Losing Faith: How a monstrous New Orleans deacon preyed on victims and avoided justice for decades

A four-part investigative piece focusing on the criminal cases against the late Catholic deacon George Brignac and 27 of his victims.

WWL-TV

A Monster in our Midst The Story of George Brignac

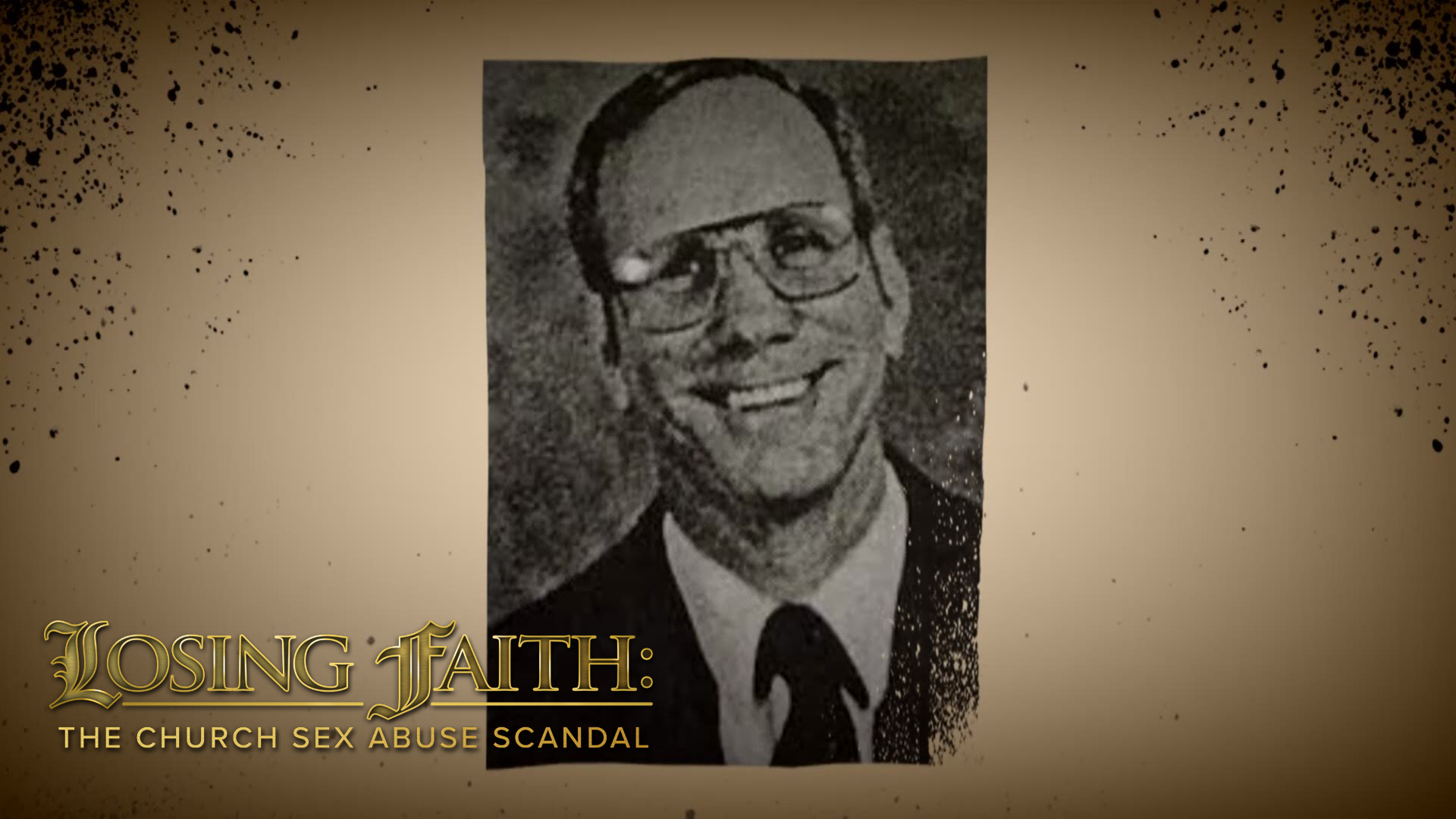

It was 1953, and George Brignac was fresh out of high school when he joined the regional chapter of the Christian Brothers.

He spent seven years with the Catholic order, which founded four well-known local schools: St. Paul’s in Covington, De La Salle and Christian Brothers in New Orleans, and Archbishop Rummel in Metairie. But, by 1960, the order had expelled him.

Brignac told some people it was for “reasons of health.” Another time, his superior in the order said Brignac found “obedience difficult.”

Years later, his twin, a priest named Horace L. “H.L.” Brignac, revealed the truth in a statement to police: George Brignac had been “too friendly with boys.”

Archbishop Phillip Hannan either didn’t know that or didn’t care when, in 1976, he accepted George Brignac into the clergy as a deacon. In the Catholic church, deacons rank below priests but are still considered members of the clergy.

An archdiocesan bureaucrat, the Rev. Edward Boudreaux, had judged Brignac “an excellent candidate” for the diaconate, one “most faithful to his preparation” for the role.

The role he would play was monster, the Orleans Parish district attorney’s recently released file on Brignac makes painfully clear.

The file contains more than 10,000 pages of internal archdiocesan memos, legal communications between the church’s and victims’ lawyers, and police reports, all gathered by prosecutors as they prepared to bring Brignac to trial. They believe that, by the time of his 1976 ordination, he had already molested at least 11 children.

He would go on to terrorize at least 15 more, inflicting abuse that ranged from fondling to violent anal rape -- acts that led to three arrests and an acquittal -- before the church in 1988 removed him from ministry. And those are just the known cases.

Brignac’s involvement with the church should inarguably have ended there. But it didn’t -- and he didn’t even have to leave town to start anew. A local Catholic community service group claiming it had no idea of Brignac’s past welcomed him as a volunteer, again putting him in a position of trust with access to children. That mistake was later compounded. Though he knew Brignac was a child molester, the pastor of a Metairie church in 2009 invited the fallen deacon to begin reading Scripture as a lector at Masses, an arrangement that wouldn’t end until it was exposed in the newspaper nine years later.

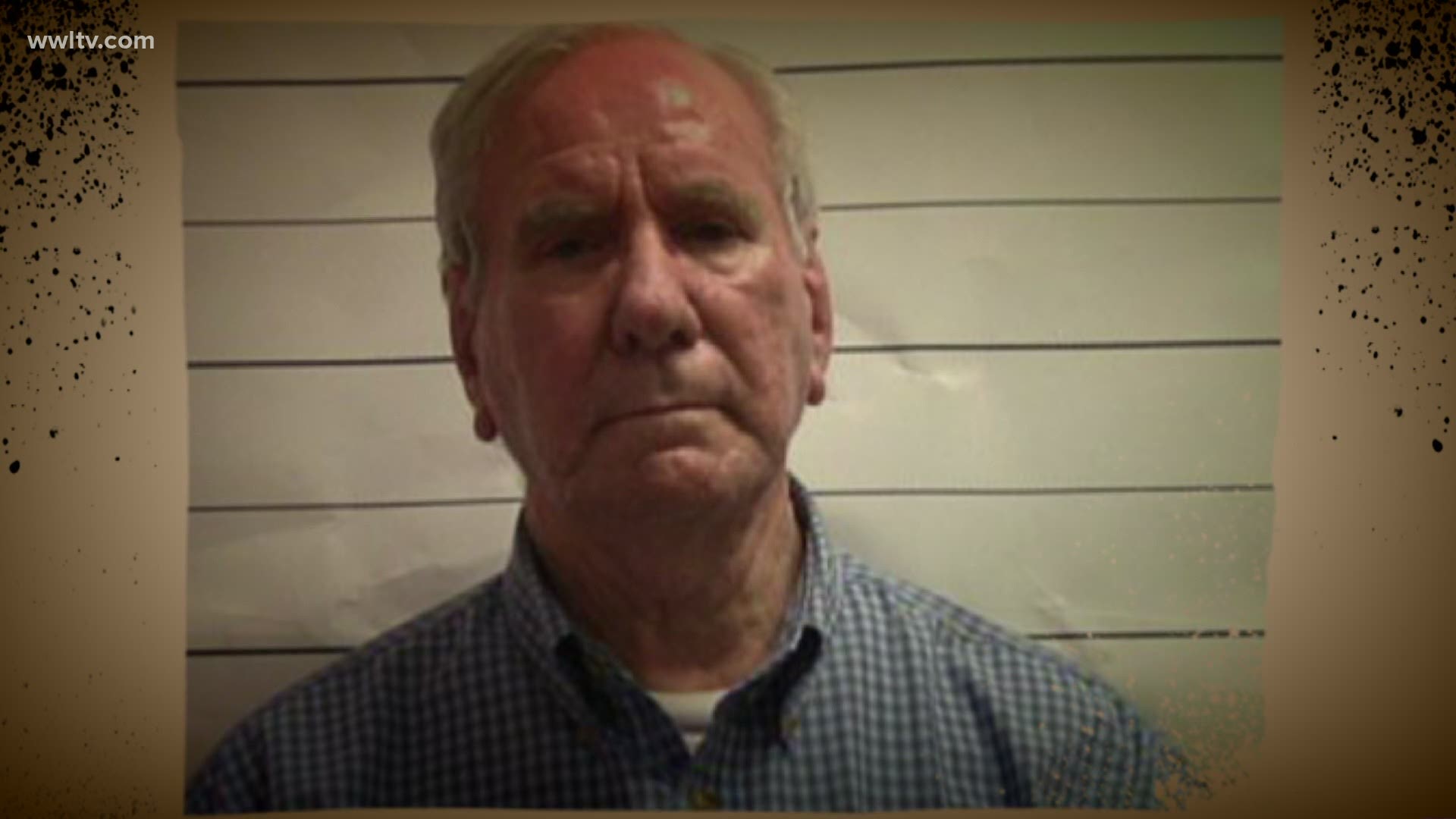

Once news reports exposed the church’s continued association with Brignac, the archdiocese paid upwards of $3 million in the span of a year to more than a dozen victims who came forward with claims against Brignac. New Orleans police in September 2019 arrested him a fourth time, in connection with child rape allegations from his time as a deacon, and then District Attorney Leon Cannizzaro’s office charged him with first-degree rape, though he died this summer awaiting trial.

It is the file in that case that recently became public, because of Brignac’s death. The arc traced by Brignac, one of the most incorrigible pedophiles to work in the New Orleans clergy, makes plain why the clerical abuse crisis has been so searing -- and so enduring.

The documents show that long before the Catholic Church faced a painful reckoning in 2002 over its handling of abusive priests, Brignac grievously harmed dozens of local children. And despite being caught, repeatedly, the only real price he paid was expulsion from the clergy -- a penalty he believed, until his death, was unfair to him.

The case file also shows how, despite promises to do better, the church gave in to its historic tendency toward secrecy.

Catholic officials never exposed Brignac as the chronic abuser they knew he was, allowing him to worm his way back into a place of trust -- something that would never have happened had the church been more forthcoming. Their reasons for keeping his crimes hidden are easy enough to understand: Acknowledging he was a serial predator would unleash a tsunami of new, expensive claims from victims. And, more broadly, they would likely contribute to a broader loss of trust from those who deplore the worldwide church’s handling of clerical molesters.

Yet in the long run, the church’s failures with Brignac likely exacerbated the inevitable toll. Now, in addition to the financial and emotional fallout from Brignac’s crimes, church officials must deal with anger over their failure to live up to the promises they and Catholic leaders all over the world made in 2002. Among those promises: that the church would take extreme measures to protect children; to always tell the truth; to demonstrate complete transparency.

But a program that proffered those reforms to rebuild trust knowingly let Brignac slip back into the orbit of the church -- and children. Around the time he was invited to read at Mass, Brignac enrolled in the archdiocese’s “safe environment” program, which trains church personnel to prevent child molestation and, should that fail, report it.

Brignac didn’t hide his sordid past. He wrote that he had been arrested, fired from at least one job, and even prosecuted for child abuse. Roughly two decades earlier, in a letter to New Orleans’ then-Archbishop Phillip Hannan, Brignac had admitted, “I realize that for the good of the church, and for my own personal good, I must not be allowed to be put in a position of authority or supervision of or work with young boys in the future.”

Yet Brignac was allowed to complete the training, just two months into Archbishop Gregory Aymond’s tenure. And a priest whom Brignac knew soon extended an invitation to serve as a Mass lector at St. Mary Magdalen.

The priest who vouched for Brignac in writing, the Rev. Robert Massett, would later tell police that the disgraced deacon quickly took an interest in an altar boy in a wheelchair, trying -- but failing -- to persuade his mother to let the child come over to Brignac’s home. Brignac would later also teach children about a springtime celebration marking the Virgin Mary’s reported 1917 apparition in Portugal, and picking out the kids’ costumes for a centennial feast.

Aymond this week said he had no idea about Brignac’s involvement at St. Mary Magdalen until the summer of 2018, nine years into his tenure. The archbishop called Massett’s invitation to Brignac “an error without justification,” and archdiocesan officials said a document Massett signed approving Brignac’s role never made it to the archdiocese. They insisted they have since fortified the measures that faltered.

Brignac’s return was hardly the only broken pledge. When negotiating an out-of-court settlement with one of Brignac’s victims in 2018, the archdiocese’s general counsel -- Wendy Vitter, now a federal judge and the wife of a former U.S. senator -- demanded bluntly in an email that the $100,000 payment amount remain confidential.

U.S. bishops' transparency policies since 2002 have prohibited imposing confidentiality on abuse victims. Victims’ advocates say demanding any aspect of a settlement agreement violates those policies. Archdiocesan officials counter that they are permitted to try and keep the size of a settlement confidential.

“I feel like their goal in all of this is to simply sweep it under the rug and try to save face with their followers and also to try to save their money,” said the victim from the criminal case brought against Brignac last year. “They have known who and what George Brignac was for quite a long time.”

‘Positive recommendation’

When he examined Brignac’s application to become a Catholic deacon in 1974, the Rev. John Favalora, the head of the program, was clearly worried.

Brignac had attended St. Paul’s in Covington and De La Salle in New Orleans, graduating from the latter in 1953 and immediately joining the religious order which founded both high schools: the Christian Brothers. But by 1960 he had been kicked out. He spent the next few years teaching students from 5th to 8th grades at various local Catholic schools, including at St. Matthew the Apostle in River Ridge, where he was also a prefect of discipline.

Nine years into his stint at St. Matthew, Brignac was having a hard time explaining his expulsion from the Christian Brothers.

One record of a conversation between Brignac and an archdiocesan leader says Brignac claimed he was dismissed for vaguely explained “reasons of health.”

“I think more information is needed,” the interviewee wrote.

Favalora, who later became the Archbishop of Miami, sent a letter to a Christian Brothers official, asking about Brignac. “This information will be kept in confidence,” Favalora wrote.

It isn’t clear what the response was. But a handwritten scribble on Favalora’s letter mentions a “positive recommendation” from the order.

Brignac pleaded to be let into the diaconate. The Catholic Church allows married men to become deacons, but they may not marry after ordination. Brignac had never married.

“I fully understand the church’s law of celibacy,” Brignac wrote to Hannan on April 4, 1976. “And I firmly resolve that, with God’s help, I will fully keep it and completely observe it until death.”

The following month, he was ordained and assigned to Our Lady of the Rosary in the 3300 block of Esplanade Avenue.

In a self-evaluation at the end of his first year in ministry, he was asked his favorite aspects of ministry. He replied: “Working with youth.”

‘Victim of his own celibacy’

Brignac continued to teach at St. Matthew. In 1977, his second year as a deacon, three students accused him of sitting them on his lap, shoving his hand down the boys’ pants, and fondling their genitals.

John Anderson, then 11, recalls how Brignac would inflict the abuse in a classroom where other students were present, using two desks to hide what his hands were doing.

“I was scared to death,” Anderson recalled. “I didn’t know what to do.”

Anderson said a boy who saw what Brignac was doing told Anderson’s mom about it during a ride home from school. Anderson said he threw up. His mother initially froze in shock, but then she reported Brignac to the Jefferson Parish Sheriff’s Office.

Deputies arrested the newly minted deacon, and prosecutors charged him with three counts of molesting a juvenile.

Brignac, then 43, pleaded not guilty. His attorney, Arthur Kingsmill, theorized that the accusations stemmed from the church’s insistence that clergymen forego sex.

“George is a victim of his own celibacy and society’s willingness to jump to the conclusion that a middle-aged celibate must not be sexually straight,” Kingsmill wrote in a letter years later. “This tendency … (has) crucified a man who loves children in the purest of ways.”

Ultimately, Brignac was found not guilty at a judge trial in 1978.

That same year, he was allowed to move from St. Matthew’s faculty to the one at a familiar place: Our Lady of the Rosary, where as a deacon he had served his entire career.

Familiar allegations

He didn’t lose access to kids. In fact, he became co-director of the altar boy program at Our Lady of the Rosary, just down the road from Bayou St. John.

In June 1980, familiar allegations surfaced.

An 11-year-old boy alleged that, at lunch, Brignac had tickled his chest, fondled his penis and asked the child for a kiss.

Within days, New Orleans police booked Brignac with molestation of a juvenile. But there’s no indication prosecutors ever filed charges. A church document from 2001 doesn’t even mention the arrest.

After the case against him foundered, Brignac took a job at neighboring Cabrini High School, an all-girls school, and taught mathematics and religion.

He and other deacons received expanded responsibilities in 1985, most notably with regards to weddings. Hannan’s letter explaining the new duties to Brignac thanked him for his “years of dedicated service to the Archdiocese.”

“It is through your gift of yourself that we are able to reach out to so many with the love of Christ,” Hannan’s missive said.

Brignac didn’t enjoy the new privileges for long.

In 1987, a 7-year-old boy reported that, during a Christmas party at Our Lady of the Rosary, he was pulled aside by Brignac, who paid the boy compliments, placed an envelope with money in the student’s front pocket, and began groping his genitals. The boy said it was not the first time.

In a letter many years later, a civil attorney representing the victim alleged the child’s mother had immediately called Our Lady of the Rosary. The attorney claimed one of Brignac’s fellow clergymen at the church said perhaps the boy “had taken the events ‘the wrong way.’”

The boy’s family called the police. Brignac, yet again, was booked with molestation. And this time, in 1988, then-Orleans Parish District Attorney Harry Connick’s office filed charges.

But when the boy arrived at Criminal District Court to testify, he was rattled by the scene.

At least 50 priests sat in the rows behind Brignac and his attorney, Vincent LoCoco, who was also the board president of Our Lady of the Rosary’s school.

The victim’s family knew many of the priests. Facing them, the child lost his nerve, the letter said.

To spare the child from the ordeal, the family agreed to let Connick’s office drop the charges.

Hannan was elated at the news. He wrote a letter thanking LoCoco for “the good news that the District Attorney’s Office … has dismissed the case against Deacon George Brignac.”

“I am deeply grateful to you,” Hannan wrote to LoCoco, “for your excellent work in this case and your wonderful support of Deacon Brignac.”

This time, Brignac at least faced some consequences.

He “signed an agreement that he would have no contact with young boys for a period of years,” an internal church memo written many years later revealed. He also agreed to undergo at least 17 psychotherapy sessions aimed at helping him achieve “appropriateness of … behavior in his work and in his relationships.”

The Archdiocese of New Orleans, meanwhile, indefinitely suspended Brignac from working as a deacon. And Cabrini fired him, ending a roughly 32-year career in teaching.

Two priests at Our Lady of the Rosary, Edward Boudreaux and Lanaux Rareshide, cried foul in a letter to Hannan.

The letter alleged that the 7-year-old accuser’s own family, along with an attorney, a psychiatrist and a police detective, all said “they did not think the child had been molested.”

“It is judged that Feldner did not do anything wrong,” their letter said, referring to Brignac by his middle name.

Boudreaux and Rareshide also argued that it wasn’t that dangerous to keep Brignac at Our Lady of the Rosary. “Only 61 children” attended the school. About half that number were enrolled in a program that prepared children to receive the sacraments.

“Our Lady of the Rosary Parish has a largely older population,” the monsignors wrote. “Feldner can be most helpful to this (church) through care for the elderly and participation in (church) adult groups.”

Brignac also beseeched Hannan for another chance.

He admitted he gave the 7-year-old money “to spread joy” but denied molesting him. Nonetheless, he conceded it was in the best interests of both the archdiocese and himself to “not be … put in a position of authority or supervision of or work with young boys in the future.”

Brignac added: “If I am guilty of anything it is that I am a caring, loving and affectionate person and that this conduct may be misinterpreted by some people. … I know that I am a person who is outwardly affectionate with young persons but I did not treat anyone in an immoral way nor seek sexual gratification from any child.”

To Brignac, the thought of starting over professionally at 53 was overwhelming. He didn’t understand why he couldn’t continue serving as long as he avoided contact with children.

“I am willing,” he wrote, “to submit to that restriction if that be the condition on which I can return to the ministry I have served well for twelve years.”

In his letter to LoCoco, an outgoing Hannan promised to discuss the prospect of reinstating Brignac with his successor, Archbishop Francis Schulte.

Schulte shot Brignac down, as gently as possible.

“Please be assured that I am aware of your many years of faithful and dedicated service to the Archdiocese of New Orleans,” Schulte wrote to Brignac in 1989. “Much as I would wish otherwise, I cannot offer any encouragement to you for the restoration of your (deacon’s) faculties at the present time.”

However, Schulte added, “I will certainly remember you in prayer, asking the Lord to sustain you during this special time of difficulty.”

The letter makes no reference to the five boys Brignac had been accused of molesting by then or the suspended deacon’s three arrests.

It seemed that New Orleans’ archdiocese had at last disassociated with Brignac. Yet, despite his profile as an inveterate child predator, he soon carved out roles at other local Catholic institutions.

Each would bring him in close proximity to children.

The Monster Returns Despite his predatory past, George Brignac was welcomed back to Catholic institutions.

Anyone else in George Brignac’s shoes -- saddled with the disgrace that accompanies his name -- might have gotten the hell out of Dodge and tried to reinvent himself, to outrun the shame.

Over the 12 years he served as a deacon at Our Lady of the Rosary Church, beginning in 1976, Brignac had been accused of molesting at least five boys and was arrested by authorities at least three times.

Brignac, who was also a schoolteacher, was never convicted. But he was forced to sign an agreement, under duress, to stay away from children. And, though some fellow priests objected, the Archdiocese of New Orleans suspended him from ministry in 1988.

Just 53 at the time, Brignac fretted about his next move. It isn’t entirely clear what he did over the next decade. But he had no intention of giving up his involvement with the Catholic Church, which would ultimately open its doors again to him in a way that allowed him access to children, according to thousands of pages of documents in Orleans Parish prosecutors’ files that were released after Brignac’s death earlier this year.

The local Knights of Columbus, a Catholic community service organization, accepted Brignac in 1998, just 10 years after his suspension.

In a statement this week, a Knights spokesperson said the organization -- which is separate from the archdiocese -- wasn’t “aware of Mr. Brignac’s history” at the time. The spokesperson said the Knights don’t run background checks on new applicants because the organization isn’t focused on youth services.

Over the next 20 years, Brignac would hold a range of several different volunteer titles there, including that of “chaplain” and “faithful friar,” which are typically reserved for priests, records say.

Brignac’s association with the Knights survived a 2002 Boston Globe investigation that showed the worldwide church had covered up thousands of cases involving clergymen who had molested children.

The scandal did cause Brignac some grief. It prompted then-New Orleans Archbishop Alfred Hughes to convert Brignac’s indefinite suspension from the clergy into a permanent one, at the suggestion of a board reviewing abuse cases.

In a 2002 letter, Hughes recommended that Brignac ask the Vatican to remove him from the clergy through a process called “laicization.”

Brignac wasn’t interested. He complained in a letter that Hughes had acted “without any consultation with me.”

Brignac said he had sought counsel from people he trusted and respected.

“I have been advised and I agree that I should do nothing about my status that would imply even in the slightest way that there is any credence to the allegation against me, which is false,” Brignac said. “My position is so obviously correct that I am confident you would concur in it.”

There is no indication Hughes pursued laicization any further. He didn’t immediately respond to a message seeking comment.

‘Innocent until proven guilty’

Brignac was continuing to serve as a Knights of Columbus officer when, in 2009, he encountered the Rev. Robert Massett, the pastor of Metairie’s St. Mary Magdalen Church.

Soon, the pastor was recommending Brignac to read Scripture at Masses at St. Mary Magdalen, where the Knights have a chapter, the pastor told an investigator many years later.

Massett, who retired in 2016, said he knew at the time that Brignac had been arrested multiple times on molestation allegations, and that that record had cost Brignac his career in teaching as well as his Roman collar.

Inexplicably, about the time of Massett’s invitation in late August 2009, two months into current Archbishop Gregory Aymond’s stint in New Orleans, Brignac was allowed to complete an archdiocesan course aimed at ensuring the church doesn’t give child molesters like him access to kids. The course, developed in the wake of the 2002 scandal, trains church personnel to prevent and report child abuse.

Despite knowing about Brignac’s abhorrent past, Massett signed the ex-deacon’s paperwork. Since then, additional safeguards have been added where the program’s coordinator is automatically alerted about any concerns on paperwork, the archdiocese said.

But those didn’t exist at the time, and Brignac sailed on through the course.

In a recent interview, Massett said he believed Brignac was worthy of a second chance and should be considered “innocent until proven guilty.” Massett claimed he had been told that one of Brignac’s accusers had recanted. But that accuser has never recanted.

In any event, Massett said, the church was not going to let the disgraced deacon work with children.

“As long as he is not involved with children, what’s wrong with a man being involved with the church?” Massett said.

Massett ultimately learned that restriction hardly deterred Brignac.

Massett later told District Attorney Leon Cannizzaro’s office that several parents had approached him to warn him that Brignac was cozying up to a child in a wheelchair. In a recent interview, Massett downplayed the seriousness of Brignac’s advances, saying he only saw Brignac talking to the boy once, and that a parent put a stop to it.

In a recent interview, the boy’s mother, who asked to not be identified, told reporters a much more chilling story. She said Brignac met her son while the boy took classes, sponsored by the Knights, meant to prepare children to receive the sacraments.

Throughout her son’s four years as an altar boy, starting in about 2011, Brignac would talk to him after Mass, she said. The mom recalled Brignac often told her that her son was welcome to come over to his home anytime.

He would also send the boy birthday and Christmas cards, and little gifts, like magnets and other knickknacks, she said.

But she never allowed Brignac to be alone with her son.

“We didn’t even really know him,” she said. “We just knew him from the 10 minutes we would spend with him after church.”

She described herself as equally relieved and disturbed when the full truth about Brignac came out. She said she strongly suspects Brignac was grooming her son to become his next victim, perhaps sensing the boy’s physical disability might make him an easier target.

“I feel like if we hadn’t had complete supervision of (the boy), that wouldn’t have gone well,” the mother said. “That would’ve been bad.”

Coming forward

That wasn’t Brignac’s only recent close encounter with children that was facilitated by the church.

In 2017, in his role with the Knights of Columbus, Brignac spoke to a group of kids at St. Mary Magdalen about a century-old miracle in Portugal. For a feast and procession commemorating the apparition of the Virgin Mary, Brignac also suggested having three students wear Portuguese “period dress,” emails show.

Both the school and the Knights were effusive after the event.

“George Brignac has spent a great deal of effort explaining to our members the various facts of the Fatima appearances,” the leader of the Knights chapter wrote the school principal. “To do so to the children today was very special for him. And our entire (chapter) as well!”

The principal wrote back: “You are so welcome! Thank you for thinking to include the school. Today was very touching!”

Less than a year after Brignac’s Fatima triumph, two unrelated major developments exposed his problematic ongoing association with the Catholic Church.

First, the Diocese of Erie, Pennsylvania, in April 2018 published a list of 34 priests and 17 laypeople faced with credible accusations of child sexual abuse, ahead of a state grand jury report detailing hundreds of other Pennsylvania cases that had previously been concealed.

Meanwhile, a Slidell man filed a lawsuit alleging that he had been anally raped by Brignac over a five-year period beginning in 1978, when the plaintiff was an altar boy at Our Lady of the Rosary.

The archdiocese and the plaintiff, represented by attorney Roger Stetter, soon agreed to settle the case out of court for $550,000 -- a large sum for a decades-old abuse claim.

Initially, Stetter’s client had asked that the size of the payment remain confidential. But after the agreement was struck, the plaintiff dropped that request.

He and Stetter spoke to the local news media about the settlement. And it changed everything.

Brignac by then was about to turn 85. At last, his story was coming to a close.

End of a Monster Archdiocese of New Orleans pushed confidential settlements with George Brignac's victims

The email to the Archdiocese of New Orleans came in on a Friday in November 2018.

A week earlier, New Orleans Archbishop Gregory Aymond had published a list of clergymen credibly accused of child molestation -- a first-ever effort by the leadership in this traditionally Catholic city to fully come clean about the depth of a scandal that blew up in 2002 and had begun to simmer again in the summer of 2018.

The scandal’s recent flareup owed mostly to the first name on the list, which was organized alphabetically: George Brignac. That name jumped out at one man, and it prompted him to write the email.

Brignac had been arrested three times in the 1970s and 80s on molestation charges, before the archdiocese permanently suspended him from his duties as a deacon. But despite his extensive rap sheet and his removal from the clergy, Brignac had gone on to spend another 20 years volunteering with a Catholic community service organization, and -- with the blessing of two different pastors -- he had been reading at Masses at St. Mary Magdalen in Metairie. Both roles brought the former Catholic school teacher into proximity with children and gave him an imprimatur of trust, despite his own written admission, for his own good, and theirs, he should not be allowed to work around minors.

That arrangement had largely escaped public notice until the summer of 2018. That’s when a local man announced in a newspaper story that he had received $550,000 from the archdiocese after he explained he was raped as a child by Brignac decades earlier.

Aymond has said he was unaware subordinates of his at the local parish level had brought Brignac back into a low-profile role, and his hope was the release of the list of abusive priests would prevent something like that from recurring. But the list -- along with news of the $550,000 settlement -- brought on a torrent of fresh claims, including the one from the man who emailed the archdiocese on Nov. 9, 2018.

He was among more than a dozen other men who came forward with similar stories about Brignac. His ensuing experience, detailed in thousands of prosecutors’ files released after Brignac’s death earlier this year, offers a glimpse into how acrimonious the negotiations can get, even as church officials say their primary goal is to help victims heal.

The man, who has never publicly identified himself, wrote that he was in sixth grade in 1978 at Our Lady of the Rosary’s school when Brignac first “groomed and methodically” molested him, groping his genitals, abuse that went on for two years. He said he first came forward in 2003, after the exposure of covered-up clerical abuse cases in Boston shocked the nation. But, the high-ranking priest who spoke with him -- Monsignor Ray Hebert -- dropped the inquiry after Brignac denied “strongly that he has ever sexually abused or molested a child.”

Brignac “believes that the church has been unfair to him by denying him the right to be a deacon or a teacher,” Hebert wrote the man. “He is hurting.”

Now, 15 years later, the victim spoke with a different church official. This one was more sympathetic. “I do believe you and want to help you resolve this,” said Stephen Synan, a religious brother and the archdiocese’s victims assistance coordinator.

Synan’s proposed solution: a $55,000 payment to help the man “move forward.”

The victim -- who wanted at least $350,000 for his lifelong anger and depression -- wasn’t having it. “To say I am disappointed in the offer is an understatement,” said the man, who turned to a civil attorney.

The archdiocese’s general counsel at the time, Wendy Vitter, quickly warned him that if he overplayed his hand, he could come away with nothing.

In a Dec. 21, 2018, email to the man’s attorney, Steven Babcock, Vitter said Louisiana law is clear that the claimant had one year from when he was last abused to begin pursuing damages. Legally, it doesn’t matter if he was a minor, Vitter said.

The plaintiff said the one-year period shouldn’t apply because it wasn’t until 2018 that Brignac was unmasked as a molester. But Vitter, who last year was confirmed as a federal judge by the U.S. Senate, warned that was going to be a tough argument to win. Its weakness, she added, was compounded by the victim’s decision to come forward once earlier, in 2003.

The fact that the church brushed him off back then was of no consequence, from Vitter’s perspective.

“The Archdiocese submits … a court will dismiss (the victim’s) lawsuit as untimely,” Vitter wrote. “Nothing that the Archdiocese has said or done has revived his untimely claims.”

But, Vitter added, the victim’s “anger towards the church is evident.” She said, “We try to care for people. That is part of our ministry.” So she extended a non-negotiable, $100,000 settlement offer “out of pastoral care and concern.”

She had one more condition.

“The amount of the settlement will be confidential,” her email said. “That must be part of any agreement.”

Transparency provisions that U.S. bishops adopted after 2002 state plainly that dioceses “are not to enter into settlements which bind the parties to confidentiality unless the victim/survivor requests confidentiality.” In a statement this week, the archdiocese argued that “the decision to request confidentiality on the dollar amounts of settlements does not violate” those provisions.

Vitter didn’t respond to a message seeking comment.

Babcock’s client ultimately accepted the offer of $100,000. Vitter replied that the archdiocese would work to “get this done very quickly” and sincerely hoped the victim “finds some peace in the future.”

Emotional Wreckage

Such negotiations played out between the archdiocese and at least 17 men who settled claims against Brignac with the church between April 2013 and May 2019.

All but two of those agreements came toward the end of that period, as word of the $550,000 settlement made in early 2018 spread like wildfire. That agreement was the largest one, with the rest ranging from $25,000 to $495,000. One claim dating back to 2002 and settled in 2013 was worth $88,500.

In total, the settlements cost just over $3 million.

The victims were children from four different decades, born from the mid-1950s to the early 1980s. Several said they were abused by Brignac, a longtime teacher in local Catholic schools, before his 1976 ordination as a deacon but after his 1960 dismissal from the Christian Brothers religious order.” Many others said they were abused during Brignac’s 12-year run as a deacon.

They recalled suffering a wide range of abuse at his hands, from inappropriate touching and genital groping to violent anal rape. At least a couple of them had reported Brignac to authorities, who had arrested him three times, though none of those bookings led to a conviction. Most came forward only recently.

Taken together, those 17 cases began to provide a clearer picture of the scale of emotional wreckage Brignac wrought. But the list is by no means complete.

For example, one woman came forward during this time and reported that while she took a make-up math test as a sophomore in 1984 at the all-girls high school Cabrini, Brignac -- in his first of four years there -- groped her breast while breathing heavily and licking his lips. It is not clear whether she pursued a settlement; so far she appears to be Brignac’s only known female accuser.

Another alleged victim not included in this toll is a man who filed a highly publicized lawsuit against Brignac that turned up emails between archdiocesan officials and members of the New Orleans Saints football team’s front office as the church sought to manage the fallout of the ongoing clerical molestation scandal.

That lawsuit, along with dozens of other similar ones alleging clergy abuse, was indefinitely put on hold after the archdiocese filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in May.

Prosecutors’ files contain written exchanges between the archdiocese’s lawyers and attorneys for at least some of the claimants who settled. Without fail, lawyers representing the church or its insurers took a hard line, arguing that plaintiffs had waited too long, and that they would be lucky to get anything.

One such memo argued that the man who ultimately received the largest settlement should have filed his claim within a year of the moment -- decades earlier -- that his mother spotted a hickey on his neck left by Brignac. The man and his attorney, Roger Stetter, countered that the victim had blocked memories of his assaults until his mother ran into Brignac in 2017, and that the one-year clock should start then.

That argument, the church’s lawyers contended, was “irrelevant.”

An archdiocesan spokesperson this week said positions taken by the church’s attorneys don’t reflect the beliefs of Aymond or other clerical leaders. The spokesperson said Aymond’s willingness to release the list of clerical abusers and update it as new information comes forth shows he listens to victims.

The flood of victims who came forward in 2018 and 2019 weren’t the only ones who took note of Brignac’s story. New Orleans police and prosecutors did as well.

Charged again

The road to Brignac’s fourth -- and final -- child molestation arrest started in August 2018, when the recipient of the $550,000 settlement met with New Orleans police.

He recounted how from 1978 to 1982 -- when he was between the ages of 7 and 11, serving as an altar boy at Our Lady of the Rosary -- Brignac forced him to engage in oral sex, masturbated in front of him and eventually began raping him.

The victim -- now a National Guard veteran and medical professional -- bolstered his account with handwritten notes from Brignac reading, “I love you,” “I’ll miss you,” and “can’t wait to see you again.”

Police decided they had heard and seen enough to prepare first-degree rape charges against Brignac. The charge has no statute of limitations.

The ensuing probe, conducted jointly by police and Orleans Parish District Attorney Leon Cannizzaro’s office, was ambitious. Documents obtained through a public records request show the DA’s investigators found at least one other man who reported being anally raped by Brignac.

That second man would be among the youngest of Brignac’s victims, saying that he was 3 or 4 when the serial molester preyed on him between 1983 and 1984 at Our Lady of the Rosary. In his statement to police, the victim said his mother was a volunteer in the church cafeteria. Brignac would approach him in the hallways, tease him about having been naughty and then pull him into the back of the church.

There, the victim later told a detective, Brignac would say that he needed to clean the boy because the child had soiled himself. Brignac would then rape him, warning it would feel like “a big mosquito” biting him in the rear, the victim said.

At least one person told police Brignac was innocent: his twin, Horace, nicknamed H.L.

H.L., who died in April, confirmed his brother knew the former altar boy now accusing him of rape, and acknowledged George may have touched his genitals. But H.L. insisted his brother would’ve stopped short of rape: He said George didn’t touch children “for immoral reasons because his brother was not looking for gratification,” according to an investigator’s notes.

Police decided otherwise, and they arrested George Brignac in September 2019. Three months later they indicted him on a charge of raping the altar boy. Cannizzaro said this week his prosecutors believed the altar boy’s case was the strongest one they had.

Brignac, who bonded out of jail after being charged, would face mandatory life imprisonment if convicted.

Though he pleaded not guilty and retained veteran attorney Martin Regan to defend him, a reckoning seemed to be building. Records suggest prosecutors also planned to charge Brignac with the rape of the cafeteria volunteer’s son. And they had identified at least 25 other men -- including the former cafeteria worker’s son -- who were prepared to testify that they, too, had been victimized by the deacon, though either statutes of limitation or a prior acquittal barred additional charges.

They included a combination of people who had settled civil cases or were working to do so; victims at the center of Brignac’s prior arrests; and other claimants who had not previously come forward. The testimony from such a phalanx of survivors would buttress the accounts given by the ex-altar boy.

The question was whether the ex-deacon, now 84 and enfeebled, would live long enough to hear it.

End of a monster

The chances for a trial in 2020 waned when the coronavirus pandemic shut down Criminal District Court starting in spring.

Brignac was in frail health, living at an Uptown nursing home while battling heart disease, high blood pressure, peripheral nerve damage and other medical conditions. He had also fallen and broken his back about the time he was charged.

As local spread of the coronavirus slowed in the summer, Criminal District Court Judge Karen Herman scheduled a preliminary hearing for July 9.

But on the morning of June 29, Brignac was short of breath. He went into cardiac arrest as paramedics rushed him to Touro Infirmary.

A doctor pronounced Brignac dead soon after his arrival, a coroner’s office report said.

He was 85.

The former altar boy who triggered Brignac’s final arrest said the news of his longtime tormentor's death set off conflicting emotions.

“I did want him to be acknowledged as a pedophile and the criminal and the monster that he was and that we know he was and many other people know he was,” the man said recently.

But he dreaded the thought of testifying and the intense news coverage it would likely generate. And, a part of him felt relief.

“I wouldn’t have to get up in front of a jury and relive all the horrible experiences that I’ve had to relive multiple times,” the man said.

Now, perhaps, he mused, he was ready to begin the process of moving on with the rest of his life.

But it wouldn’t be easy.

“Nothing can change what I went through,” he said.

In his will, Brignac wrote that he wanted six former students to serve as his pallbearers. He left some of them money. Others got things like a Rosary, a luxury watch, a nice pen and fancy cufflinks.

Teaching children, he said, was his life’s greatest privilege.

“The children who have come under my care for the 32 years I taught school have been my family and my joy,” Brignac wrote. “My only regret is that I was not a better role model to them and that most of them never really understood how much I loved them and wanted to share myself with them.

“I hope they have learned to love God and His Blessed Mother and that I haven’t caused them too much disappointment or harm.”

The Monster Hunters The defendant in their sights who got away.

For Leon Cannizzaro, preparing to leave office after 12 years as Orleans Parish district attorney, one defendant that was in his sights and got away is a particularly vexing one: the inveterate child molester and former Catholic deacon George Brignac.

Cannizzaro had more than two years left in his final term when the local archdiocese in November 2018 released the first version of a list of clerics who had been credibly accused of child molestation over the decades.

While district attorneys in other parishes -- and some of his predecessors in New Orleans -- have largely shied away from prosecuting pedophile clergy, Cannizzaro, a former Catholic altar boy, said his prosecutors scoured the list for potential criminal cases.

They secured charges against only one of the clergymen on the roster, which first had 57 names but has since grown to 73: Brignac, who was suspended from his duties as a deacon in 1988.

Cannizaro this week said that was because Brignac was the only person still alive in 2018 who had been credibly accused of anally raping a child in the city, a crime that carries no statute of limitations. The rest either offended outside of Cannizzaro’s jurisdiction or committed crimes with a shorter statute of limitations, such as fondling.

Engaging in oral sex with a child younger than 13 today is considered rape and would have no statute of limitation. But that wasn’t the case between the 1960s and early 1990s, when the bulk of the molestation claims at the heart of the list occurred.

“Basically, that activity (had) prescribed,” the term for what happens to a case after the statute of limitations expires, said Cannizzaro. “We could see in some of the victims that they talked about a gradual progressiveness of more familiarity and more intimacy, and many of those cases … did not rise to the level of … rape.”

Brignac, who died earlier this year at age 85, was among the most prolific abusers on the roster of molesting clergymen that Archbishop Gregory Aymond released two years ago.

At the time of the list’s publication, New Orleans-area authorities had arrested Brignac three times between 1977 and 1988.

In those cases, Brignac, a longtime school teacher at local Catholic schools, was accused of fondling a total of five boys. He was acquitted after one arrest in Jefferson Parish, and prosecutors in New Orleans dropped the other two cases without trying them in court.

The Archdiocese of New Orleans indefinitely suspended Brignac following the third arrest, and in 2002 it converted that suspension into a permanent ban. Yet despite his history of arrests, the Knights of Columbus -- a Catholic community service club -- allowed Brignac to become a member of a chapter at St. Mary Magdalen in Metairie. Two pastors there then allowed Brignac to serve as a reader at Mass beginning in 2009.

Media reports exposed that association in the summer of 2018, after a former altar boy who accused Brignac of raping him in the early 1980s publicly discussed a $550,000 settlement he received from the archdiocese.

The man’s story preceded the decision from Aymond to release the clergy abuse list, an effort to come clean about the scale of the lingering molestation scandal. Publicizing such a list would ensure nobody like Brignac could be mistakenly allowed again to participate in church services and clubs, the archbishop has said.

The list also prompted more than a dozen additional accusers of Brignac to come forward, and they in turn captured the attention of New Orleans police.

Police ultimately booked Brignac on a count of raping the ex-altar boy whom Brignac used to supervise at Our Lady of the Rosary Church near Bayou St. John. Cannizzaro’s office followed up with charges against Brignac, lining up at least 25 men who were prepared to testify that Brignac had preyed on them sexually as well. They included a combination of victims from the prior criminal cases as well as some who had received financial settlements.

But Brignac, who pleaded not guilty, died on June 29 while out on bail.

Cannizaro said Brignac’s death pained him because the emotional wreckage the ex-deacon had wrought on the witnesses in the case was palpable.

“We’re talking about grown men in their 50s who carried those events with them to this very day,” Cannizzaro said. “They were very honest in saying, ‘That has affected my life to this very moment. I’m going to die knowing what happened to me.’”

Cannizzaro said Aymond and his aides at the archdiocese cooperated fully in the investigation against Brignac, despite the wave of unflattering news coverage surrounding the charges against him.

“I think that’s important to know,” Cannizzaro said. “They did not do anything to try to stifle or stymie what we were doing in this office.”

Cannizzaro acknowledged his Catholic upbringing made the Brignac case unique. Not only was he a former altar boy, but like Brignac he is an alum of the Christian Brothers-founded De La Salle High School.

Nonetheless, Cannizzaro said deciding to press a case against Brignac was an easy call.

“I’m not going to quote the Bible, but I know (God) said something about, ‘Don’t hurt kids,’” Cannizzaro said.

Cannizzaro’s final day in office will be Jan. 11 after he opted against seeking re-election. He will be succeeded by Jason Williams, who won a runoff earlier this month.

Currently, one living New Orleans-area priest is facing prosecution for allegations of child molestation: the Rev. Patrick Wattigny. The St. Tammany Parish Sheriff’s Office arrested Wattigny in October on counts that he molested a teenage boy at least four times between 2013 and 2015.

The archdiocese indefinitely suspended Wattigny from public ministry, added him to the list of credibly accused clergy and is seeking to have him laicized, or removed from the clerical state.

Timeline This is a timeline on the pedophilia cases against the late Catholic deacon George BrignacSubtitle here

- Jan. 6, 1935: George Feldner Brignac is born.

- 1953: Brignac graduates from De La Salle High School, which was founded by the Christian Brothers. He joins the order soon after graduation.

- 1960: The Christian Brothers dismiss Brignac for reasons that aren’t immediately clear. Many years later, his twin brother -- the late Rev. Horace L. “H.L.” Brignac -- says George is kicked out for being “too friendly with boys.”

- 1964: Brignac begins teaching at St. Matthew the Apostle in River Ridge. He also serves as a prefect of discipline.

- 1976: The Archdiocese of New Orleans ordains Brignac as a deacon. He is assigned to Our Lady of the Rosary Church in the Bayou St. John neighborhood. Archdiocesan leaders either never learned the reason for Brignac’s dismissal from the Christian Brothers, accepted Brignac’s claim that it was “for reasons of health,” or didn’t care.

- 1977-78: Three boys at St. Matthew accuse Brignac of fondling them. Jefferson Parish authorities charge the deacon with three counts of molesting a juvenile. He pleads not guilty and wins an acquittal at a bench trial.

- 1978: Brignac is allowed to move from St. Matthew’s faculty to Our Lady of the Rosary, where he is still a deacon.

- 1980: A boy alleges that Brignac fondled the child’s penis, tickled his chest and asked for a kiss. New Orleans police again book him with molestation of a juvenile, but there’s no indication prosecutors ever filed charges. It’s unclear why.

- 1984: Brignac leaves Our Lady of the Rosary’s school but remains a deacon at the church there. He teaches at Cabrini High School for the next four years.

- 1988: New Orleans prosecutors charge Brignac with groping a boy at a 1987 Christmas party. When a large group of priests shows up in court in support of Brignac, the boy loses his nerve to testify. His family agrees to let prosecutors drop the case. Brignac undergoes psychotherapy and agrees to avoid contact with children. Nonetheless, the Archdiocese of New Orleans indefinitely suspends him from the clergy. His career as a schoolteacher is also over.

- 1998: George Brignac joins the Knights of Columbus, a Catholic community service fraternity. The organization lets him hold a number of positions during his two decades of membership, including ones typically reserved for priests.

- 2002: After a Boston Globe investigation shows the worldwide Catholic Church covered up thousands of cases involving clergymen who had molested children, then-New Orleans Archbishop Alfred Hughes makes Brignac’s indefinite suspension from ministry a permanent one. Hughes asks Brignac to voluntarily leave the clergy, but Brignac refuses.

- 2009: The Rev. Robert Massett, then pastor of St. Mary Magdalen Church, invites Brignac to read at Masses as a lector. Brignac -- whose Knights of Columbus chapter is based at that church -- undergoes training to prevent child abuse and report instances of it. He discloses on paperwork that he had previously been arrested and fired from jobs for child abuse allegations, yet he is allowed to complete the training and Massett signs off as Brignac’s supervisor.

- Circa 2011: Brignac begins taking an interest in an altar boy in a wheelchair, trying unsuccessfully to persuade the child’s mother to let the boy come over to Brignac’s home. Massett says he believed Brignac only spoke once to the boy before a parent put an end to it.

- 2013: The archdiocese quietly pays an $88,500 settlement to a man who first came forward with an abuse complaint against Brignac in the wake of the 2002 scandal. The settlement amount remains secret for the time being, with the archdiocese saying the victim requested confidentiality.

- 2017: In his role with the Knights of Columbus, Brignac speaks to a group of children at St. Mary Magdalen about a century-old miracle in Portugal and helps organize a special commemorative service featuring children.

- 2018: The Archdiocese of New Orleans pays a $550,000 settlement to a man who was an altar boy when Brignac was in charge of the altar boy program at Our Lady of the Rosary and was a student of Brignac’s at the school there. He claims Brignac raped him and otherwise molested him regularly between 1978 and 1982, at Brignac’s house and in his car. The man and his attorney, Roger Stetter, speak publicly about the settlement, prompting more accusers to come forward. At least 15 other Brignac victims receive settlements from the archdiocese totaling roughly $3 million. Meanwhile, Archbishop Gregory Aymond in November releases a list of 57 priests and deacons faced with credible child sex abuse allegations. Brignac’s name is first on the roster, which spurs another wave of abuse claims against the archdiocese.

- 2019: New Orleans police arrest Brignac on a count of first-degree rape after speaking with the recipient of the $550,000 settlement and another alleged victim who accuses Brignac of molesting him -- and ultimately raping him -- beginning when the victim was as young as 3. Prosecutors file charges. Brignac, who faces a mandatory life sentence if convicted, makes bail and pleads not guilty. Prosecutors line up roughly two dozen other men who are prepared to testify that they, too, had been preyed on by Brignac, including victims who had settled their cases, had pressed the earlier criminal cases, or were newly identified. The victims report abuses over nearly three decades, from after his 1960 dismissal from the Christian Brothers to shortly before his 1988 suspension of duty as a deacon.

- Spring 2020: A courthouse closure caused by the coronavirus pandemic dashes victims’ hopes that an aging, increasingly frail Brignac might be tried quickly. The Archdiocese of New Orleans, citing financial strain, files for bankruptcy protection.

- June 29, 2020: Paramedics rush Brignac, 85, from an Uptown nursing home to Touro Infirmary. He’s short of breath and goes into cardiac arrest in the ambulance. He is pronounced dead soon after his arrival, sparing Brignac from ever facing criminal punishment.