NEW ORLEANS -- Until the Deepwater Horizon exploded in 2010, killing 11 men and setting off a three-month oil gusher, most of us never heard of a blowout preventer.

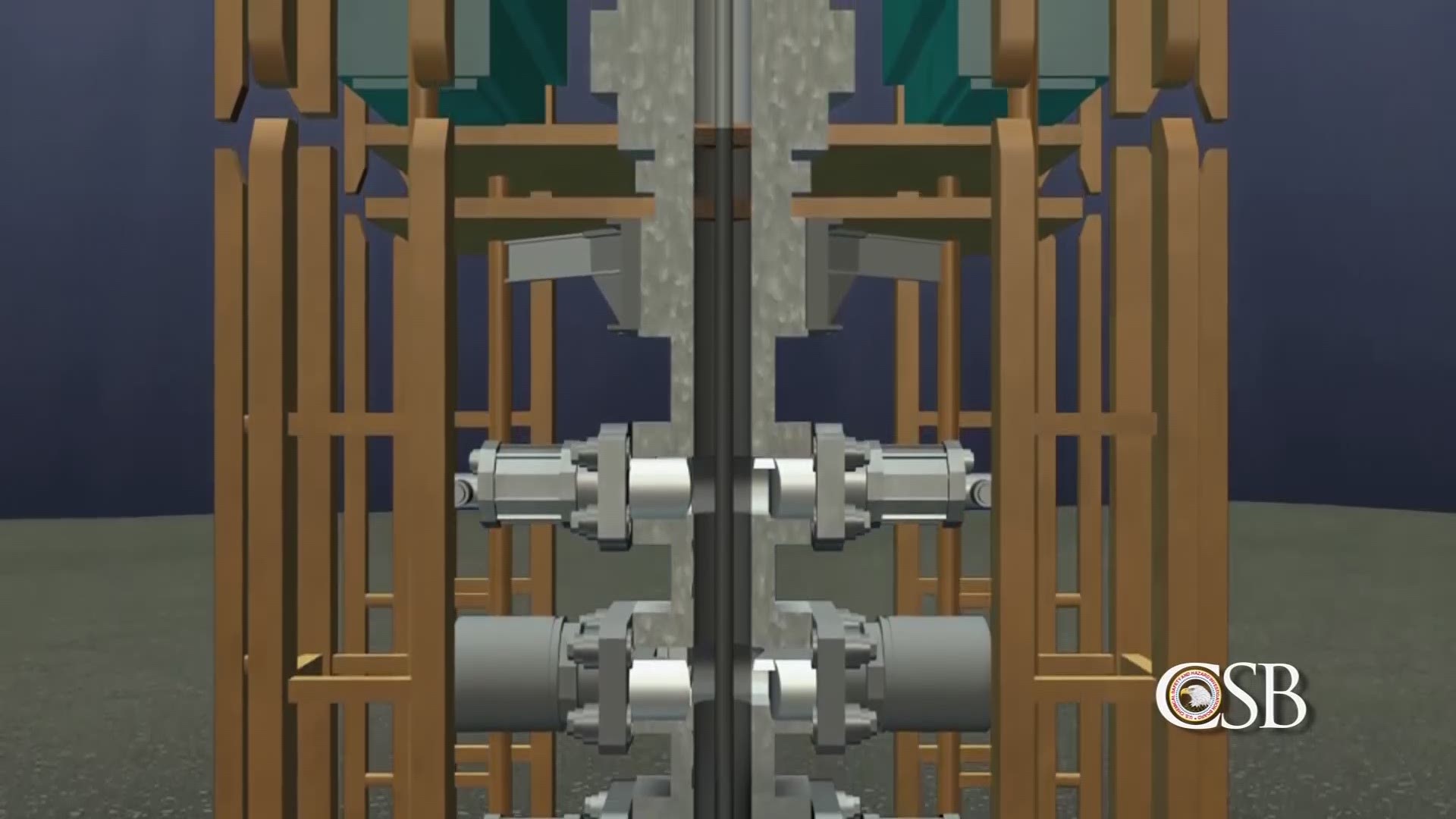

Now, this 400-ton, four-stories tall contraption of steel and tubing is at the center of a dispute over how to make offshore drilling safer. The BOP's stack of valves and pistons and rams are designed to shut in a deep sea well in case it starts spewing oil and gas. But several investigative reports showed that the Deepwater Horizon's BOP failed miserably at BP's Macondo well, and a handful of others have not been able to contain out-of-control wells since then.

![Blowout preventer rules still short on power [video : 77791748]](http://wwl-download.edgesuite.net/video/1420743/1420743_Still.jpg)

And yet, more than five years later, the government is only just now trying to address some of those problems with a new offshore drilling safety rule proposed by President Obama's Interior Department in April. Congress, which has failed to take any meaningful action on offshore safety since the BP spill, held a contentious hearing about the proposed new rules on Dec. 1.

“The idea that we're sitting here now, almost six years after those hearings that you mentioned, still talking about putting in rules to strengthen the last line of defense, that fail-safe in offshore drilling, is incredibly disturbing,” said Jackie Savitz of Oceana.

The oil and gas industry isn't taking kindly to the government's proposed BOP rules, which would require certain redundant equipment, hydraulic upgrades and inspections every five years. Environmentalists say the rules are overdue, but fall short of ensuring safe operations.

It's all become very political, with Republicans like Sen. Bill Cassidy of Louisiana complaining that they will force rigs to stop drilling for months on end.

“How do we achieve safety, but not kill an industry with a thousand cuts?” he asked at the Dec. 1 hearing.

Democrats like Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts took the opportunity to call out the American Petroleum Institute's Erik Milito.

“You said, 10 days before the explosion, that new technologies – quote – ‘close and shut off any type of opportunity for any type of liquid or fluids to get into the environment,’” Warren said to Milito.

“That was the intent,” Milito said.

Warren: “The intent, but I take it that was not the fact.”

Milito: “That was not…”

Then Warren, who argued the American people could not trust the industry to be honest about how safely it operates, cut him off: “No, that was not in fact.”

The fact of the matter is, the industry has made a lot of safety improvements since the BP disaster of its own accord, but the biggest challenge remains the BOP and especially its so-called "fail-safe" component called blind shear rams.

BOPs keep getting larger as the industry drills deeper wells under higher pressures, but the blind shear rams still don't have enough power to cut through some of the thicker tools and pipe connectors that are constantly passing through a BOP while a crew is drilling. The biggest, 15,000 psi BOP models can deliver about 2 million pounds of force to close the slicing rams, but they may need twice that much power to actually cut all of the heavy tools and equipment that could be in their path when it's time to seal against a blowout.

“We've got a last line of defense that doesn't work if certain type of pipe is in there. Doesn't work 10 percent of the time. Doesn't work if the pipe's not aligned right. Doesn't work if you wait too long to press it. We need something that works,” safety consultant Ken Wells said.

Wells represents a company in Houston called BOP Technologies. They are proposing a possible solution that so far has been overlooked by both industry and government. Jay Read is the company's idea man. He used to work at Cameron International, the company that built the Deepwater Horizon's BOP.

“This technology will save lives and environment and property,” Read said. “It's got what the industry needs.”

Read and his partners at BOP Technologies say they have developed a smaller system designed to make the blind shear rams more powerful, giving them a better chance to cut through any pipe or tools, and seal the well. Instead of adding more girth, Read's idea uses intensified hydraulic fluid, taking advantage of the larger surface area below the blind shear rams to multiply the force provided by the hydraulics. He says 5 million pounds of force can be delivered this way to the space behind the pistons of the blind shear rams, pushing them together with enough power to cut anything in the well bore.

Wells thinks it might take tougher rules to force the industry to accept such a change to a blowout preventer design that's basically stayed the same -- except for the size -- for 80 years.

“And if the government can just see that there's a solution out there, I think they're going to want it to cut everything in the well bore,” Wells said. “At this point they're being reasonably prudent because industry's going, 'With what we have today, we can't guarantee that.'”

Unfortunately, without that guarantee in a new offshore drilling safety rule, many fear yet another deepwater disaster.