NEW ORLEANS — When Homer Plessy, commissioned by the Citizens Committee, refused to move from a white's only railway car to the blacks-only car, he was arrested and convicted of violating the Louisiana separate car act of 1890.

In court, Plessy's lawyers argued the state had violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment, but presiding judge John Ferguson ruled that Louisiana could enforce that law without violating the Consitution.

The case would make its way to the U.S. Supreme Court, and the landmark 1896 decision in the Plessy v. Ferguson case had implications that would last generations.

Americans were separated then by a doctrine that came to be known as separate but equal. Decades later, the same decision brought two of the most unlikely people together, leading them on a journey of reconciliation.

Keith Plessy said he always knew he was related to Homer Plessy.

"I was able to learn about my ancestors for the first time when I was very young, but I was not very interested in finding out about it," Keith said.

Keith said he was stunned to learn that his great-grandfather, Joseph Gustave Plessy was Homer Plessy's first cousin.

In 1892, Homer Plessy, a black man, famously defied the Separate Car Act in an act of protest.

"I didn't know I was that close to the man," Keith said. "I didn't know I was related to him in that way."

Keith started to dig more into his past, learning bits and pieces beyond what America knew about his distant relative.

Most of that done with the help of Keith Weldon Medley, the author of 'We as Freeman'

"He actually introduced me to a cousin who was 200 years removed from the first two Plessy's that came to the United States," Keith said.

Meanwhile, a photographer, Phoebe Ferguson, got a phone call from a man who bought the home of Judge John Howard Ferguson, who presided over the Plessy v State of Louisiana case.

The man had bought the judge's house on Henry Clay Avenue, and he was looking for pictures.

"He wanted to find a family member who might have some photographs, so he could renovate it to it's exact," Phoebe said.

While the photographer couldn't find pictures of the house, she did find something else.

"I'm the judge's great, great-granddaughter," Phoebe said. "Yes, that was a bit of a shock."

With the help of Keith Medley, Phoebe was about to re-visit a crossroads in history and meet the man whose name appears on the most consequential legal cases in the country's history: Plessy v Ferguson.

"He said 'hi, I'm Keith Plessy,' and I said 'hi, I'm Phoebe Ferguson,'" Phoebe said. "Then, I just started apologizing for everything that ever happened from slavery to civil rights. It was just so difficult in a way to know this history has harmed so many people for so long,"

WWLTV's Charisse Gibson asked Phoebe why she apologized.

"I think it is the responsibility of all white citizens to understand their history, our history and the legacy that it has left on an entire population of African American citizens," Phoebe said.

"I just politely forgave her for everything because I told her it's no longer Plessy v. Ferguson; It's Plessy and Ferguson," Keith said.

The chance meeting between two people whose relatives were on opposite ends of history turned into an opportunity to confront their past as a way to move forward, together.

"We realized our union could bring people together around equity and race issues," Phoebe said. "We could use the history of the case to talk about those issues."

The Plessy and Ferguson Foundation was born.

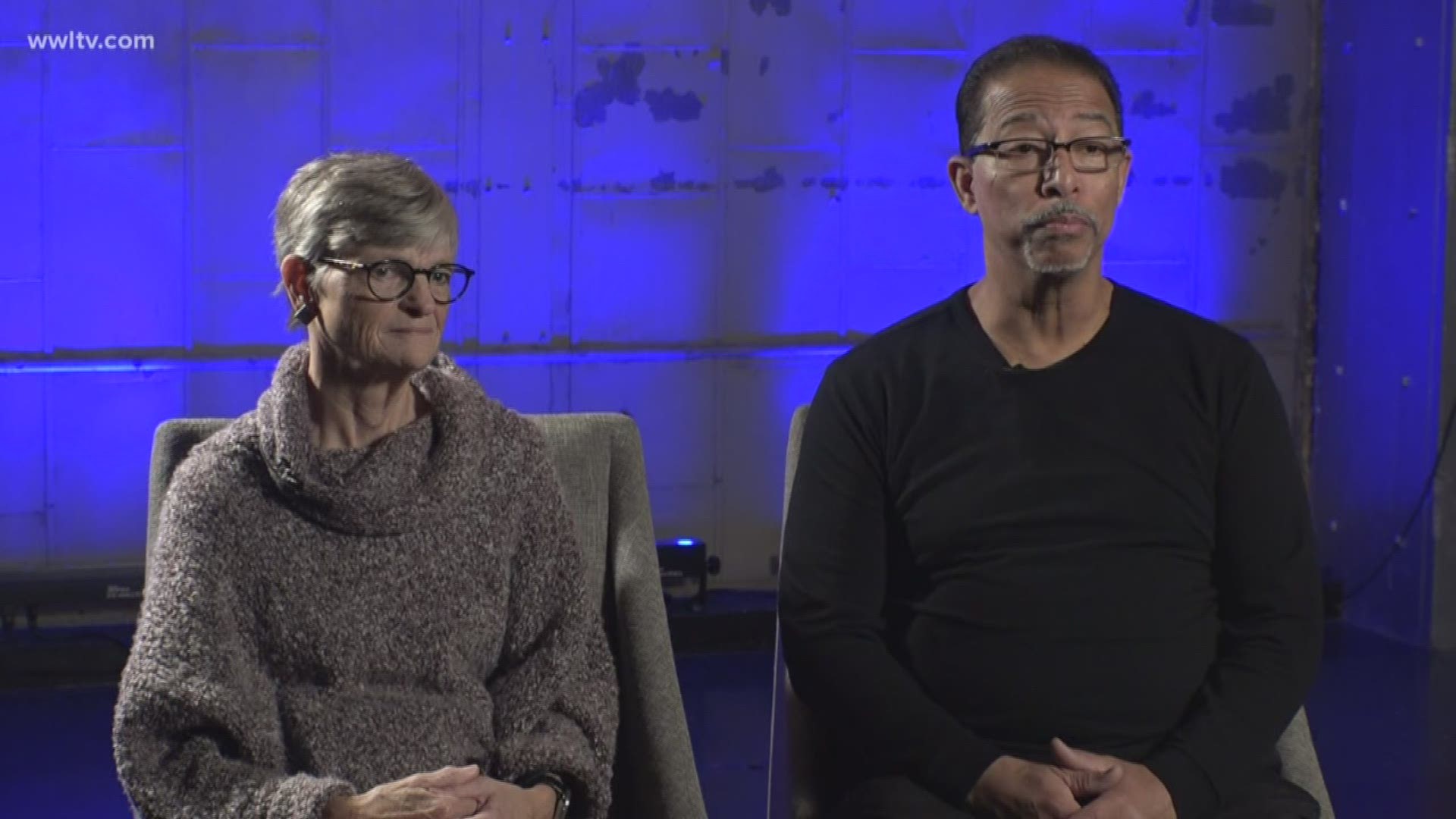

Keith Plessy and Phoebe Ferguson now travel the country, sharing their journey of reconciliation and preservation.

"Even though we experienced a natural reconciliation when we met, we are learning more about how to bring people together," Keith said.

Throughout New Orleans, their foundation works to highlight sites of African American achievement, and they do that by presenting historic markers.

The first, of course, being the Plessy v. Ferguson marker near the site where Homer Plessy was arrested for violating the separate car act, hoping those who read it understand the place their ancestors held in New Orleans history.

"We call ourselves partners in history," Phoebe said. "It's really about opening your heart, being willing to share dialogue and listen to others and then be willing to act on what you're hearing — and figure out how you can make a difference. Our coming together only matters if we can share that message. If we can share our shared history."

► Get breaking news from your neighborhood delivered directly to you by downloading the FREE WWL-TV News app now in the IOS App Store or Google Play.