NEW ORLEANS -- Gone are the days when the lobby of the old Times-Picayune building bustled with reporters rushing to and from assignments as readers dropped in to buy a classified ad or do other business.

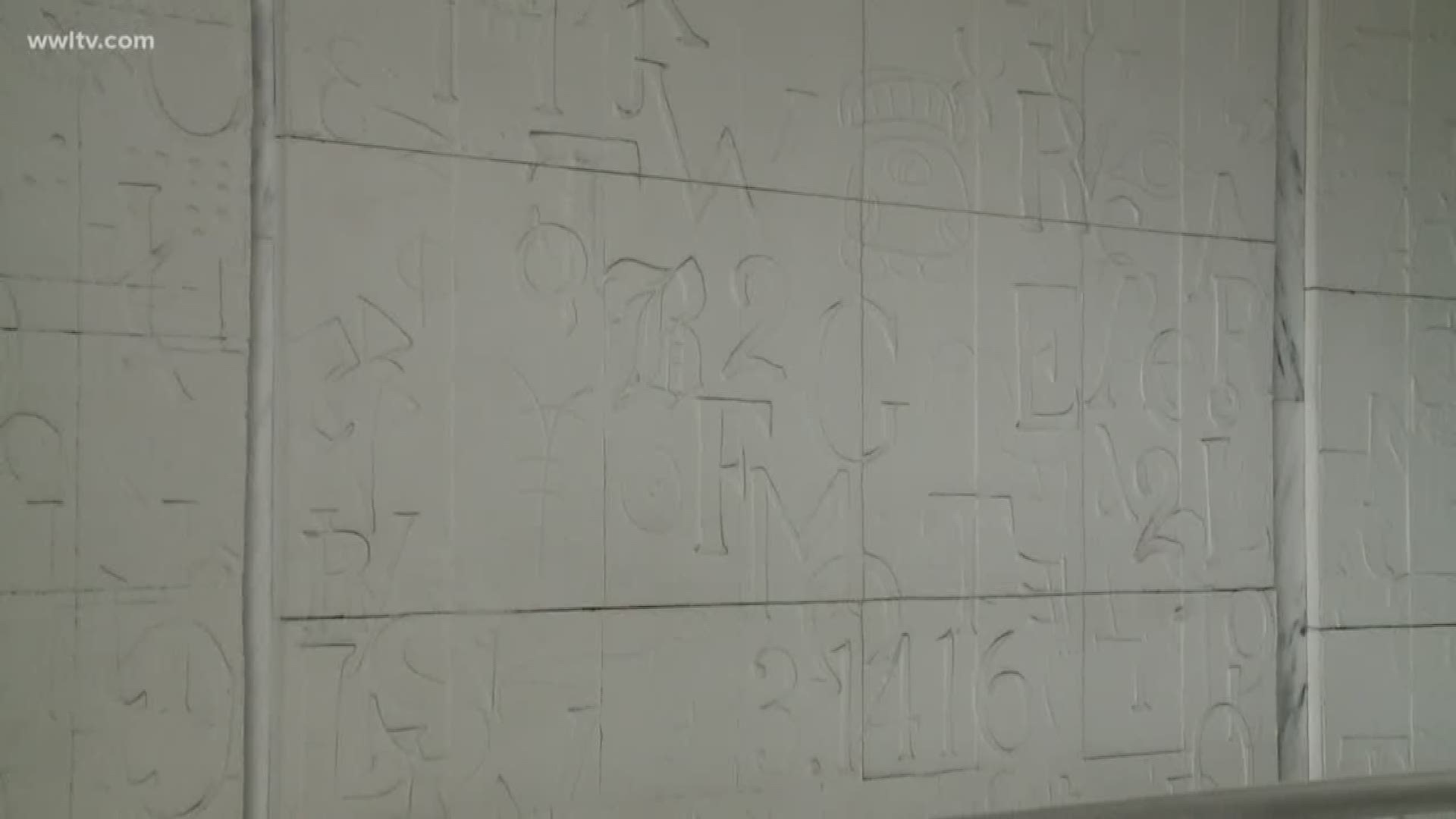

Instead, the massive three-story space on Howard Avenue is now covered in dust and debris as towering murals that depict the history of written communication are carefully removed from the walls ahead of the plant’s planned demolition.

In the coming weeks, the site where the day’s news was once printed on low-tech presses will make way for a sleek, high-tech driving range.

A chief concern among many in the city’s preservation and art circles was the fate of the plaster murals, known as “Symbols of Communication,” crafted by famed sculptor Enrique Alferez.

The building’s new owners -- a group that includes developers Joe Jaeger, Arnold Kirschman and Michael White as well as float builder Barry Kern -- vowed to save the murals, but plans about what would happen to them were scarce as details about plans to build a Drive Shack on the property were announced.

Peter Aamodt, senior development manager for Jaeger's firm, MCC Real Estate, said there was a lot of interest in the murals in Mexico, where Alferez was born, but that the decision was made to keep them in the New Orleans area.

“We haven’t selected anybody yet, but we have several interested parties,” Aamodt said.

After crews gently remove the plaster panels from the walls -- a process complicated by how they are anchored into the walls -- a conservator catalogs the pieces before they are stored in wooden crates.

Aamodt said there are “three or four” people who’ve expressed interest in the murals, but there’s not yet a decision on who’ll get them.

“Part of our desire is for them (the new owner) to display it,” he said. “Removing them now gives us the time to make the right decision.”

Luke Boehnke, with Montana-based Wolf Magritte, is in charge of the removal process. He said the height of the murals has presented something of a challenge.

“As you start to peel them away and you get more access around them it gets much faster” to remove individual panels, Boehnke said. “It would range anywhere from 20 minutes at the shortest to about two hours in some cases.”

Each panel weighs about 200 pounds. After each one is removed, it is cataloged, photographed and cleaned before it’s wrapped up and loaded into a wooden crate.

“We’re unsure about how long they’ll be stored, so they’ll be sitting in excellently-packed crates ready for the new owner,” Boehnke said.

The murals were commissioned to decorate what would otherwise be tall, drab walls in the newspaper building’s lobby.

“He (Alferez) knew that the elements used in any design must have some significance in the communication media,” read an article in a special section printed when The Times-Picayune and The States-Item, its afternoon counterpart, moved into the building in 1967.

“He used the hieroglyphics of the ancient Egyptians and the dots and dashes of the Morse code; he employed Mayan glyphs, cuneiform characters and alphabets from Phoenician, Roman and gothic times,” the article continues. “The Hebrew of the torahs, the graceful writings of the Arabs, and the fine brushwork of the Chinese and Japanese are all included as are the Braille symbols that enable the blind to read.”

All of that was included in 14 panels, several of which measure 37 feet tall and 8 feet wide.

The work to create the murals was tedious and, at times, nerve wracking, Tlaloc Alferez, Enrique Alferez’s daughter told The New Orleans Advocate.

She recalled how Alferez assembled the murals in a friend's warehouse. "Every hour a train came by on the Elysian Fields overpass, shaking and vibrating the unfinished piece, while my father lay on top of it to protect it," she told the newspaper.

She said the project was particularly personal for her father who fled his home country, without speaking a word of English, after serving in the Revolutionary Forces in northern Mexico under several generals including Pancho Villa.

“With nothing more than a Spanish-English dictionary, he taught himself English by studying the comics in the newspaper every day," she told The Advocate. "While at the Art Institute in Chicago, he radically improved his English before later coming to live in New Orleans.”

Once in New Orleans, Alferez, who died in 1999, created works that wound up everywhere from Charity Hospital to Lakefront Airport. Many were done for City Park during the Works Progress Administration.

Aamodt said he expects demolition of the Times-Picayune building to begin at the end of the month. If all goes according to plan, Drive Shack would open before the end of 2019.

Danny Monteverde can be reached at danny@wwltv.com.