LAFAYETTE, La. — As schools in Acadiana and across the South began to integrate 50 years ago, families and communities were heading into new territory.

Parents prepared their children for a changing academic environment and prayed the changes would go smoothly; others moved their children altogether, opting out of this new landscape.

Some children struggled with uncertainty and fear, while others seemed to easily accept the change.

Whatever their experience, integration impacted an entire generation, leaving a lasting impression on communities and the people in them.

‘DON’T HATE; JUST KEEP YOUR HEAD HELD HIGH’

Antoinette Chaffers’ Pete, 65, grew up in west Crowley and attended a small, all-Black Catholic school connected to her church and run by the Sisters of the Holy Ghost from San Antonio. St. Theresa Catholic Church still stands on West Third Street, but the school has long been shuttered and the sisters returned to Texas.

The youngest of eight, Pete jokes that the sisters gave her mother, a devout Catholic, a discount on tuition at the school that went up to eighth grade. Her siblings continued into Ross High School, the school afforded to Black students in Crowley during segregation.

But Pete would veer off her siblings’ path, starting ninth grade in 1971 as schools in Acadia Parish were integrated. She would be the first in her family to attend and later graduate from Crowley High.

It would be a big change for everyone.

“I was leaving a small, little Catholic school,” Pete said. “In the eighth-grade class, I was one of 10 – eight girls and two boys. Then I was about to make the biggest move into integration and into the high school in Crowley.”

She went through many emotions as the first day of school approached.

“I don’t want to say it was frightening – just mind-boggling,′ Pete said. “It wasn’t easy. We were always the minority.”

Pete said she lived through racism. “We were brought up in it,” she said. Racism was a shared experience for her community.

“We have to go through what life puts in front of us,” she said. “We had a faith that carried us through anything.”

So she relied on her faith and her family for strength.

“I remember my grandma — she was a hardworking little lady — she could see I was really, really nervous about my first day,” Pete recalled. “She said, ‘You have to work hard because white people are really smart. Show them what you’re really made of. Don’t hate; just keep your head held high.’”

She did just that and more, joining the pep squad and choir on top of giving her all in the classroom.

“I needed to be involved,” Pete said. “We needed to show Crowley High School we were just as good at everything as they were. In the classroom, I tried to do everything I possibly could.”

There were divided opinions about integrating schools at the time, even within the Black community.

“Some people were saying, ‘Integration is good,’ and some would say, ‘No, leave us where we are,‘” Pete said. “I wanted to be able to do what others do and get what others get. At St. Theresa’s we only got hand-me-down books.”

She said she felt support from her teachers and administrators during the transition.

“It was a challenge for these teachers as well,” Pete said. “They knew we were so, so apprehensive and nervous. They exhibited a compassion that would make us want to learn.”

That compassion would go on to inspire her to become an educator herself and later return as a teacher, administrator and now district leader in the school system she helped integrate.

“It was their kind of motivation, compassion, and love for learning that got me to want to go into teaching,” Pete said.

‘HERE WE GO AGAIN’

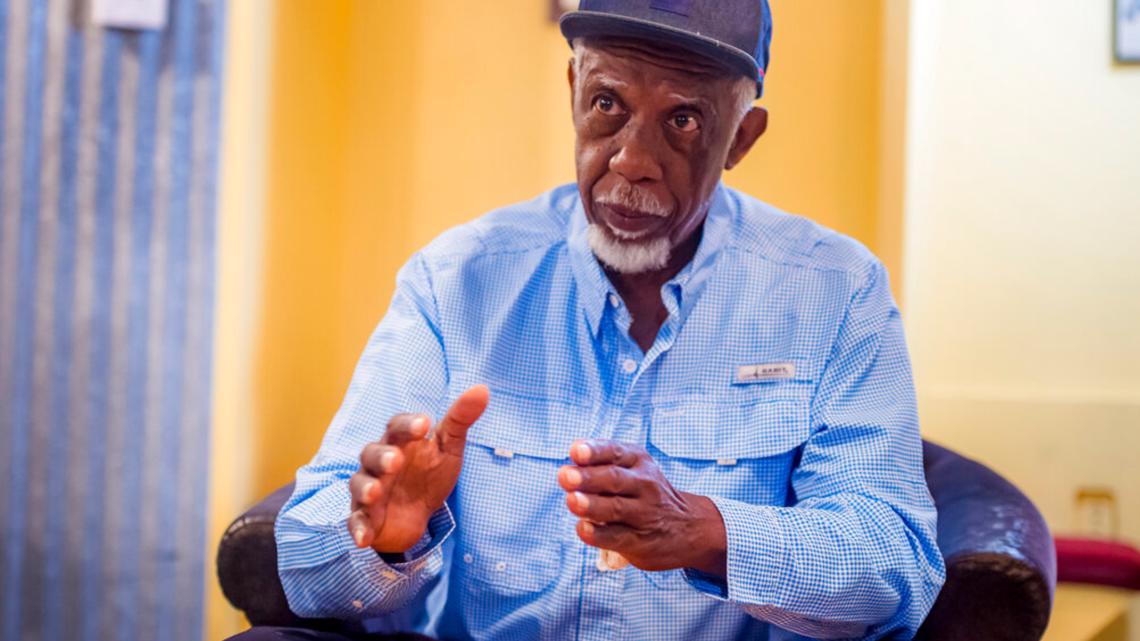

Greg Davis, 65, started 10th grade at Northside High School in 1971, but it was not his first experience with integration.

He’d attended segregated schools in Bogalusa until fourth grade when his mother moved him and his brother to a Catholic school in New Orleans that was integrating. The two boys would be among about eight Black students at the K-12 school, and the staff was not integrated.

“That was the worst thing she could have done,” Davis said. “It was a terrible experience. Most of the white people there didn’t want us there.”

His first two years there were filled with fights, as he responded physically to racial slurs and mistreatment from his classmates.

Greg Davis was the 2019 marshal of the Martin Luther King Jr. Day Parade. Davis, 65, started 10th grade at Northside High School in 1971. A major problem at Northside was that the student body was integrating but not the staff, Davis said.

“I stayed in the principal’s office,” he said.

After another year his family moved to Lafayette and he found something he said he didn’t know existed — a Black Catholic church — and it happened to have a school. He joined Immaculate Heart of Mary Catholic Church, attending its school and later Holy Rosary Institute, another Catholic school for Lafayette’s Black children.

“I thought I was in hog heaven because I wasn’t experiencing racism anymore,” Davis said.

But he would switch schools again after his parents divorced and couldn’t afford two kids in private school. His brother was older and closer to graduation, so they opted to let him finish at Holy Rosary while Davis attended the previously all-white Northside High as a freshman in 1970.

He said the first year “wasn’t so bad,” as there were only a handful of Black students at the school that was starting to integrate. The parish’s Black high school, Paul Breaux High School, remained open until the end of the school year, and the 950 students were sent to Northside and other public schools across Lafayette in 1971.

“When they closed Paul Breaux, which brought an onslaught of Black students (to Northside), it got really bad,” Davis said. “I thought, ‘Here we go again.‘”

Like the New Orleans Catholic school he’d attended, a major problem at Northside was that the student body was integrating but not the staff, Davis said.

“There were no Black teachers, coaches or administrators,” Davis said. “They didn’t want us there.”

So he and other students led sit-ins at the school, and administrators called law enforcement to campus, telling them to leave or be forced to leave, Davis said. The students elected Davis, a sophomore, as spokesperson to present their demands to the sheriff, school administration and superintendent.

He told them they wanted a Black administrator, a Black head coach of either basketball or football and Black people on the cafeteria and custodial staff. The men told him they would consider the demands and escorted Davis back to the gym, and the students left.

But the school system did not implement the students’ demands, leading to days of community marches.

“After that, we did marches — big marches — from Heymann Park to Northside High School,” Davis said. “One day we got there and the campus was surrounded by troopers. Because we were marching they wouldn’t let us in.”

Three adults were arrested that day and students sent home, according to The Daily Advertiser archives. It had been the culmination of four days of marches, and it didn’t end there.

Davis said demonstrations and walkouts continued, and students picketed the school board. His father, who was teaching in Lafayette Parish, was told by district leaders he would lose his job unless he told his son to stop. He refused but was able to keep his job.

“It was an empty threat,” Davis said. “But they did tell him the best thing he could do is get me out of here. They said, ‘There is a target on his back.‘”

Facing this threat, Davis moved to Port Allen and lived with his mother. It turned out to be his third time attending a school that was beginning to integrate.

He continued the fight against mistreatment there, leading walkouts at that school and an economic boycott of businesses in the city. He was arrested and expelled, and the NAACP sued the school system to allow him and others to return.

“It was scary,” Davis said. “The economic boycott, that was scary. Quite a few white people were very angry. When we did the walkout and went to jail, that was scary.

“But we knew it was something we had to do to stop from being mistreated and to get Black teachers.”

He soon learned he was right, as he returned to Lafayette to escape yet another target on his back. When he started his senior year at Northside, he found the school changed.

“The school had a Black principal, Black teachers, Black head basketball coach,” he said, ticking off the demands he’d laid out as a sophomore. “It was a totally different atmosphere when I went back. ... My senior year was a great year.”

‘GOD HAS A PLAN’

Jimmy Meche, 86, grew up in what seemed to be the only white family in west Crowley at the time. The town was clearly segregated, and decades later west Crowley remains predominately Black.

“I didn’t know there were white kids other than on Sundays until I started school,” said Meche, who attended a white Catholic school and later entered the segregated public school system.

His mother, an Italian immigrant, ran a grocery store at the front of their house, and he remembers witnessing racism in action as an elementary student sitting on the steps of the store.

One Sunday morning he saw a friend of his, a Black boy a little older than him, beaten by a white police officer who had been driving by.

“A police officer stopped that car and beat that Black fella,” Meche said. “He bled him. I’d never seen that.”

He ran to get his mom, but by the time they returned it was over, and the officer was gone.

“I was hurt by what I would see,” he said. “It affected me.”

Years later, Meche believes experiences like this gave him a perspective and understanding that other white people in Crowley and across the South might not have had.

“I know why God had me in that situation,” Meche said. “He knew before I did I would be in the middle of (integration). God has a plan.”

Meche graduated from Crowley High School in 1952 and would return to his alma mater to teach civics and coach. But his first year in administration would be at another building.

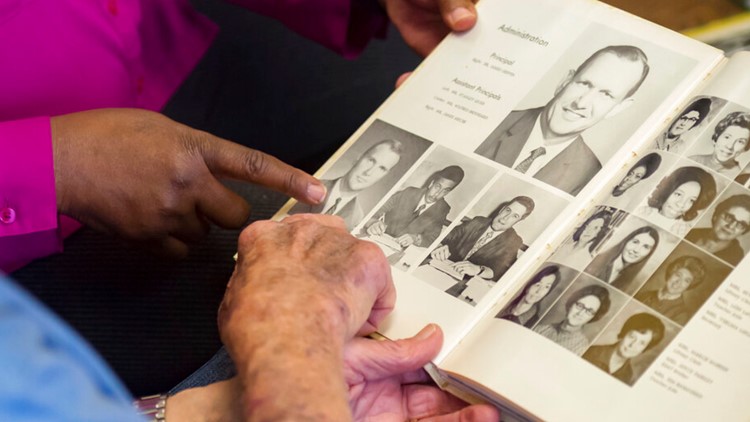

He was tapped to be an assistant principal in 1970-71 as the Acadia Parish School System combined the student bodies of Crowley High and Ross High School into one. Such large numbers would require more space, and the district began building a new, larger CHS on land to the north of town.

In the meantime, the new Crowley High student body was split by grade levels over two campuses. Some went to the Crowley High building that had housed only white staff and students for decades. The building still stands and serves as Crowley Middle School today.

Students in other grades went to school less than a mile away at what had been Ross High, which now is used for early childhood education as Ross Head Start. That’s where Meche spent most of his day.

“The state didn’t make anything easy on those Black kids,” Meche said. “They gave up their school. We (white people) didn’t give up anything except letting Black people come to school with us.”

Like other places across the South, it wasn’t simple or easy when Crowley schools “came together,” as both Meche and Pete called integration.

“It was tough on our community,” he said. “First day of school, everybody was scared. Parents were calling the police to check the school. You had friends that you knew who would call the police. It was like they wanted something to happen.”

Thankfully, though, nothing did. While it wasn’t perfect, Meche says, he didn’t see fights or dangerous incidents at his school.

Rather than outright fights, many opposed integration by pulling their students from the school, opting instead for private and still segregated schools. Many teachers left, too, including a lot of young Black teachers, Meche remembers.

“When you look at what I saw, they didn’t want their kids with Black kids and it was the same on the other side,” he said. “How do you keep it going? Both sides were scared.”

His answer was to be as visible as possible, for students and staff at the school as well as in the community. He saw then how growing up in west Crowley would help him lead through this time.

“These people trusted me, on both sides,” Meche said. “I didn’t have a kid in that school whose parents didn’t know me. They grew up with me.”

He and his wife, Geri, kept their five kids in public, integrated schools.

“We knew a lot who didn’t, even real good friends of ours,” he said. “White parents wanted me on ‘their side.’”

“People would call me (and say), ‘Are you going to leave your children with that element in that school?‘” Geri said.

But about 15 or 20 white women in the town refused to remove their kids from public schools, Meche said. He believes that made a difference in creating change within the community.

“It helped me to see people like these ladies,” he said. “That’s what they don’t have now. White people with money have left.”

‘UNTIL I LEFT EUNICE I NEVER HAD A CLASS WITH A WHITE STUDENT’

Albert Hayes Jr.’s experience with integration in Acadiana came when he began to teach at Eunice Junior High in 1976.

Hayes, 69, graduated in the last class of Charles Drew High School, the all-Black school in Eunice that closed during integration.

“Pre-integration, I very seldom had a textbook that did not have a long line of signatures (of previous owners),” Hayes said. “The practice at that time was to upgrade the white schools and hand over books.”

He is thankful to have had “some of the best teachers in the area” at Charles Drew High owing to the limited professional options available to Black adults then.

“The opportunity for Black people professionally prior to integration was not that great,” he said. “So we ended up with teachers who in today’s economy might have been chemists and mathematicians. Since opportunities were limited, we had the benefit of their instruction.”

He attended the school from first through 12th grade and moved to Pennsylvania to study political science at Lehigh University on a scholarship.

“Until I left Eunice, I never had a class with a white student,” he said. “At Lehigh University, I was one of maybe 30 Black students.”

That took some adjusting, he said, but it was “sort of liberating, too.”

“It gave me an unfair sense of importance, being the only Black person in a classroom and extreme minority on campus,” Hayes said. “There was some pressure. On one hand, they assume you speak for all Black people, and the other, iin such small numbers you don’t have a great influence on the total picture.”

So he observed integration in his hometown from afar, staying in Pennsylvania a few years until he changed his major. He shifted to education, which wasn’t offered at Lehigh, and returned home to study at LSU Eunice. He later transferred to LSU’s main campus and finished his degree in Baton Rouge.

“When integration occurred there was some conflict,” he said. But his sister, six years behind him, seemed to enjoy her experience in the schools.

Then he experienced integrated schools firsthand as a teacher and community member. It was an ongoing process.

“I think the city of Eunice embraced it fairly quickly — first in sports and really much later socially,” Hayes said. “An example: we won a state championship in football in the mid-’80s and we had our first integrated prom in 2000.”

Charles Drew High School closed after Hayes and his classmates graduated, but the building still stands on Martin Luther King Drive and houses Central Middle School, one of the schools Hayes now represents on the St. Landry Parish School Board.

The school and the experiences he had there have had a lasting impact on him, especially his teachers.

“I found myself emulating some of their characteristics, their nuances,” Hayes said. “Even today I feel like they have a lasting effect on me as a school board member.”