Secret recordings, police interviews raise more questions about Archdiocese's reaction to abuser

“They can’t even do something as simple as put somebody on the list who admitted it,” said the victim.

WARNING - this story includes details of sexual abuse that will be difficult for some viewers to read/hear.

More than 10 months after he pleaded guilty to child molestation and after his victim received a substantial financial settlement, the Roman Catholic archdiocese of New Orleans has at last acknowledged that deacon VM Wheeler was a credibly accused child molester.

Wheeler, a prominent attorney and church benefactor who died this spring, was ordained in 2018 by New Orleans archbishop Gregory Aymond. Over the next four years, Wheeler would be accused of molesting a 12-year-old boy in the early 2000s, suspended from ministry, arrested on suspicion of raping the child, charged with aggravated sexual battery, accused in a lawsuit of trying to pay the victim $400,000 to stop working with police and – in December 2022 – pleaded guilty to indecent behavior with a juvenile.

Still, Aymond would not make Wheeler the 78th cleric on his archdiocese’s list of clergymen faced with credible allegations of child molestation until this month, after WWL-TV and the Guardian questioned his omission from the roster in August and settlement of the victim’s civil suit against Wheeler’s estate in September.

Now, the station and newspaper have obtained police interviews and secret recordings that raise fresh questions about why Wheeler wasn’t added to the list much sooner, how the archbishop and other church leaders handled repeated complaints against Wheeler, and why prominent Catholics with close ties to Aymond were able to try to intimidate a victim whose identity the church was sworn to protect.

The new information starkly illustrates the amount of pressure those loyal to the church can exert on those speaking out even when they are relatively well-heeled themselves – and as the archdiocese continues roiling from a decades-old clerical molestation scandal that forced it to file for bankruptcy protection in 2020.

Recently, the victim disclosed his identity publicly to the Guardian.

LOSING FAITH PART 1

*A warning - this story includes details of sexual abuse that will be difficult for some viewers to hear.

Victim comes forward

The victim is Mac McCall, 34, the child of Mary Lou McCall, a former journalist and host of a Catholic television show, and John Young, the ex-president of Jefferson Parish and once a candidate for lieutenant governor of Louisiana.

In an interview with WWL-TV and the Guardian before Wheeler’s name was added to the official list of accused abusers, Mac McCall blasted the church for its handling of the broader abuse crisis and his claim against Wheeler in particular.

“They can’t even do something as simple as put somebody on the list who admitted it,” he said.

After Wheeler took a plea deal in December 2022 to serve five years’ probation for indecent behavior with a juvenile, Mac tried to meet with Aymond to ask him to add Wheeler’s name to the official abuse list. Clerical molestation survivors often draw validation from seeing their abusers’ names added to the list. And Mac had told church officials that seeing Wheeler listed would mean a lot to him

Mac recorded audio of his visit to the archdiocese offices. And in the recording, another priest once accused of child molestation in since-dropped litigation, John Asare-Dankwah, can be heard waiting for a scheduled meeting with Aymond.

So the archdiocese’s attorney, Susan Zeringue, comes out to meet with Mac instead.

'We don't interfere'

When Mac asks Zeringue why Wheeler isn’t on the list, she says the church “won’t act … until the final criminal proceedings are done”.

When Mac says they are done, she asks if he has a pending civil lawsuit against Wheeler. He says yes – and she adds a new reason they can’t add Wheeler to the list.

“Because we don’t interfere with ongoing civil or criminal litigation,” she said. “Whenever that’s going on, we take a step back.”

However, in at least two other recent cases – Patrick Wattigny and Brian Highfill – Aymond added priests to the list while criminal or civil cases were pending against them.

In August, a church spokesperson gave WWL-TV yet another reason Wheeler wasn’t added to the list: because the abuse happened prior to his ordination. However, the second priest on the original list, Paul Calamari, is on there for alleged abuse in the 1970s, prior to his ordination in 1980.

Aymond’s statements to police authorities investigating Wheeler in 2020 are also contradicted by Mac and his family’s recollection of events.

Mac said he and his father first met with Aymond in September 2018, less than three months after Wheeler was ordained, to report that Wheeler had fondled Mac’s genitals in a movie theater when he was 10 or 11 years old. Aymond had called the meeting after he said he heard rumors that something inappropriate may have taken place between Wheeler and some members of Young’s family.

Mac said Wheeler had threatened him to never come forward and in 2018, Mac was still afraid to tell his father or Aymond about the showers Wheeler took with him or the oral sex Wheeler performed on him. He wouldn’t give those full details until July 2020 – but he questioned why Aymond did nothing to investigate his first complaint in 2018, which explicitly mentioned fondling.

In an interview recorded by police, Mac’s father tells a similar story to detectives: that his son told Aymond that Wheeler had touched his genitals and the archbishop didn’t appear to think it rose to the level of abuse.

Young said, “I remember the archbishop mentioned it as grooming activities,” which the church purports to condemn but does not consider as fitting the definition of abuse. Young added: “I thought it was a little more than grooming.”

But in his own interview by detectives, Aymond has a different recollection of the 2018 complaint.

“Not only did he say there was no sexual activity, abuse, but it was also very clear that neither he nor his dad wanted to participate in any kind of investigation,” Aymond said on a recording of the conversation, which – like the others – were obtained through a public records request by Richard Windmann, president of the victims’ advocacy group Survivors of Child Sexual Abuse, and shared with WWL-TV and the Guardian.

LOSING FAITH PART 2

In a statement to WWL-TV, Aymond said, “I told the officers the truth as told to me by [Mac] in the presence of his father, John Young.”

Asked by police if he believed Mac’s claim, Aymond said he did – but with a caveat.

“However, now the story’s changed three times,” the archbishop said. “So I’m not saying I don’t believe him, but I also want to say, respectfully, that his past in terms of drugs and alcohol and being in a psychiatric hospital and all – which I didn’t know at the time – I think that that plays into it.”

Mac has since said the archbishop’s comment about his acknowledged past drug and alcohol abuse was like “attacking somebody and then blaming them for the injury”.

“A lot of victims and a lot of survivors have drug issues because they’re trying to self-medicate because they were abused,” he said.

An earlier warning

Meanwhile, Mac’s mother told investigators she had gone to church authorities with concerns about Wheeler long before all that.

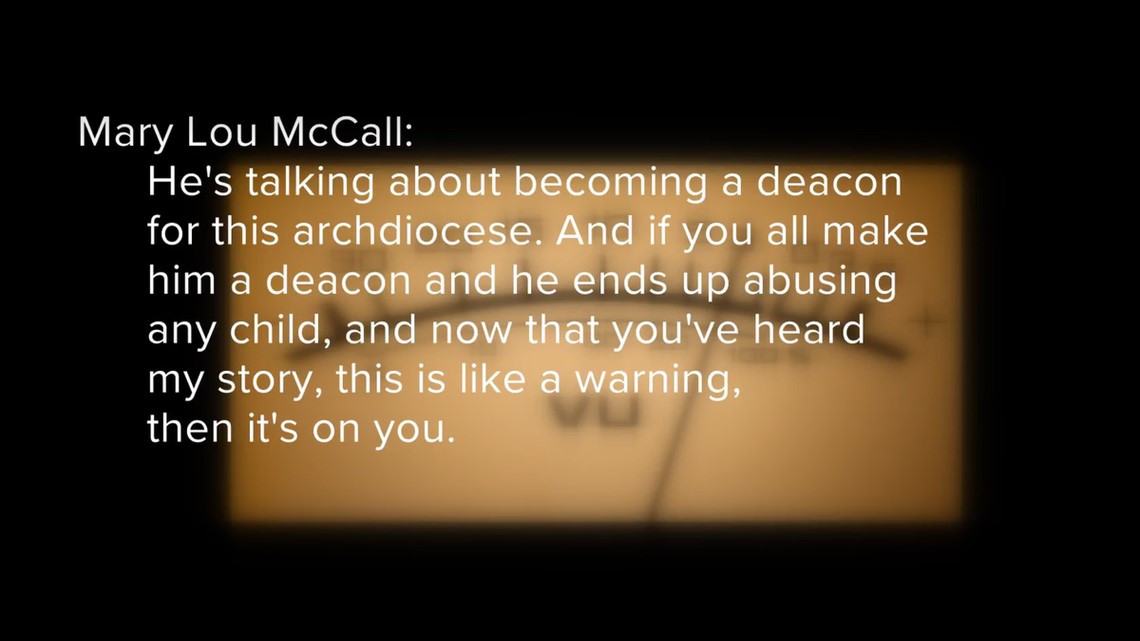

Mary Lou McCall said Mac’s older brother, Johnny, got back from a ski trip to Utah in 2002 and reported that Wheeler had made him sleep in the same bed with him. She said she immediately reported Johnny’s statement to retired New Orleans archbishop Philip Hannan – with whom she was making a documentary at the time – and Jim Swiler, the head of the deacon-training program that Wheeler aspired to join.

“I said, ‘He’s talking about becoming a deacon for this archdiocese.’,” Mary Lou recalled in her recorded interview with a detective investigating Wheeler. “‘And if you all make him a deacon and he ends up abusing any child, and now that you’ve heard my story – this is like a warning. Then, it’s on you.’”

Hannan died in 2011. Swiler died in 2016.

Church law required them to record the complaint. But years later, Aymond would insist that a complaint was never made.

LOSING FAITH PART 3

And in June 2018, Aymond ordained Wheeler a deacon.

Mary Lou told police she confronted Aymond about it, remarking: “I said, ‘There should be a record. And, archbishop, if there isn’t a record, here’s where you’re going to be in trouble.’”

The police interviews and public records also reveal that Aymond ordained Wheeler even after confronting him about his unethical business practices.

Public tax records show Aymond appointed Wheeler in 2012 or 2013 to the nonprofit board that ran the church's health system, Chateau de Notre Dame, later known as Notre Dame Health System.

Aymond told police that Wheeler used his position on the board to try to give his law firm work with the health system. At one point, Wheeler voted to approve work for the firm on a refinancing loan for two nursing homes, a source with knowledge of the board’s activities told WWL-TV.

Aymond later told Jefferson Parish Sheriff's detectives he knew Wheeler was involved in improper business activity but it wasn’t enough to remove him from the deacon training program.

“He would get on these boards and then he would want to do the legal work. Well, that's a conflict of interest,” Aymond said to detectives. “And I said, ‘VM, I hear all these things about you. At what point do we just say you're not capable of representing us?’”

Aymond told detectives he kicked Wheeler off the health system board. Public records show that happened in October 2016.

Less than two years later, Aymond ordained Wheeler a deacon at St. Francis Xavier Church.

LOSING FAITH PART 4

'Huge part of the problem'

Furthermore, when Mac later went back to meet with Aymond to fully disclose Wheeler’s abuse, he was supposed to remain anonymous to people outside that room.

Soon, though, Young started hearing from some of the powerful friends he had made in politics. The former mayor of the New Orleans suburb Harahan, defense attorney Vinny Mosca, called Young with legal advice.

“It would probably be in the best interests of the family to resolve it on a civil basis as opposed to a criminal basis,” Mosca – who has since died – said, according to what Young told investigators.

Then, when Young called prominent local businessman and longtime political supporter Frank Stewart to wish him a happy birthday, he got an earful about Mac’s allegations of abuse.

“He said, ‘I’d like to talk to you – I can’t talk to you right now, but I’m real disappointed about this Wheeler thing’,” Young recalled. Young says he replied: “Frank, that’s my son. I mean, what do you want me to say?”

Young added: “Apparently, he had been shown some things. Now, what they were, I don’t know.”

Another local businessman, Danny Kingston, also reached out. Young said Kingston’s aim was: “Just seeing if there’s anything he could do to help – if there’s any way to resolve this thing on a civil basis in terms of money, that type of thing. No figures discussed.”

Kingston declined comment. Stewart didn’t respond to messages.

In February 2021, months into the law enforcement investigation of Wheeler, church benefactor Louie Roussel called Mac’s lawyer, Richard Trahant. Mac said he understood that Roussel, an attorney and the former owner of New Orleans’s horse racing track, offered up to $400,000 “to make it go away.”

When Roussel called back during a follow-up conversation that was recorded, Trahant said: “It seems like Mr. Wheeler was offering money to have McCall stop cooperating with the police. And that bothered me. And I think it bothered you.”

Roussel said: “It bothered me tremendously. I didn’t sleep last night. You know, I don’t want to be involved with it.”

In his phone call with Trahant, Roussel acknowledges he had already talked with Aymond about the case against Wheeler.

“I called the archbishop and said, 'What the problem is here with Mr. Wheeler?'” Roussel recounted. “He said they had received a complaint of some improper behavior and that was it.”

Roussel has since denied that the payment was offered to cut off McCall’s cooperation with law enforcement, which would be illegal. He has said it was an offer in his capacity as a lawyer for Kingston, who was taking on an interest in Wheeler's mansion, to settle a civil lawsuit before it was filed.

For his part, Aymond provided a statement to WWL and the Guardian denying he ever revealed anything about Mac to anyone.

“I categorically deny revealing (Mac)‘s identity to anyone and have never and will never discuss the identity of an abuse survivor with any third party.”

One more twist awaited Mac before everything was resolved. Someone from Wheeler’s defense team at one point dropped off a packet on the doorstep of Trahant’s office containing confidential medical records. Those records were created during a 2010 stint that Mac had in a drug addiction rehabilitation program.

Somehow, Wheeler had obtained them, and now he was circulating them without having obtained a privacy waiver.

They were “definitely using privileged information … to try to keep me quiet,” Mac recently said. “Intimidation.”

But Mac pressed his case with his parents at his side. In December 2022, Wheeler pleaded guilty, was sentenced to probation and was required to register as a sex offender.

The sex offender registration infuriated Wheeler, and he abruptly backed out of an agreement of more than $1m agreement to settle the civil lawsuit Mac filed against him.

Wheeler, however, died in April. And in September, because the archdiocese’s bankruptcy filing didn’t shield Wheeler, his estate paid out Mac’s settlement, which is believed to be one of the largest involving abuse by a Catholic clergyman serving the New Orleans area.

Mac, who now dedicates himself to running a physical and mental health fitness program for schoolchildren, believes Wheeler’s addition to the credibly accused clergy list was the last piece missing from what he regards as total vindication for himself. Yet he is appalled at everything he had to go through to reach this juncture.

“It’s hard enough for the general population to accept this is happening,” Mac said, alluding to the skepticism that meets many clergy abuse survivors when they come forward. “And then you have these elite people stepping in to cover up, to pay off people. It’s not right. It’s illegal and it’s a huge part of the problem.”