Meffert writes. “Nakedly he laid out the quid pro quo: If the mayor hooked him up with city business, he was happy to give side work to ‘whoever you want.’ Even I felt wildly uncomfortable listening to the pitch made this bluntly.”

Bennett was named but never indicted for bribing Nagin and ended up being convicted on unrelated corruption charges, for which he violated his parole. He avoided having to testify in the Nagin trial, and yet was lauded by federal prosecutors for his “cooperation” in the case, which helped him get a sentence that was less than half of Meffert’s 30 months.

Asked if he resented that, Meffert said, “What I went through, I wouldn’t wish on anybody.”

Meffert said he hopes the book brings him at least some redemption, by reminding readers how he worked closely with Nagin and first responders in those dark days before and after the levees broke, fought to streamline the city’s multiple assessors and modernized City Hall’s computer system.

“I guess, all I was trying to accomplish -- after all these years of forced silence and all the stories that were written – (was) just to make the book a love letter to the city I miss,” he said.

David Hammer can be reached at dhammer@wwltv.com.