NEW ORLEANS — As Louisiana comes to grips with its racist past, it keeps tripping over itself as it tries to correct historic wrongs.

The first example of this was an innocent mistake, but one that shows just how hard it is to root out misinformation.

New Orleans Mayor LaToya Cantrell and the New Orleans Regional Transit Authority both cheered Gov. John Bel Edwards’ posthumous pardon of civil-rights trailblazer Homer Plessy on Wednesday by tweeting a picture of the wrong historical figure.

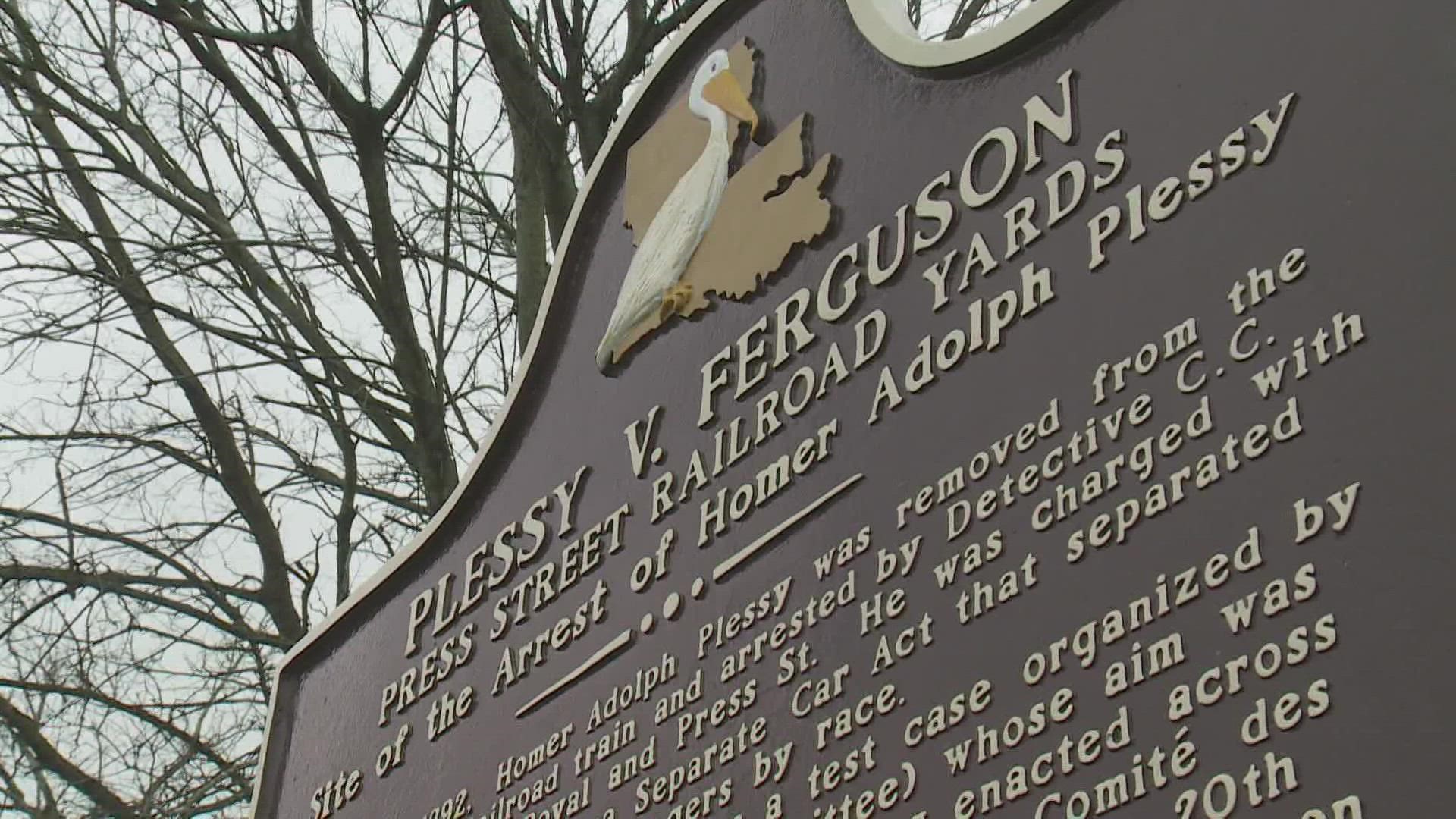

Both the RTA and Cantrell celebrated the pardon of Plessy -- a Black man who boarded a white-only rail car in 1892 and challenged his arrest all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court -- with a photo of P.B.S. Pinchback.

They can be excused, for they are far from the first to make this mistake. In fact, the Plessy and Ferguson Foundation was so frustrated by the proliferation of misidentification that it has an item on its website entitled, “No, Internet, this is not Homer Plessy!” It is linked to a 2017 Times-Picayune article explaining who the person in the photo really is.

Pinchback was a Republican elected to the Louisiana Senate during Reconstruction. He rose to the post of lieutenant governor and then served as acting governor for about a month after the elected governor was impeached in December 1872.

But here’s where so many have gotten the story wrong for so long: Pinchback was not the first Black lieutenant governor, nor was he the first Black acting governor in U.S. history. The man who preceded him in both of those posts was Oscar James Dunn.

Unlike Pinchback, who moved to Louisiana from Ohio during the Civil War, Oscar Dunn was born and raised in New Orleans. And yet, there was no public street, park or institution in the city named for Dunn until 2019, when IDEA Schools Oscar Dunn Elementary opened in New Orleans East.

And here’s where New Orleans has again stumbled this week in its efforts to right historic wrongs. Even as the city grapples with renaming streets and parks to honor Black heroes rather than slaveholders and Confederates, New Orleans Public Schools announced Oscar Dunn Elementary would close for lack of students.

A step in the right direction did come just last month, when the New Orleans City Council renamed Washington Battery Park in the French Quarter for Dunn.

But why would it take so long for someone of Dunn’s stature to be recognized like that?

The answer can be found in the lasting impacts of revisionist history. Even the 2017 Times-Picayune article that set the record straight about the misuse of Pinchback’s photo mentions Dunn as the lieutenant governor before Pinchback, but calls him “Oliver Dunn” and fails to even mention that he was Black.

Dunn was a dark-skinned “Anglo African.” He was popularly elected as lieutenant governor, which Pinchback never was. What’s more, Dunn had already served his own month-long stint as acting governor in July and August 1871, a year-and-a-half before Pinchback did.

It could be argued that Pinchback was “more” of the governor during his time as acting governor. Gov. Henry Clay Warmouth was impeached and completely removed from office when Pinchback took over for him. Warmouth was bedridden in Mississippi, but still technically governor when Dunn sat in for him.

But historian Brian Mitchell found that Dunn took several executive actions as governor, including appointing a judge and other key state officials while the White governor was bedridden in Mississippi, convalescing from a complication from surgery. By contrast, Pinchback did little during his time as the state’s chief executive. He was waiting to take his seat in the U.S. Senate in January 1873, something that never happened after the results of the 1872 election were overturned by Democrats.

Mitchell’s new book, “Monumental: Oscar Dunn and His Radical Fight in Reconstruction Louisiana,” released last year by the Historic New Orleans Collection, seeks to set the record straight about Dunn. It details his stand against corruption and in favor of integrating New Orleans’ public schools and police force during Reconstruction.

The book also suggests segregationists – the same ones who erected a monument to the massacre of the integrated police force by the White League, a monument that stood in New Orleans until 2017 – effectively erased Dunn from history because he was inconvenient to their narrative that Black politicians during Reconstruction were all corrupt and ineffective.

Pinchback, on the other hand, allegedly took bribes.

Makes you wonder, is that why he keeps popping up in our history books and on the Internet, whenever we should be seeing more heroic figures like Dunn and Plessy?