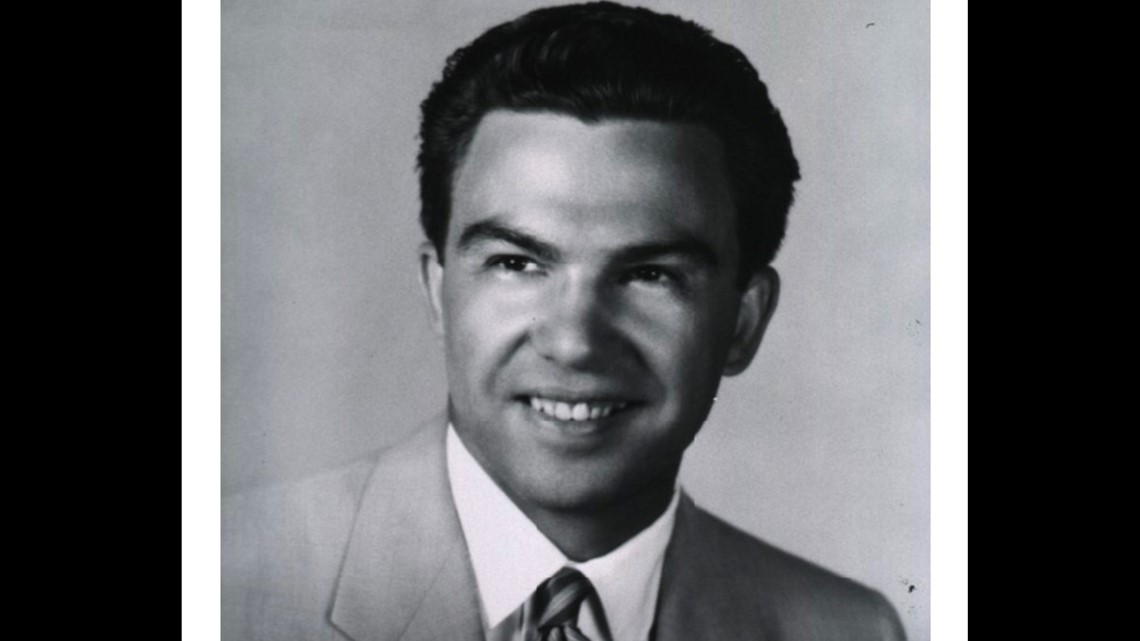

Dr. Irwin Marcus, a renowned New Orleans psychiatrist, psychoanalyst and author who spent more than 65 years in the treatment and study of mental illness and its effects on children and adults, died Sunday. He was 102.

His wife, former WWL-TV anchor Angela Hill, said Dr. Marcus – whose vitality amazed friends and colleagues half his age – was still counseling patients up until earlier this year.

She said he was perfectly suited for his profession, as a natural listener who genuinely cared for those he treated.

“He understood people so well and was such a good listener that people were comfortable confiding in him,” Hill said. “That – combined with his fascination with the brain, human behavior and the importance of relationships – gave him a tremendous ability to help people. He was born to do what he did.”

His son, Dr. Randall “Randy” Marcus, said he met many people over the years who credited his father with saving their life. He said he and his two sisters also benefitted from their father’s gifts as a listener and counselor.

“That’s what his kids, friends and patients loved so much about him. His advice was always so solid. I also think he was most proud of the fact that he was able to help thousands of New Orleanians over the years who were dealing with mental disorder or trauma find a way through it.”

Dr. Marcus was particularly respected for his role in establishing the child and adolescent psychiatry program at Tulane University School of Medicine. He moved to New Orleans from New York in 1951 after being recruited to establish the program, originally called the Family Study Unit. According to Dr. Charles Zeanah, a Tulane professor of psychiatry and pediatrics and the program’s current vice chair, it is the oldest program of its kind in the Gulf South.

Dr. Marcus was also a founder and former president of the New Orleans Psychoanalytic Institute, former chairman of the psychiatric department at Touro Infirmary and emeritus clinical professor at Louisiana State University Medical School.

Born in Chicago on March 18, 1919, Dr. Marcus put himself through college during the Great Depression, studying at the Illinois Institute of Technology and later the University of Illinois School of Medicine. His son Randy said Dr. Marcus' early interest was in neurosurgery, though he would later treat and study the brain rather than operate on it.

He performed his medical residency at Chicago’s famed Cook County Hospital, one of the largest and most well-known teaching hospitals in the country. There, his wife said he displayed the gift for listening which would form his professional career.

“He would go back to visit with patients after his shift had ended, just to check on them, ask how they were doing and learn more about them as people,” Hill said. “Other doctors questioned him for that, but to me it was so emblematic of the empathy and care he had for his patients, believing that being a doctor is about more than just treating someone’s medical condition.”

He was in his third year of medical school when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on Dec.7, 1941. The next day, he enlisted in the U.S. Army. Rising to the rank of captain, he served the Army Medical Corps, treating wounded American soldiers in France. Since he had some college training in neurology and psychiatry, he was also assigned to treat brain injuries.

Dr. Marcus was badly injured while helping relocate an Army evacuation hospital and sent back to the U.S. for treatment. After recovering, he worked at an army medical facility in El Paso, Texas.

There, he created a clinic to diagnose and treat brain trauma and would later receive several commendations for his military service. His son said that among his patients was a Navajo code talker – a member of the unit who used their traditional language to transmit secret Allied messages in the Pacific and were later honored with Congressional Medals.

Following the war, Dr. Marcus completed his training at Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York, where he studied psychiatry, child psychiatry and psychoanalysis. He served on the medical faculty and in private practice.

After coming to New Orleans to work at Tulane, he established the Family Study Unit and also initiated community outreach efforts, working with the Children’s Bureau, Jewish Children’s Home, German Protestant’s Orphan Asylum and Associated Catholic Charities to better serve young patients.

According to Dr. Zeanah, Dr. Marcus also developed counseling programs for local schools and the pediatric wards at Charity Hospital. He is also credited with convincing state child protective services to enhance their efforts to counsel children in foster care.

His wife said his work with and on behalf of children was among his proudest achievements.

“He was also so dedicated to educating the public on the need for child psychiatry, which was new at the time, but so important,” she said.

Active in many professional organizations, Dr. Marcus was a founder and former president of the Louisiana Council for Child Psychiatry as well as the first president of the Louisiana Group Therapy Association.

The recipient of numerous professional awards, he was the author of six books and dozens of peer-reviewed papers and articles in medical journals covering topics such as sex therapy, marriage counseling, child psychiatry, family counseling, psychoanalysis and medical education.

“Irwin truly was brilliant,” said WWL-TV medical reporter Meg Farris. “Even in his last years, he was working on a solution to better protect professional athletes from head injuries. Even more than that, he was a true southern gentleman, a devoted doctor, father, grandfather and great-grandfather.”

Dr. Marcus’ first wife, Dorothy Elrod Marcus, was a speech therapist and social worker. She died in 1992.

He and Hill, who had been acquainted, went on a blind date in Jan. 1996 at Antoine’s Restaurant.

“We just talked and talked and talked, like we'd always been soul mates,” she said. “It was a wonderful night." The two were married four years later, traveled the world together and became fixtures at charitable, social and cultural events here at home.

Dr. Marcus also took up painting and sculpting, studying at the New Orleans Academy of Fine Arts and creating works honoring his wife, grandchildren and even family pets.

“Irwin was the only true Renaissance man I've ever known, the Da Vinci of our time,” said WWL-TV anchor Karen Swensen. “He was an artist, a sculptor, an inventor with patents to prove it, an author, a surgeon, a wounded warrior. He personified the Greatest Generation. But the best thing about Irwin was the way he loved – everyone, but especially Angela.”

Hill said one of her husband’s other loves was history, which he indulged by reading voluminous books about America’s founding fathers, military heroes and other icons. One of his last public academic events, at the age of 90, was at Monticello, Thomas Jefferson’s Virginia home, where he lectured and conducted a mock interview with an actor portraying the nation’s third president.

In addition to Hill, survivors include his three children: Dr. Randall Marcus, Sherry Leventhal and Melinda Marcus; eight grandchildren and 12 great-grandchildren.

Funeral services will be private.