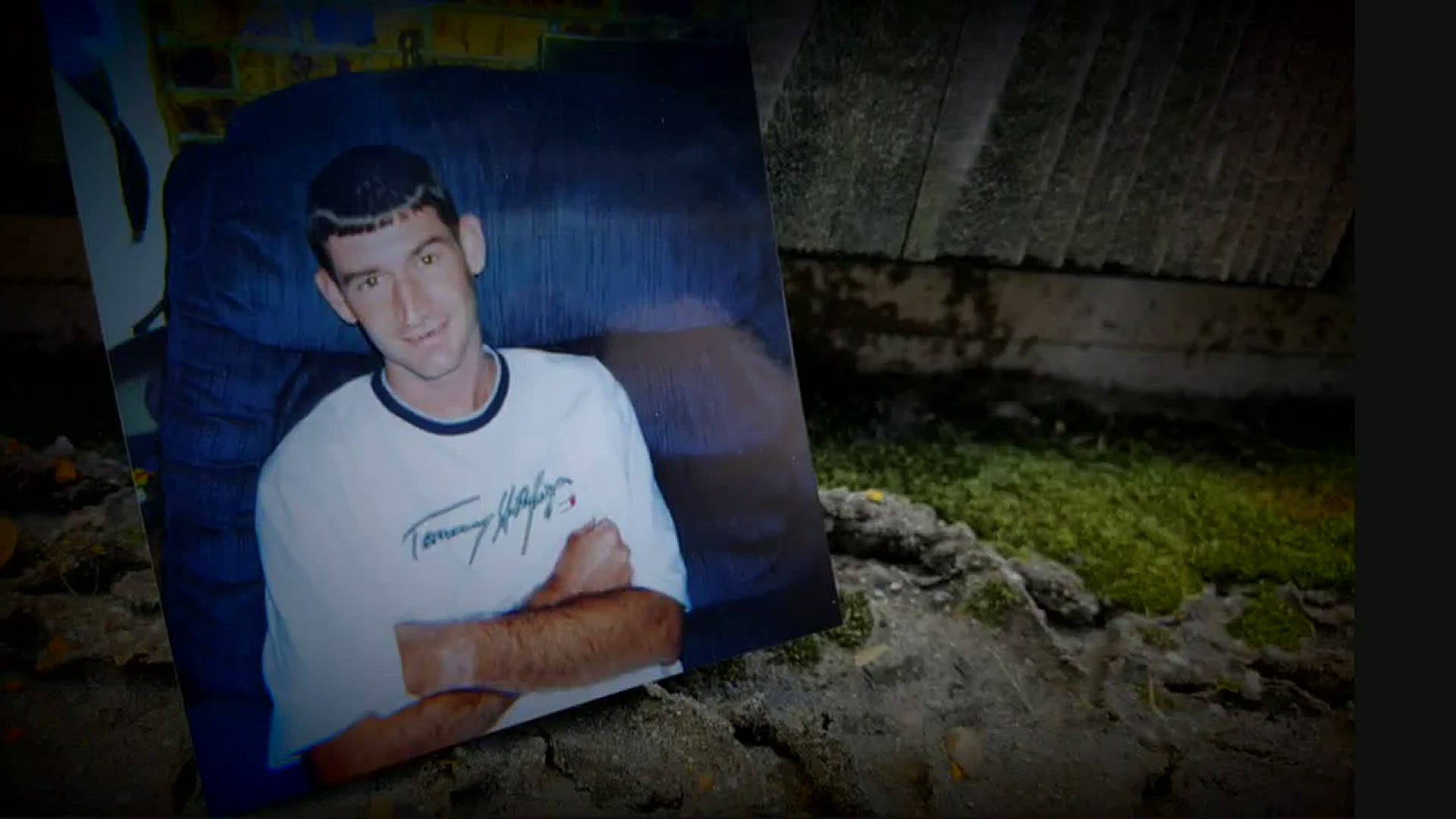

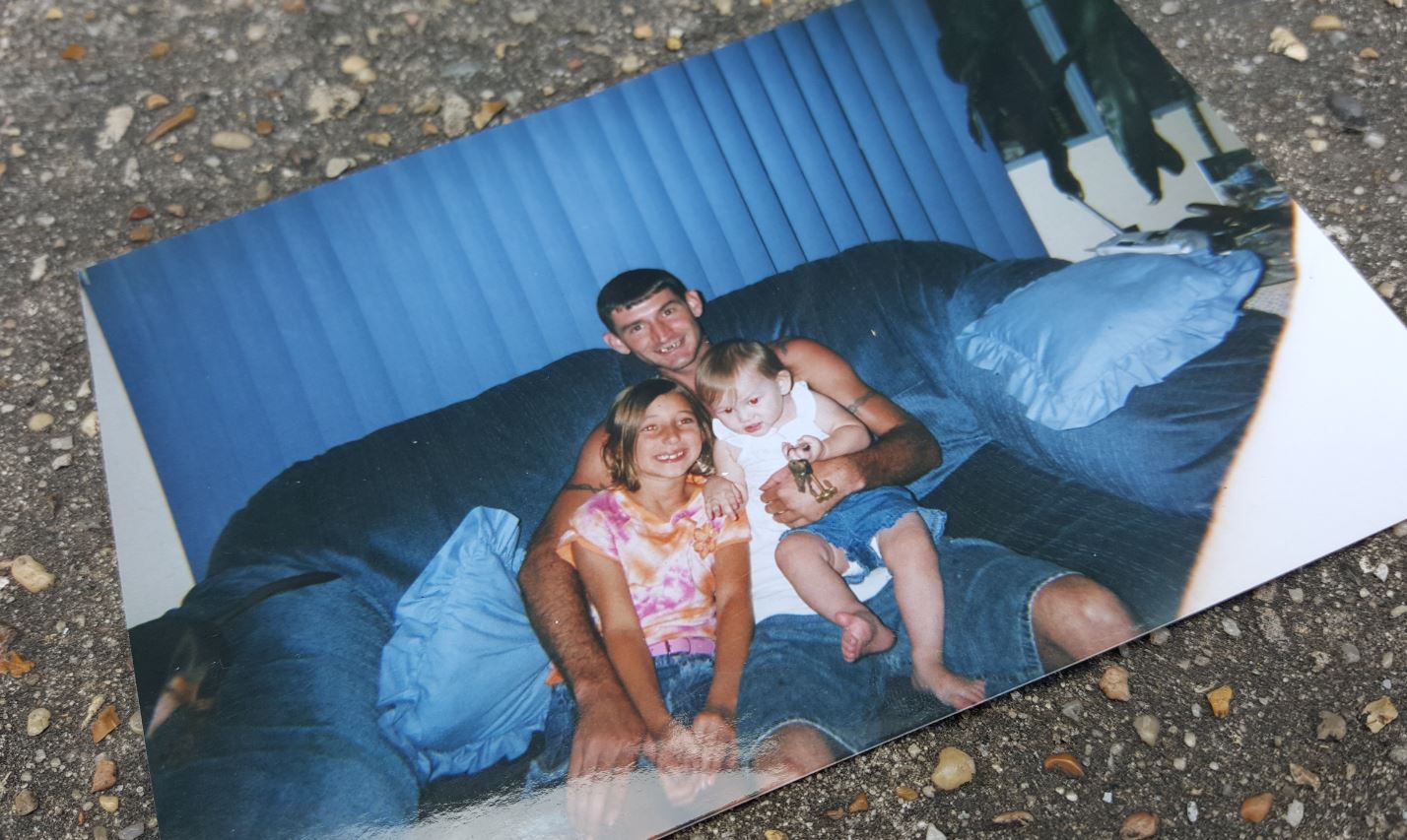

Blaine Millet loved to fish, usually from the boat docks near his home in Westwego. He even caught the occasional alligator. He was a family man with a son and daughter. He was known for his sense of humor.

He also was known for something less upbeat: a fierce heroin addiction.

“We tried everything,” his mother, Verna Millet, said. “We had him committed. We put him in rehab a couple of times. He stopped (using) for a while, but he kept going back to it.”

In December 2014, Blaine Millet buckled under the weight of his addiction for the last time. His body was found under a tarp at the Westwego boat docks, where he would often sleep after losing his home, his family and his long battle with the drug that had chemically hijacked his brain.

“He would cry to me that he was trying to get off of it, but he couldn't,” his mother said, choking back tears.

At 37, Millet became an early casualty of the heroin epidemic that is now sweeping New Orleans metro area, the state and, indeed, the nation.

Heroin overdoses leap past gun deaths in Orleans – JP numbers also staggering

In the city of New Orleans, overdose fatalities deaths aren't just breaking previous records, they're shattering them. In 2015, 63 people in the city died of heroin and opiate overdoses, according to the coroner’s office. That grim tally was obliterated in just the first half of 2016, when the deaths reached 81.

“That’s the first time in New Orleans history in which opiate overdoses has ever eclipsed the murder rate,” Orleans Parish Coroner Jeffrey Rouse said, citing the city’s six-month murder total of 67.

Surprisingly, New Orleans is only recently catching up to casualty figures Jefferson Parish has seen since 2013, Jefferson Parish Coroner Gerry Cvitanovich said. The number of opiate overdose deaths there has gone from 71 in 2013, to 73 in 2014, to 78 last year. Before that, the number of deaths ranged from 20 to 30, he said.

“Our heroin overdose deaths almost tripled about three to four years ago,” Cvitanovich said. “You’re seeing a lot of heroin use in upper socio-economic classes. You're seeing a lot more in the suburbs.”

By comparison, in 2009, there were 10 recorded deaths from heroin and opiate overdoses in the entire state of Louisiana.

No end in sight

“I am bracing for this to get worse before it gets better,” Rouse said. “We actually have people who are coming in dead to my office with hospital bands on their wrist. Meaning they overdosed, got revived in the emergency room, then walked right out and started using again. And ended up coming to me.”

Today’s heroin epidemic matches the spike in drug that was last reached during the 1970s, according to the Drug Enforcement Administration. But when it comes to the types of people using the drug, there is a new face of heroin.

Hard-core addiction is no longer confined to back-alley junkies. The modern-day epidemic is far more widespread, reaching middle-class suburbs, high school and college campuses, corporate offices.

“Addiction today knows no social class,” said paramedic David Hutchinson of New Orleans EMS. “I've dealt with people that were in the legal field, college students, junkies, homeless people. It doesn’t matter. It can be housewives or husbands.”

Over-prescription of pain pills helped pave way for heroin use

Experts say there are a number of reasons behind the surge, which encompasses not just heroin, but all opioids, the broader chemical category of drugs that includes prescription pain medicines such as oxycodone.

All of those substances are fiercely addictive, stimulating the brain’s pleasure centers through an unnatural release of dopamine. That chemical release can create a temporary sensation of euphoria, but it can also create harsh withdrawal symptoms for users who get hooked and try to stop.

One of the biggest factors behind the current epidemic is opioids themselves. For more than a decade, the medical establishment, fueled by a competitive push to gain patient satisfaction, overprescribed pain pills, creating a new generation of addicts

Just in the past few years, the experts have reversed themselves, recommending that physicians curb opioids. Law enforcement also has cracked down, targeting pill mills, doctor-shopping and other pain medication abuses.

For many users, the crackdown is backfiring. Unable to get the prescription version of opioids, some are turning to street heroin.

Cheap cost of heroin makes it enticing

“It's a medical problem, not a criminal problem,” said Dr. Jeffrey Elder, medical director of New Orleans EMS. “The problem is really addiction, and addiction is a public health issue.”

For users, not only is street heroin usually easier to find, it’s cheaper. Many local addicts say they can get a day’s dose for $20. Those historically cheap prices reflect a higher potency of the drug, meaning a smaller amount packs a bigger punch.

Not only is the drug itself more potent, synthetic derivatives – such as fentanyl –are often mixed in with heroin, turn every hit into a form of Russian roulette. Fentanyl, a synthetic opioid, is 20 to 50 times stronger than most street heroin.

“Over the last year, we’ve seen that heroin is being mixed with other drugs like fentanyl that are super-powerful,” said Dr. Peter DeBlieux, chief medical officer of University Medical Center. “The lethality of it, and the number of deaths, is something new.”

Also, the middle-class stigma of injecting drugs with needles has been fading, according to DeBlieux and other experts. As this taboo eases, new users from all backgrounds are experimenting with shooting up.

Two cases involving syringes recently made local headlines

On Sept. 1, Colin Mathison, son of Slidell Chief Administrative Officer Tim Mathison, 27, was captured on a cell phone video while passed out in a car in the Ninth Ward. Slumped back in the driver’s seat after crashing into three cars and knocking down a utility pole, a syringe was clearly visible in his hand.

Mathison was one of the lucky ones.

Four days later, in the same part of town, Justin Pohlmann died inside his car, a used needle telling authorities everything they needed to know. His father, St. Bernard Sheriff Jimmy Pohlmann, had helped him battle drug addiction for years, but even with Justin's wife expecting, the sheriff could not save his 30-year-old son.

“For those of us who sit at the receiving end of these drugs, we're terrified,” Rouse said.

“These are people, if we don’t treat, they’re going to die”

When it comes to heroin, death is usually the only part that is ever made public. Hidden from view are ravaged families, overcrowded jails, busy emergency rooms. For every fatal overdose victim, many more find themselves pulled back from death's doorstep. That trend can be seen in the number of times New Orleans first-responders are using the opiate reversal drug called naloxone.

According to Elder, there were 322 naloxone revivals by EMS last year. This year, they're on pace for 430.

“These are people who if we don't treat, they're going to die,” Elder said.

Some hard-core addicts, like Blaine Millet, never got a chance at revival.

According to his family, Millet suffered a painful, gradual decline. When it wasn’t heroin, it was alcohol. When it wasn’t alcohol, it was anything else he could get his hands on, his mom said.

But Blaine Millet was not a criminal, and his lack of a rap sheet proves it. Verna’s co-workers at the bail bond office where she worked saw a man with a medical problem: addiction.

“He kept busy, he worked. And he had ambition. He just had a problem he couldn't kick,” said Rob Dennis of Steve’s Bail Bonds.

The problem eventually spiraled out of control. Despite multiple trips to rehab centers, he kept using heroin. And to get heroin, he resorted to stealing from his family. But even after he was kicked out of the house and left homeless, Verna would seek him out where he slept at the boat docks, bringing him food and cigarettes.

The fateful call came on December 10, 2014. Blaine's body was found under a tarp at the docks, the same spot where he spent so many days fishing, and nights crashed out on heroin.

“We were waiting for a call any day, the way Blaine was going, the way he was putting us through everything,” Verna said. “I just never dreamed it would be that day.”

“It was sad, so said,” said Matt Dennis, another co-worker. “He was a good person...There was always hope, but on that day, hope ended.”

Last week, Verna Millet visited the mausoleum where he son is buried for the first time since he died.

“I'm trying to get some closure here. I'm really, really, really trying.” she said. “It’s very hard for me, I get so emotional. But if I can help others by sharing my story, then it’s worth it. May his life can be a lesson to other families who are facing the same problems.”