Brendan McCarthy / Eyewitness News

Email: bmccarthy@wwltv.com | Twitter: @bmccarthyWWL

NEWORLEANS- Residents of the nation's murder capital fear crime. They want more cops, more cruisers, more bad guys in handcuffs.

And over the past decade, as the city's police force has gotten smaller and smaller, the number of security districts has exploded.

These neighborhood security and improvement districts are everywhere in New Orleans. There are nearly 30 of them providing localized security right now, with three more on the Nov. 6.ballot. And several other neighborhoods are talking about starting their own.

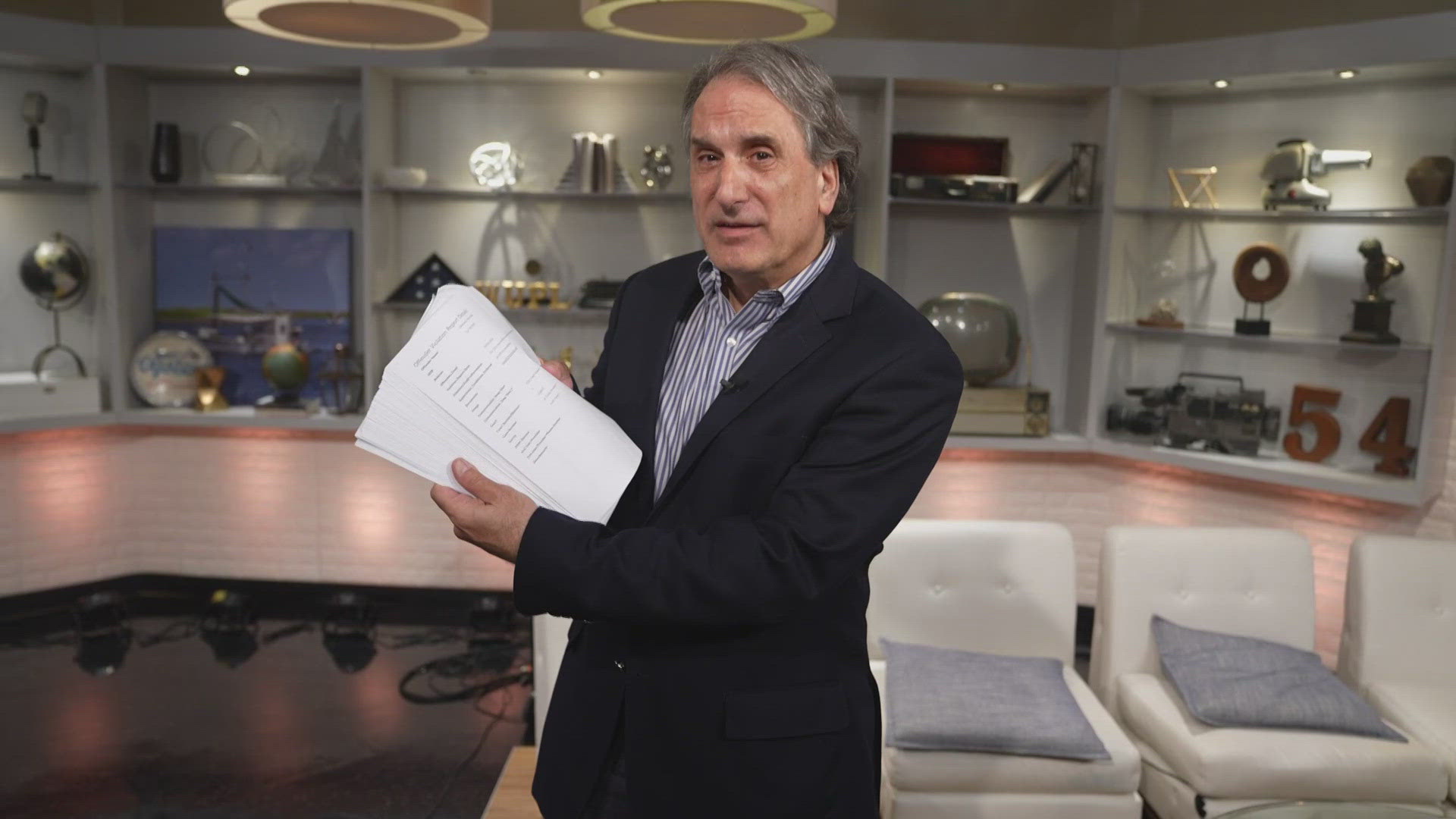

Louis Gurvich, owner of New Orleans Private Patrol, has several districts paying for his private security officers. And he anticipates more on the horizon.

'You are getting a private patrolman who has no other obligations. He is fresh. He does not work for the city,' Gurvich said.

'We must be doing something right. Because there are a lot more of them,' Gurvich said of the security districts. 'They seem to be growing every year.'

These self-taxing districts charge residents an annual fee for each parcel they own. It's usually hundreds of dollars. Some districts collect a millage, or a percentage of your assessed property.

These district are created when residents get state legislation passed, allowing for a neighborhood vote on the issue. They are almost always approved by voters.

A close review of Security District financial audits and filings reveals the groups wield a significant amount of power and money.

Some have million dollar budgets and have security staffs that rival the size of whole police districts. A majority of the neighborhood must vote to approve a district, but typically a handful of commissioners make the decisions. And there is little to no oversight.

Security district leaders and supporters say the patrols offer an extra layer of protection for neighborhoods that want it.

'People are concerned about security. They want to see more officers out there,' said Jim Olsen, of the Mid-City Security District. 'They want to see someone out there protecting their property, watching after them when they come home, whether it by daytime or night.'

Double taxation for citizens?

Critics say the security district system promotes inequitable policing and is rife with issues. They say these districts only serve to prop up a police department that is undersized.

'There is the issue of double taxation...Why am I buying stuff that I thought I paid for in taxes,' said Peter Scharf, a criminologist and professor at Tulane University. 'People are building their own fortresses, their own private security. It raises a lot of issues.'

The private patrols cost the average homeowner hundreds of dollars a year. And according to city records, through September of this year, citizens in select neighborhoods have paid roughly $6 million for security in these districts .

For that money, the whole City of New Orleans could pay for roughly 85 additional NOPD officers, the equivalent of an entire police district. Or they could pay the annual budget of the Covington Police Department, twice.

Earlier this year, when Fontainebleau residents talked about starting a security district, Jim Sehulster spoke up.

'I think there are better solutions than individual, small-sized assessments, for people to pay for these security details,' said Sehulster, a retired U.S. Marine colonel who previously worked at the University of New Orleans Center for Society, Law and Justice.

'If you took it and said this is how much total we've got and projected it to how many police officers we could have, how many new units we could be driving around in, we'd be saving money.'

Lack of standards

Eyewitness Investigates found no common standards among the security districts. Some pay off-duty NOPD cops to act as NOPD cops. Others pay private patrol officers. They don't have the arrest or investigative powers that the NOPD does; they are largely a visual deterrent.

The Upper Audubon Security District has a budget of about $200,000. Its legislation allows the district to charge each resident $500 for every parcel they own. In turn, the district provides a 24-hour private patrol that offers personal home escorts and residence checks.

The district board has to meet twice each year. They met last month, according to the board's president. The last meeting listed on their website is for 2010. Their website's message board has listings for missing cats, dogs and a turtle.

Then there is the much larger Mid-City Security District. It has a budget of roughly $1 million. And it publishes financial numbers and crime stats on their website. The district even hired a public relations firm to make their newsletter slick.

Olsen, the group's president, likened the district to a 'gated community that already has police protection.'

'I think there are a lot of people who don't realize what their purpose and what their function is,' Olsen said. 'They look at the parcel fee that they are charged just as an extra tax. And they question what the benefit is, what they get from that. That's why we are trying to promote what Mid-City Security District actually does during the course of a month, in order to let people know the extra protection they are getting, the extra crime prevention, the extras that these patrols afford us.'

Olsen's district has a roster of about 70 officers they can call on. The off-duty NOPD cops typically work four-hour shifts. And usually, the district has three or more officers on patrols. They are working to increase that and hope to have five cops working simultaneously next year. Olsen said the group hopes the security district cops can start doing more undercover, surveillance work for the district.

The Mid-City Security District purchased four vehicles for its officers. The vehicles stand in stark contrast to the NOPD's beat-up fleet.

Though the district buys the vehicles, the city is on the hook for insurance, maintenance and gas.

Also, the cops on the Mid-City district patrol are given cell phones in order to answer calls. About 20 times a month, a citizen calls them directly, whether for an escort or another type of issue, Olsen said. Otherwise, the security district cops are helping answer service calls to the NOPD. They average about 1,500 NOPD calls a month, Olsen said.

In the Touro-Bouligny Security District, board members chose to go with a private patrol group.

'We went the NOPD route when we started,' said member Charles Franks. 'We discovered that they had their work to do and it often overshadowed what we needed them to do. You don't have the control over the NOPD. With private security, you can dictate, pretty much tell them what you want to do.'

Franks said there is an extra level of responsiveness, and accountability, that comes with a private security force.

'We set guidelines, tell them to meet us places, have them follow us home. They are amicable to helping out,' he said. 'It's extra special treatment you get...They are accountable, they work for us.'

Different districts, different priorities

The priorities of the different districts vary widely.

In late September, more than 20 people gathered in the rectory of St. Dominic church for the Lakeview Crime Prevention District meeting. Car break-ins are the talk of the night. There were 33 that month. NOPD Sgt. Joe Bouvier, who is assigned to the security district, said 25 of those cars had unlocked doors.

Board members grimaced, shook their heads. 'This is outrageous,' one said. Bouvier said he's been running four Lakeview Crime Prevention patrol cars at night, three in the morning hours.

Board member Val Cupit cut to the chase: 'What can we do, from a manpower aspect?' She and others want to see blue lights, boots on the street. 'How can we get more?' she asked.

Bouvier shrugged. The board talked about hiring more off-duty cops, perhaps in spurts when they see spikes in break-ins or burglaries. Cupit and others suggested that they could try to coerce NOPD higher-ups to designate a task force, some type of pro-active unit, 'maybe SWAT,' to help Lakeview out.

Part of the problem, they reckoned, has to do with the NOPD's crime lab. The NOPD pulled 23 fingerprints from some of these break-ins. But the crime lab hadn't processed them yet. Lakeview wants results, wants answers.

'Can we buy an extra crime lab person?' Cupit asked. Everyone looked to the attorney on the board. He shook his head disapprovingly.

The group decided to focus on an advertising campaign, television ads, to remind residents 'Lock It or Lose It.' Someone made a motion to approve it. But one board member stepped in. He said that it would send a mixed message about crime in Lakeview. They wouldn't want people to think crime is rampant and break-ins are just happening here. The motion is amended. The awareness campaign should be city-wide, not just in Lakeview. The motion passed.

The decision-makers on these boards are mostly volunteer neighborhood leaders, including political appointees. The exception is Shelley Landrieu, the mayor's sister. She has been a paid administrator for the Garden District Group, one of the oldest districts, since about 1998. She now runs four security districts, and reports directly to those respective boards.

'I think because the city is under financial restraints as we know,' Landrieu said, ' I think people are just taking things into their own hands like they have done in lots of areas, especially after Katrina.'

'People wanted to sort of control their own destiny as best they could,' Landrieu added. ' I think security districts are one way to try to make the neighborhoods feel safer and feel like they are more of a community.'

Some feel the private security is doing the job the NOPD isn't.

Addie Hammond, 73, owns several properties on the corner of Carondelet and Seventh Street. Some are in the Garden District Security District, some aren't.

'They patrol pretty good,' Hammond said of the private patrol. 'They are around here all the time.'

Still, she feels overtaxed. And if not for the security district, she said she'd rarely, if ever, see law enforcement.

'Ha,' Hammond said. 'Unless you call the 911 first.'

Privatized officer overtime

Though residents may love the extra security presence, the U.S. Justice Department has said there is inequitable level of policing in the city.

The feds slammed the practice of off-duty police details, calling it privatized officer overtime, with more cops working in areas with the least crime, and fewer cops working in the parts of the city with the greatest crime issues.

In a report, the DOJ noted: 'When NOPD is able to do its job effectively, no community should feel that it has to pay extra to be secure.'

Police Superintendent Ronal Serpas offered little opinion when asked about security districts.

'I think that the people of neighborhoods make choices for themselves, and that's as democratic as it can get,' Serpas said. 'If they believe they need more service than what is being given to them through their general tax obligations and their property tax, they make those choices.'

Serpas, himself, moved into a neighborhood that has private patrol. Asked whether he would vote to renew the private patrol when it comes up on the ballot, the chief said he wasn't sure.

As the number of security districts continue to rise, the number of NOPD officers on patrol is dwindling. On some nights, in some districts, it's down to three cops answering service calls and 911 emergencies.

Stay tuned for another Eyewitness Investigates report that examines just how many officers are out in the streets, responding to emergencies.