The FBI is actively investigating allegations of corruption against Lt. Gov. Billy Nungesser from his time as Plaquemines Parish president, according to multiple sources close to the investigation.

The investigation was first reported by The New Orleans Advocate. WWL-TV independently confirmed it and found that the probe focused on allegations that parish employees used parish equipment and materials to repair a private road and drainage canal at the entrance to Myrtle Grove Marina, which is owned by Nungesser and District Attorney Charles Ballay.

The FBI previously investigated Nungesser’s business dealings in the wake of the BP oil spill, when he was still parish president, but the inquiry produced no charges. The case sat dormant until last year, when allegations raised by civil lawsuits caught the eye of criminal investigators.

Nungesser says he’s used to what he calls a “witch-hunt” orchestrated by his political enemies, and insists he’s not worried about the latest probe.

“I respect the FBI and anything they want to look at, I’ll gladly share as I’ve done in the past,” he said. “But I don’t do anything wrong.”

The renewed federal investigation is being fueled by dueling investigations into possible corruption in Plaquemines Parish, one by the parish government and the other by Ballay’s district attorney’s office.

Stanley Wallace, who became the parish’s director of operations after Nungesser left office in 2015, said his workers produced photographs to back up their claims that they were ordered to fix damage on the private road leading into Nungesser and Ballay’s Myrtle Grove Marina in 2014.

Wallace said the parish workers replaced old culverts in a drainage canal running under the road, repaired a part of the road that had sunken in and laid limestone for 200 feet along the road where it enters the marina parking lot.

Just a block away, a parish road crosses the same drainage canal and offers direct access to the marina parking lot.

“So what they wanted to do, before (Nungesser) got out of office, they wanted to hurry up and do this one before they went over there and did the one for the parish,” Wallace said.

Ballay and Nungesser acknowledged the road is private and that parish crews fixed the culverts running underneath it, but said that’s part of the parish’s responsibility. Nungesser said the parish has a duty to maintain any canals that drain State Highway 23, the main route running along the west bank of the Mississippi River between Belle Chasse and Venice.

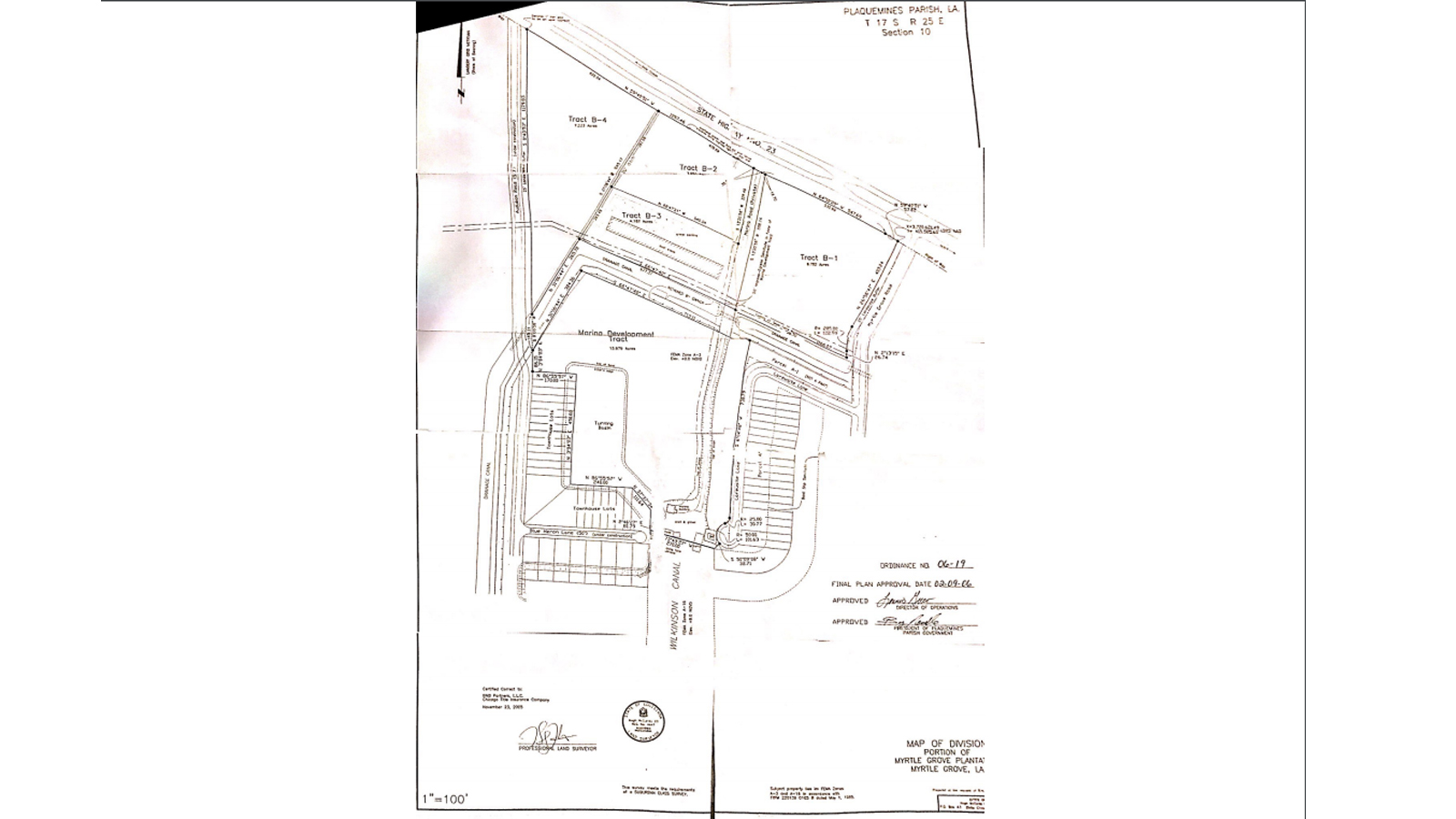

Parish records obtained by WWL-TV show that when the marina and surrounding properties were subdivided in February 2006, a land survey indicated the drainage canal would be retained by the owner, Citrus Lands of Louisiana, and the marina property would have a right-of-way to enter and exit over the canal.

Less than two weeks after it was subdivided, Ballay and Nungesser’s company purchased the marina property.

The work near the marina is one of more than 100 parish jobs Nungesser or members of his administration ordered to benefit private individuals, according to allegations made by the current parish legal team. But the parish’s attempts to file civil lawsuits to recover the taxpayer money spent on those jobs have caused their own controversy.

The man who succeeded Nungesser as parish president in 2015, Amos Cormier Jr., had his legal team file a civil suit against Nungesser in October 2015. But in January 2016, Cormier’s parish attorney, Joel Loeffelholz, wrote a memo to the parish council saying the lawsuit was filed without his approval and all its allegations against Nungesser were baseless.

The parish dismissed the case, but when Loeffelholz retired after serving a year as Cormier’s parish attorney, Cormier hired Robert Barnett, a north shore attorney who quickly resumed the parish’s investigation of Nungesser and his associates.

“They wanted to have whatever we knew on Mr. Nungesser,” said Blair Rittner, the former parish Land Department director who served under Nungesser and remained in the post after Cormier was elected.

Rittner secretly recorded a meeting last year with Barnett and provided the recording to WWL-TV. Barnett can be heard in the recording saying he is going to “expose an underbelly of the parish that’s not going to be pretty” and warning that he has affidavits signed by parish employees swearing that they performed public work on private property.

“Whoever’s fingerprints are on here, guess what? They’re personally liable for reimbursement, plus interest, to the parish,” Barnett tells Rittner, who resigned shortly after that meeting and took out an ad in the local paper saying he felt intimidated by Barnett.

With Barnett at the helm, the parish filed civil claims in state district court against three of Nungesser’s top aides and a former parish councilman, alleging they used their positions to benefit themselves, their companies or their family members. The defendants all deny the allegations.

Ballay, meanwhile, launched his own investigation, a criminal grand jury probe captioned in the court record as “State of Louisiana v. Public Corruption.” Ballay asked for records and computers from the parish government and subpoenaed testimony from the people helping Barnett, like Cormier’s former executive assistant, Marsha Lejeune.

“He had a grand jury going, and that was against us,” Lejeune said. “I was served with papers to go before the grand jury -- me and a few other people.”

Barnett and the parish legal team asked Ballay to recuse himself from the corruption investigation because he owns the Myrtle Grove Marina with Nungesser. Ballay refused, saying his investigation has nothing to do with the marina, although he declined to disclose the subject of his inquiry. A judge in Plaquemines Parish said Ballay did not have to recuse himself, but the state appellate court disagreed and sent the recusal request back to the district court for reconsideration.

Barnett previously worked for the Plaquemines Parish Council in 2010 and 2011 and filed 15 lawsuits against Nungesser on the council’s behalf, demanding that Nungesser turn over records or execute contracts and projects that the council had authorized but Nungesser opposed. Nungesser saw Barnett as his opponents’ attack dog.

“They hired him to find some dirt on Billy Nungesser,” Nungesser said, speaking of himself in the third person.

Barnett billed the parish more than $300,000 in a year and a half and was fired in 2011 when Nungesser’s allies gained a majority on the council.

Cormier, who lost twice to Nungesser in campaigns for parish president, brought Barnett back to Plaquemines in March 2016, but the parish president died in office a few months later. Now, Barnett works for the new parish president, Cormier’s son, Amos Cormier III, and has billed the parish nearly $250,000 over the last year. He says the civil lawsuits could recover millions of dollars for taxpayers, but the parish council is beginning to question that.

Council members have raised concerns about Barnett’s billing practices, noting that his costs were also questioned when he worked for fire districts in St. Tammany Parish and when he represented councilmen being sued in Gonzales.

Charlie Burt, who voted with a 6-2 majority to file the lawsuits last year, now wants to know if the expense has been worth it.

“I guess we are kind of, maybe not second-guessing ourselves, but we’re asking for more information and more documentation to make sure we’ve made the right decisions,” Burt said.

Even Benny Rousselle, Nungesser’s longtime nemesis and the biggest backer of the lawsuits, is growing wary of Barnett.

“I believe that he had good intentions, however I do have some concerns about the billing and about his actions,” Rousselle said. “I think some of the cases still have merit and that’s why it’s on the agenda in executive session to learn more about where we are in the process, but there is some skepticism about continuing to fund some of these cases.”

Cormier III now faces a dilemma. He said he believes the lawsuits seek justice and the recovery of misspent money. But he’s also wary that the parish government has had to slash 300 jobs since Nungesser left office, is more than $170 million in debt and recently considered declaring bankruptcy.

The council already voted earlier this month to hire another in-house parish attorney to lessen the need for Barnett’s services, for which he charges $175 an hour. And longtime Nungesser ally Kirk Lepine introduced an ordinance to kill the civil lawsuits altogether, saying that if criminal acts were committed, they should be left to law enforcement agencies.

The council is scheduled to take up the matter Thursday in Pointe à la Hache.