BATON ROUGE, La. — About 90 days after Troy Barnes was released from Louisiana State Penitentiary, he returned — but this time, he wasn’t in handcuffs.

Instead, he was personally escorted by the warden, a gift in tow: beautiful, hand-carved shelves to be installed in one of the dormitories and filled with 500 carefully selected books. Barnes, who learned carpentry while in prison, built them himself.

“In prison, you really don’t have beautiful things to see,” Barnes said. “To be able to wake up and see a natural, beautiful thing that was built by someone who left and returned to bring it there — it would give the guys hope.”

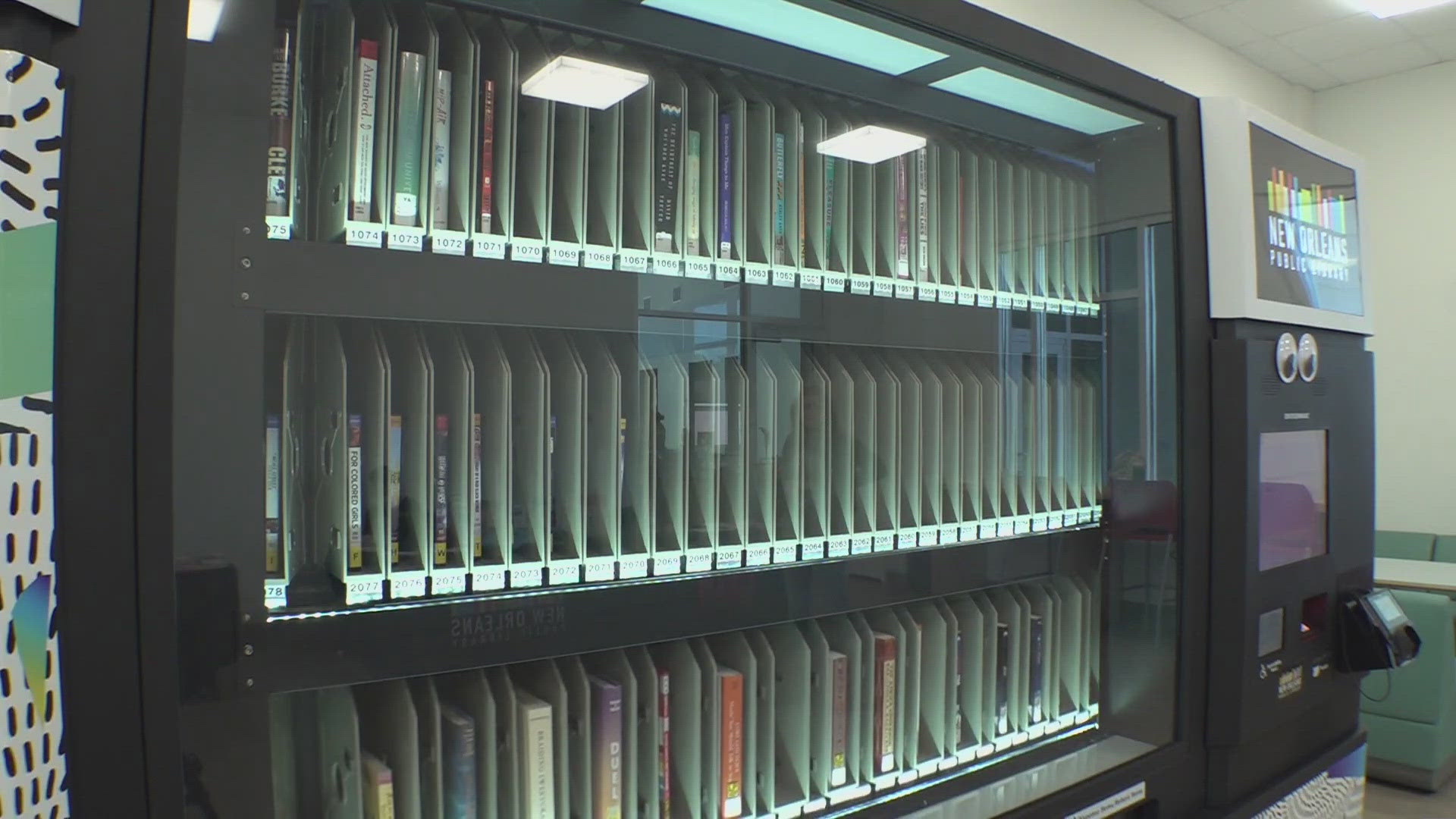

It was one of two “Freedom Libraries” erected at a Louisiana state-run prison this month. The other, a smaller version, is located at Elayn Hunt Correctional Center. Barnes built them both.

The libraries are part of Reginald Dwayne Betts’ vision to bring hundreds of books to prisons across America. Betts, a 2021 MacArthur Fellow, founded the nonprofit Freedom Reads to realize his dream of infusing prisons with literature and beauty in the hopes of changing the lives of those locked inside for the better.

MacArthur Fellowships are nationally prestigious grants that the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation gives each year to “extraordinarily talented and creative individuals” across the country.

“We have a chance to contribute to another chapter in the history of incarceration here in the South — one that is about mercy, hope, and creating opportunity for self-reinvention inside,” Betts said. “I know firsthand how literature empowers us to confront what prison does to the spirit.”

Before graduating from Yale Law School, Betts was sentenced to nine years in prison with the Virginia Department of Corrections after pleading guilty to a carjacking charge at the age of 16.

During his time in solitary confinement as a teenager, Betts yelled out to the other men incarcerated with him: “Somebody, send me a book!” One of them slid Dudley Randall’s “The Black Poets” under his cell door, sparking an interest in ideas that led him to become a poet, lawyer and prison rights advocate, according to the Freedom Reads website.

“We put millions of people in prison,” Betts said. “I wanted to see what it would mean to put millions of books in prison. It’s not just access to reading materials and building something beautiful. It’s being present, even for a moment, in the lives of people who are incarcerated.”

Officials with the Department of Corrections worked with Betts’ organization and chose the prisons where the libraries would be housed.

“I had the opportunity to see Dwayne at a conference not too long ago, and I was so impressed with his presentation and the work he is doing with Freedom Reads,” said Corrections Secretary Jimmy LeBlanc. “This donation means so much to our prisoners as it will help broaden their horizons through reading.”

Unlike prison libraries, which are not available to inmates around the clock, the portable Freedom Libraries are housed in the dorms, allowing 24-hour access to hundreds of books.

Barnes, who served two and a half years at Angola before his release, also pointed out that some inmates are disabled, requiring canes or wheelchairs. Placing the libraries in the dorm directly means “they don’t have to risk a far walk,” he said.

The literary selections were curated through consultations with “thousands of poets, novelists, philosophers, teachers, friends and voracious readers,” creating an “indispensable” collection of beloved books, according to a press release from the nonprofit.

“I was asking people what books were the most beneficial or beautiful for them to read,” Betts said.

The libraries include works by Shakespeare, Toni Morrison, William Faulkner and Ernest Gaines. Inmates can contribute their own books to the collection as well, ideally starting conversations where they share their favorites.

So far, the only other Freedom Libraries reside in Massachusetts, Betts said. Louisiana was meant to house the first installations in the country, but the coronavirus pandemic disrupted the schedule.

”(The library) gives them, I think, the possibility of having a different insight into how they exist in the world,” Betts said. “I think this becomes a reminder of what just might be possible.”

Like Betts, Barnes knew as he crafted the libraries that he wanted to bring something timeless and valuable into a space where many despair. Often, he got lost in the patterns and grooves of the wood while carefully choosing the most beautiful pieces for the men to admire.

Sometimes, he said, depending on how the tree grows, you can see oceans.