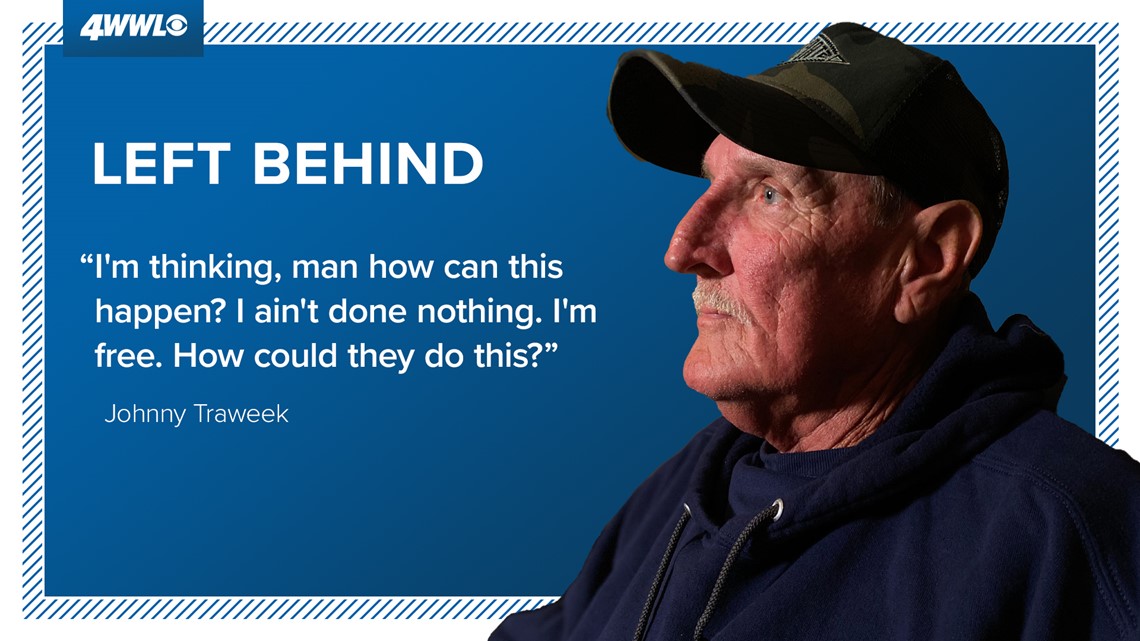

NEW ORLEANS — A fight over a sandwich landed Johnny Traweek in jail. After serving seven months waiting for trial, the 67-year-old agreed to plead guilty and put his nightmare behind him.

Traweek was homeless, but even the streets seemed better than another night behind bars. The judge wished him luck.

“The last thing I asked him was, ‘Will I be out tonight?” Traweek recalled. “And he said, ‘You most definitely will be out tonight.’ ”

Waiting for authorities to process his paperwork, Traweek gave away his meager jailhouse belongings, including his bed roll and prison sweats.

“I gave everything I had, even toothpaste, soap, everything,” he said.

But when breakfast was handed out the next morning, Traweek was still locked up.

“I'm thinking, man how can this happen? I ain't done nothing. I'm free. How could they do this?” Traweek wondered.

The day passed, and the next. And the next. But Traweek didn't go anywhere.

“I was like, man, what in the heck is going on? I'd be up all night, just pacing back and forth,” Traweek said.

Twenty days later, Traweek was finally released. He pleaded guilty on May 2, 2018, but wasn’t freed until May 22, records show.

His is not an isolated case. Hundreds of state inmates do time beyond their sentences each year, due to a combination of complex sentencing calculations, lack of technology, and poor communication between court clerks, jailers and the Louisiana Department of Corrections.

New Orleans Chief Public Defender Derwyn Bunton said his already overburdened office spends countless hours fighting for prison releases that everyone has agreed to.

“It happens every day. It happens all the time,” Bunton said. “Like I said, these are real folk who are now basically, in a way, taunted by a system's inefficiencies.”

Traweek's release was delayed because paper records from the Orleans Parish Sheriff’s office had to be hand-delivered to Baton Rouge. When public defender Stas Moroz fired off emails to speed the process, one response from the sheriff's office ended with, “He has to wait!!!!”

“Imagine being locked in a cage and not knowing when you're going to get out,” Moroz said. “The psychological toll is devastating.”

“These are people,” Bunton said. “These are husbands, fathers, mothers, aunts. This isn't your car you drop off at the shop.”

Traweek is now one of at least 10 former inmates suing state and city officials over chunks of their life they can never get back.

Attorneys Casey Denson and William Most represent Traweek and five other inmates, some held much longer than 20 days.

“They're held days, weeks, months, sometimes longer,” Most said. “We have one client who was held 589 days past when everyone admits he should have been released.”

Denson said there is a much bigger Constitutional issue at stake.

“This is such a fundamental fairness issue, which is at the core. Liberty is one of the most important values in our society,” Denson said.

In the lawsuit filed by the inmate who was held for an extra 589 days, the attorneys claim a two-year sentence was mistakenly changed to five years by a Department of Corrections clerk. The suit includes the inmates' calendar entries with expected release dates crossed out, and births, deaths and other family milestones he missed.

“It's hard to be in prison. But it's much harder to be in prison when you know you should be free,” Most said.

The Orleans Parish Clerk of Court said it has ironed out its paperwork problems and is currently up-to-date in all of its notifications.

But two other parties to some of the lawsuits – the Department of Corrections and Orleans Parish Sheriff’s office – declined to comment.

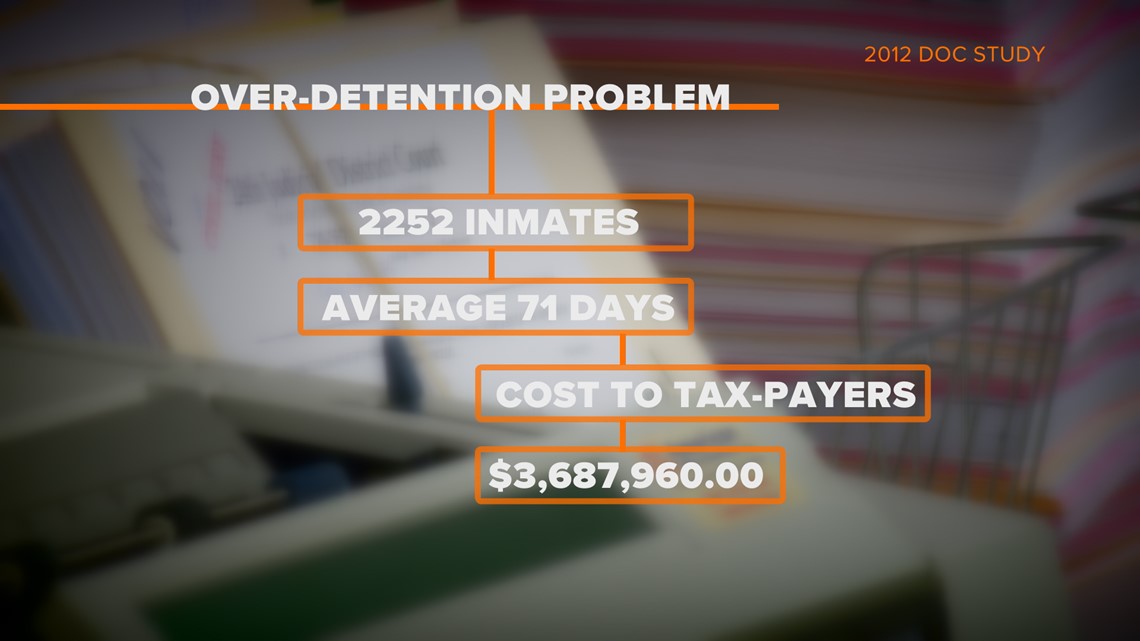

Officials have known about the over-detention problem for years. An internal DOC audit in 2012 showed that more than 2,000 inmates were held an average of 71 days beyond their release dates.

The problems is not just a burden for inmates. Taxpayers shell out more than $3.6 million annually to care for inmates beyond their release dates, according to the 2012 report.

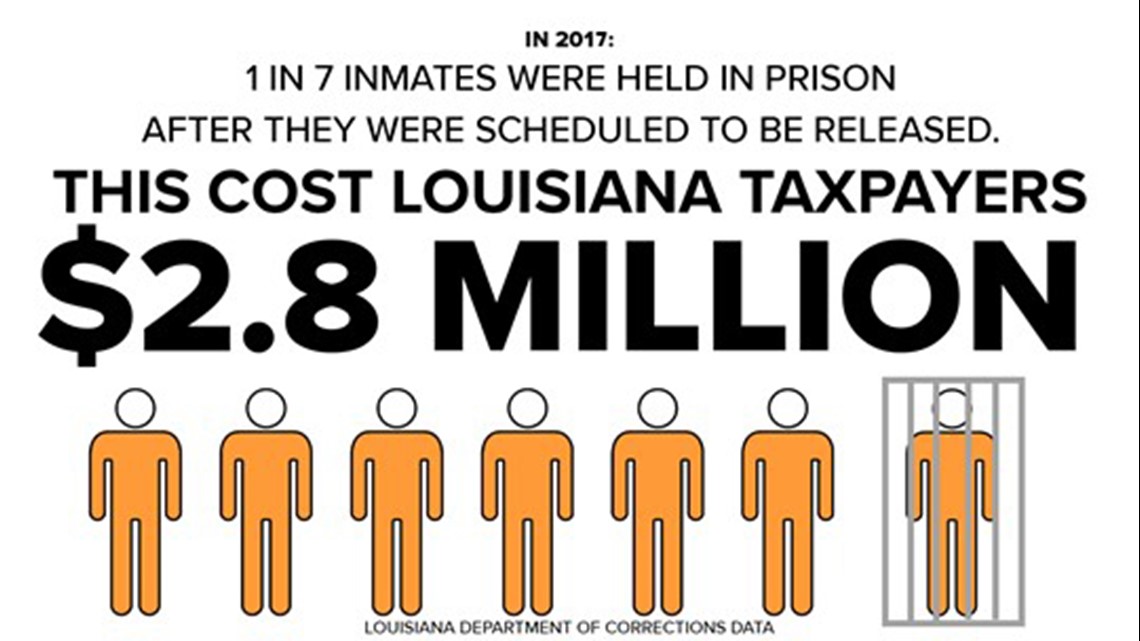

Despite efforts to do better in recent years, the department in 2017 pegged the costs of over-detainees at $2.8 million dollars for housing alone, not even considering medical and other costs.

A 2017 legislative audit highlighted the problem, but a follow-up report in 2019 found the issue had not been fixed. In Feb. 2019, for example, an internal DOC audit found 231 inmates were over-detained an average of 44 extra days.

As chair of the state sentencing commission, New Orleans Criminal Court Judge Laurie White is trying to find a fix. She says the system is bogged down by complex layers of laws calculated by low-level DOC employees using outdated technology.

“It has to stop. It has to change,” White said. “I call it the abacus and full moon method. Apparently you have a couple of people who have to sort through it, almost like some sort of medieval calculation.”

At a legislative hearing in December, State Department of Corrections Secretary Jimmy LeBlanc found himself on the hot seat over the issue.

“We've had a number of complaints to be just frank with everyone in the room,” said then-House Judiciary, Rep. Chairwoman Katrina Jackson, D-Monroe, who now serves in the State Senate.

“There is no electronic system integration among these three entities, the DOC, the clerks and the sheriffs,” LeBlanc admitted to the house panel. “I want to stress that it's not as simple as applying a formula in a time period and producing a release date.”

One major reason for the problem is the uniquely high percentage of state inmates serving their time in parish jails. Louisiana houses more than 50 percent of inmates in local lock-ups, compared to fewer than five percent in other states.

While LeBlanc and other officials were unanimous in saying that reforms are needed, they didn't offer much in the way of solutions.

“Changes are clearly required and we can agree that no person should be held beyond his or her proper release date,” LeBlanc said.

While LeBlanc did not offer remedies, he said his department has applied for a $1.2 million federal grant to find “a web-based portal for the use by our sheriff’s and clerks to submit paperwork and improve efficiency and accuracy.”

Department attorney Jonathan Vining used a PowerPoint presentation to explain the difficulty of the task as currently structured using mostly paper records.

“It's hard. It's very hard,” Vining said. “And some of these people don't have, not some, a lot don't have a lot of experience.”

In a written statement, a DOC spokesman said the department requested the formation of a legislative committee that is bringing together all the agencies involved to search for solutions.

“The purpose of this joint committee study is to allow for DOC to work with its partners, including the sheriffs, clerks, D.A.s, District Judges, and public defenders, to identify opportunities to improve the process,” the spokesman wrote. “We would encourage anyone who has ideas or input to improve the process, to provide that information to the joint committee.”

Of the New Orleans agencies involved, the clerk of criminal court said his office is caught up on all its paperwork and is determined to stay up-to-date. The Orleans Parish Sheriff’s office declined comment due to the pending lawsuits.

For those representing inmates left behind when they should be free, that's not enough. Those advocates point to the fact that 49 other states have figured it out, mostly through centralized and computerized systems of calculating prison terms.

“We don't know of any other state that has a problem even remotely as bad as Louisiana's,” Most said.

Meanwhile, the multi-million dollar price tag to taxpayers is growing, especially with several of the inmate lawsuits heading to trial.

“Those lawyers (defending the state) aren't cheap,” Bunton said. “You're talking about lawyers who are going to run between $250 and $500 an hour for what is probably a $20-an-hour staff fix.”

“It's penny foolish and pound foolish,” he said.

In a recent motion for summary judgment on behalf of Rodney Grant, who was held in the Orleans Justice Center 27 days after his release date, Most argued that the state’s lack of action amounts to “deliberate indifference.”

“The DOC here usurps the role assigned to judges,” Most wrote. “It rejects the black-letter law that a judge decides the length of an inmate’s sentence. It has decided, under Secretary LeBlanc, that an inmate’s sentence continues until the DOC gets around to performing his time computation.”

► Get breaking news from your neighborhood delivered directly to you by downloading the new FREE WWL-TV News app now in the IOS App Store or Google Play.