NEW ORLEANS — Forty-eight hours. A string of violent carjackings. Nine victims, all punched, beaten and dragged from their cars.

“The threat was very, very direct. I will hurt you badly,” one carjacking victim said. “I could be dead.”

“Just nailed me right in the face,” another victim said.

That was in 2019. Three juvenile suspects were arrested in that carjacking spree. Two were 16 years old, one 14. All had been through the juvenile justice system many times before.

“The revolving door of juvenile court crops its ugly head again,” former District Attorney Leon Cannizzaro said at the time.

Two of those young suspects ended up accepting responsibility in court and are now serving juvenile life sentences, locked up until they turn 21. But the third juvenile, one of the 16-year-olds, never went to trial, his case delayed by questions about his mental competency.

Just like Cannizzaro before him, New Orleans Police Superintendent Shaun Ferguson has recently railed against the revolving door for suspects, especially juveniles.

“We won’t see this revolving door end until our judicial system has become fully operational again,” Ferguson said. “It is very demoralizing to the officers.”

Carjackings becoming commonplace

In the past two years, carjackings have exploded. Based on the suspects who have been arrested, the majority are being committed by teenagers. In New Orleans, overall, carjackings are up 100 percent so far this year over last year, and up more than 300 percent from 2020.

“I don't know if this is a video game, Grand Theft Auto that they're playing in real life,” Ferguson said at a recent press conference.

Among the recent crimes: On Jan. 7, a car stolen with a five-year-old child still inside. Three days later, a victim was chased, shot at, then tackled in the street after he was carjacked, but refused to give up his keys. The thieves used a spare key to take off with his Ford Focus.

“Have our property taken and then threatened and shot, then yeah, we're all the victims,” said the victim of that violent car heist, video of which been frequently replayed on the news.

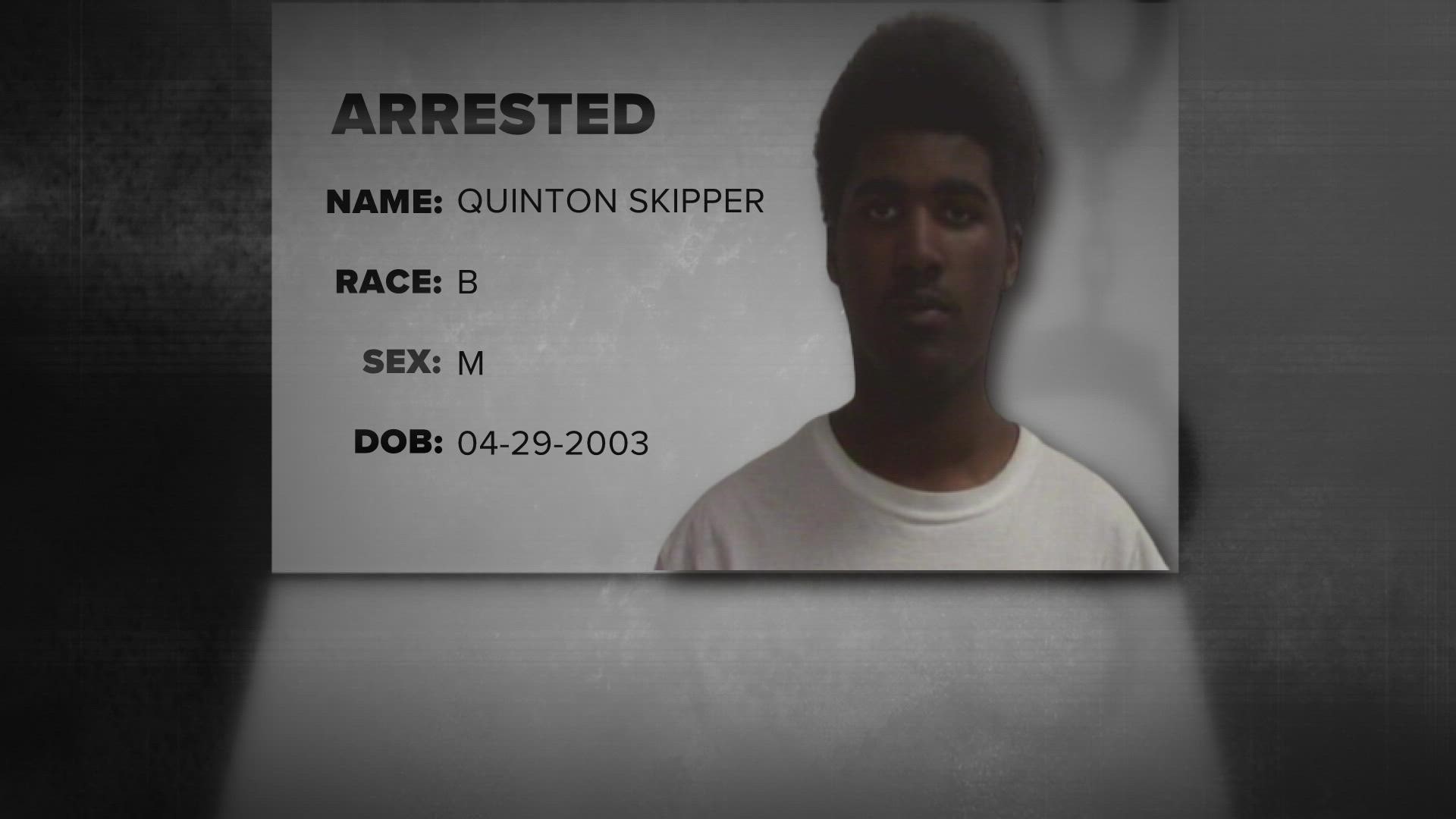

Suspect no stranger to system

In those two January cases and several other armed robberies, police arrested 18-year-old Quinton Skipper.

And now that Skipper is an adult in the eyes of the law, WWL-TV can reveal that Skipper is that third juvenile who was still awaiting trial in the 2019 carjacking spree. His alleged victims were never notified about the pending case. Nor were they told Skipper was out.

Quinton Skipper could be Exhibit A of the system's failure to deal with young carjacking suspects.

At a recent emergency meeting, City Council President Helena Moreno grilled Chief Juvenile Court Judge Ranord Darensburg about the release of juveniles accused of violent crimes.

“Why does there appear to be almost a revolving door for kids who are arrested for carjacking?” she asked.

“Well, we do not release kids who are arrested for carjacking,” Darensburg responded.

Despite Darensburg’ s statement to the contrary, Skipper was indeed released. Now he's facing more than a dozen new charges, this time as an adult. Darensburg later clarified that juvenile court doesn’t immediately release juvenile carjacking suspects upon arrest, but he conceded that the youngsters are not held indefinitely. He also admitted that resources for programs to help delinquent juveniles is scarce.

"Shock"

“I was blown away,” said Elizabeth Schindler, one of the victims in that 2019 carjacking spree. Back then she wanted to remain anonymous, but now she has come forward to speak openly about the case. She said she was still waiting to be called for Skipper's trial when WWL-TV told her he had been released and re-arrested as an adult.

“Imagine my utter shock when you reach out and you tell me, oh, turns out he's been out,” she said.

Schindler wasn't the only person dismayed that Skipper was released.

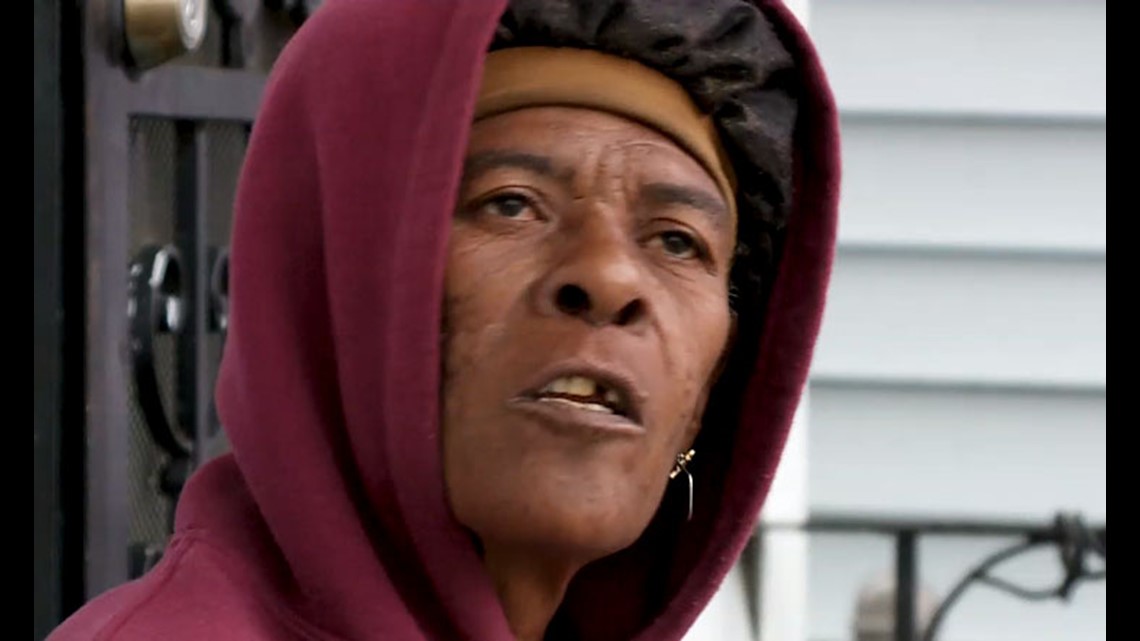

Cardella Skipper is Quinton's mother. She said she pleaded with juvenile justice authorities to provide help for her son. She said she received vague promises, but nothing happened.

Family wanted help

“They told the judge that they (Juvenile Justice Intervention Center) would prefer to give him back to his mom,” Cardella Skipper said. “Because they didn't know how to deal with him and they didn't want the responsibility. He didn't get the help that he needed.”

As his family admits, Quinton needed help. He his father died when he was a baby. He lost a brother to diabetes. After a mental illness diagnosis as a young teenager, he started getting into scrapes with the law. Then at 14, he suffered a life-threatening aneurysm.

One of Quinton’s older brothers, Garland, remembers that episode all too well

“Since the aneurysm, he had a problem,” Garland said. “My brother really hasn't been the same ever since.”

The next time Quinton was arrested after his hospital stay, things got worse.

“He got injured in jail. Somebody hit him to his head,” Cardella Skipper said. “He wasn't supposed to take no blow to his head.”

Quinton's mental state grew more volatile. His trips to juvenile jail became more frequent. But programs to curb his behavior did not.

“The system failed him,” Cardella said.

Garland did what he could.

“He used to try to listen, then it's like he'll waver back off,” he said. “If they would have helped him it would have been different.”

After getting released from the JJIC in the spring, Skipper got arrested again by early summer, this time in Jefferson Parish on cocaine and marijuana charges. While locked up, he got charged with battery on a correctional officer.

And yet again, Quinton Skipper was released, this time after his family posted bail. By Jan. 10, police say, Skipper was involved in five carjackings, armed robberies or attempted robberies.

The victim that police say was Skipper’s last before his arrest was the man in the frequently replayed video being tackled by his attacker as he was trying to run away. The man, who asked to remain anonymous, was unaware that Skipper had multiple carjacking charges pending in juvenile court.

“That is just overwhelmingly shocking,” he said. “If you're going to release these kids then they need to be released to programs that will help them. And if there are no programs that will help them, then what are we doing as a city?”

Schindler was also taken aback.

“They re-release this troubled child back into the environment that created the criminal to begin with,” she said.

Schindler said she hopes the system can find ways to help juveniles like Skipper. But in the meantime, after her boyfriend was carjacked himself on New Year's Eve, both went out and purchased guns for protection.

“It was very shocking and sobering thing when I told my parents,” Schindler said of her gun purchase..

“I just don't want to be that helpless like that on a daily basis,” her boyfriend, Blake Aguillard said.

Through all of trips to jail, all of the pleas for help, all of the victims, there was another voice that apparently was ignored: Quinton Skipper's.

“He said himself, jail saves people sometimes,” his mother said tearfully.

Quinton Skipper now faces up to 99 years in prison.