Jamal Cox was 29 years old when St. Tammany Parish deputies say he fled from them on a dirt bike in a quiet Slidell subdivision.

The chase lasted less than 10 seconds, covering barely more than a block. Deputies say Cox ditched the motorcycle after crashing into an empty parked school bus, jumped a fence, then ducked into his family's Slidell home.

He was taken into custody without incident, but this seemingly low-level crime ultimately landed Cox in prison for life, without the possibility of parole.

“When I first got the case I was shocked,” said attorney Rachel Yazbeck, who represented Cox on appeal. “You're like, is he really facing life over this? It’s just so petty.”

Complicating matters for Cox were his two prior felony convictions.

Cox received probation for simple burglary when he was 19. A decade later in 2009, he received probation again after pleading guilty to illegal use of a firearm.

For the brief motorcycle chase, the St. Tammany District Attorney’s office charged Cox with aggravated flight from an officer, a felony punishable at that time by a maximum of two years in prison.

Prosecutors offered Cox a plea deal for five years, but he turned it down, choosing instead to go to trial. He said he didn't think a one-block chase on a dirt bike in which nobody was hurt was worth five years behind bars.

After Cox was convicted by a jury, prosecutors used his two prior convictions to have Cox sentenced under Louisiana's multiple offender law. Instead of facing the two-year maximum sentence for aggravated flight, Cox was sentenced to life by Judge William Crain.

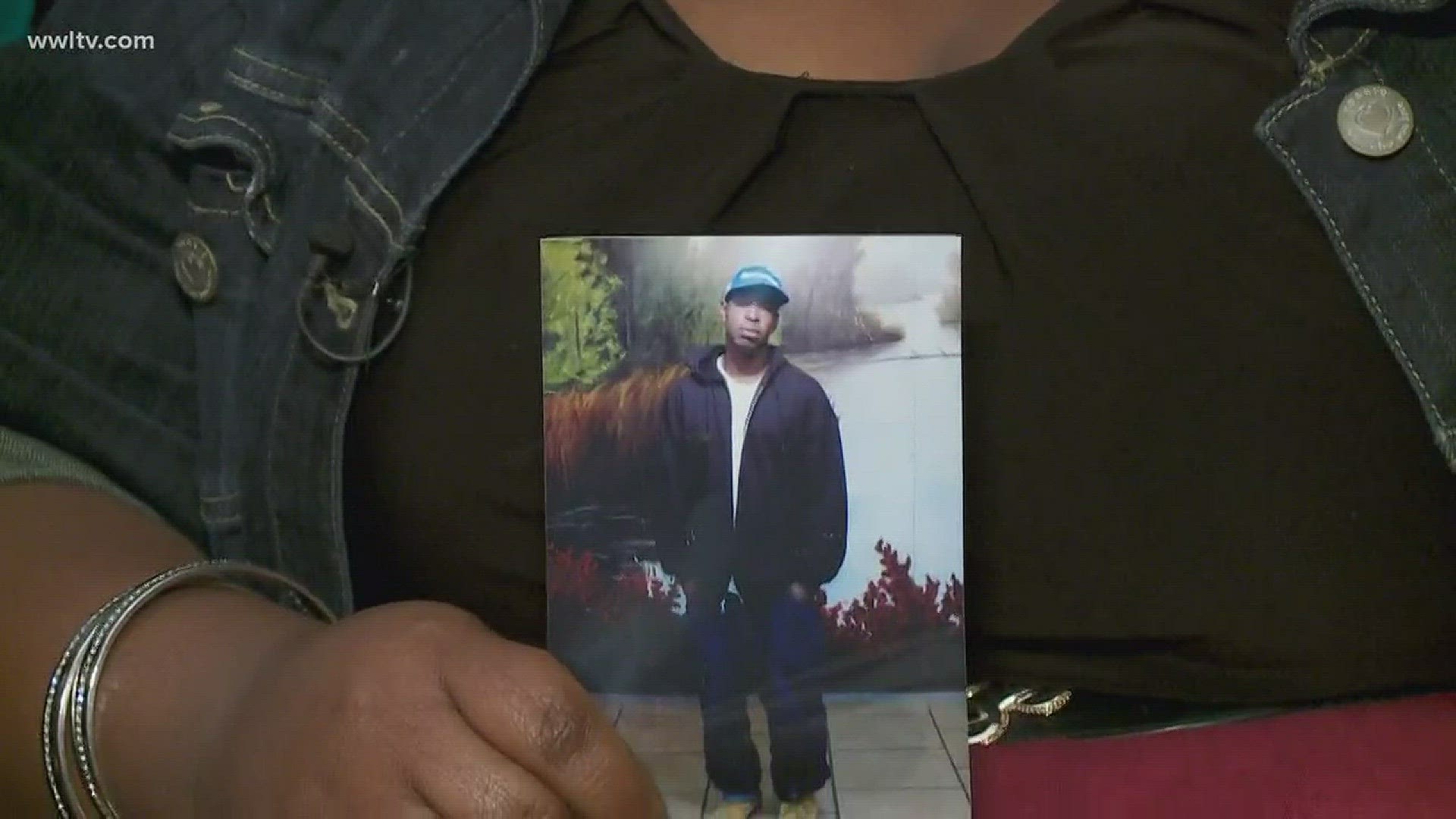

His family and friends were crushed.

“It's heartbreaking. It's heartbreaking because you're just helpless,” said his sister Ingrid Cox. “I have no faith in the justice system anymore because it doesn't work.”

His mother, Lorraine Cox, took the sentence especially hard.

“How do you make a life sentence out of that?” she asked tearfully. “How do you say you'll never see freedom again? How do you say you'll never see your mother again?”

Cox was represented at trial by a public defender. He said that after the five-year plea deal was offered, the attorney didn't fully explain a critical date on the calendar.

To be sentenced as a multiple offender, the crimes must be less than 10 years apart. Cox said he didn't realize that his second conviction, the gun case, was seven days from being outside of that limit.

“Two years versus life, yeah, that’s what it amounts to,” Yazbeck said. “There are some people that deserve to be in jail for life. But no, not this guy.”

A group of Cox’s friends, some from childhood, have organized to bring attention to his plight.

Longtime friend Aisha Smith said she is baffled that some people convicted in killings and other violent crimes can be released while Cox, and others like him, remain stuck behind bars.

“He committed no murder. He committed no rape. He sold no drugs,” Smith said. “There's nothing dangerous about him. How can the law that is supposed to protect people, to maintain order, do something that's so out of order?”

A set of new laws designed to lower Louisiana's incarceration rate, the highest in the nation, took effect on Nov. 1. Called the Justice Reinvestment Act, the reforms included changes in the multiple offender statute, reducing the time window between felonies from 10 years to five.

Under the new law, Cox would be free today, but the law is not retroactive.

“What we're really seeing is the disparity between what the law imposes and what we think is actually right and morally correct,” said Loyola Law professor Andrea Armstrong, who advocated for the sweeping sentencing reforms.

She said Cox’s case “really raises serious questions.”

“I think the first thing you need to think about is, what does it cost us to keep him in there for life without parole?” Armstrong asked. “And is that cost worth it?”

WWL-TV spoke to Cox by phone from the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola, where he has earned his GED, became a master furniture maker and now tutors other inmates as a Class A trustee, a status reserved for inmates with clean disciplinary records.

“It's almost like a death sentence. Like being caged,” Cox said. “For something that lasted, what was it, no more than six seconds? I've been sentenced to death. That's what it feels like.”

Walter Reed, district attorney at the time of Cox's case, is no longer in office. Judge Crain now sits on the 1st Circuit Court of Appeal, that court denied Cox's appeal in 2012.

The three-judge appellate panel – consisting of judges Vanessa Whipple, John Michael Guidry and James “Jimmy” Kuhn, who retired in 2014 – agreed with Crain that the sentence was not excessive. The panel reiterated Cox’s additional misdemeanor convictions, which included DWI, driving with a suspended license and open container.

“The trial court’s thorough review of this matter convinces us that the sentence is not excessive,” the appeal court panel wrote. “The defendant has repeatedly engaged in criminal behavior nearly half of his life. It seems that no amount of time spent incarcerated or on probation, up to this point, has diminished the defendant’s propensity for breaking the law.”

Current District Attorney Warren Montgomery, in office since 2015, refused to talk about the case.

Unless there is change in the law or a successful long-shot appeal, the only chance for Cox to get released is a commutation of his sentence by the Louisiana Pardon Board.

He is not eligible to apply for a commutation until he serves 15 years in prison. So far, he has served seven.

Cox said he tries not to dwell on his situation, choosing instead to find ways to better himself behind bars. Just recently, he has started taking college courses.

“I spend most of my time trying to educate myself as best as I possibly can,” he said. “Any trade that I can pick up, I try to pick up… I just can't sit here and wait to die. I can't wrap my mind around that.”