NEW ORLEANS — The cries for help, the gasps for breath just out of reach, they’re gut wrenching to hear in videos that have been surfacing in recent years of people dying under the weight of police officers, laying face-down with their arms handcuffed behind their back.

Even before George Floyd died face-down and breathless with the knee of a Minneapolis Police Officer to his neck, Keeven Robinson, 22, died in a similar way in a Jefferson Parish backyard on March 10, 2018.

Many law enforcement officers across America are trained to put suspects in a prone position, again, face-down, with their hands cuffed behind their backs, in order to gain control.

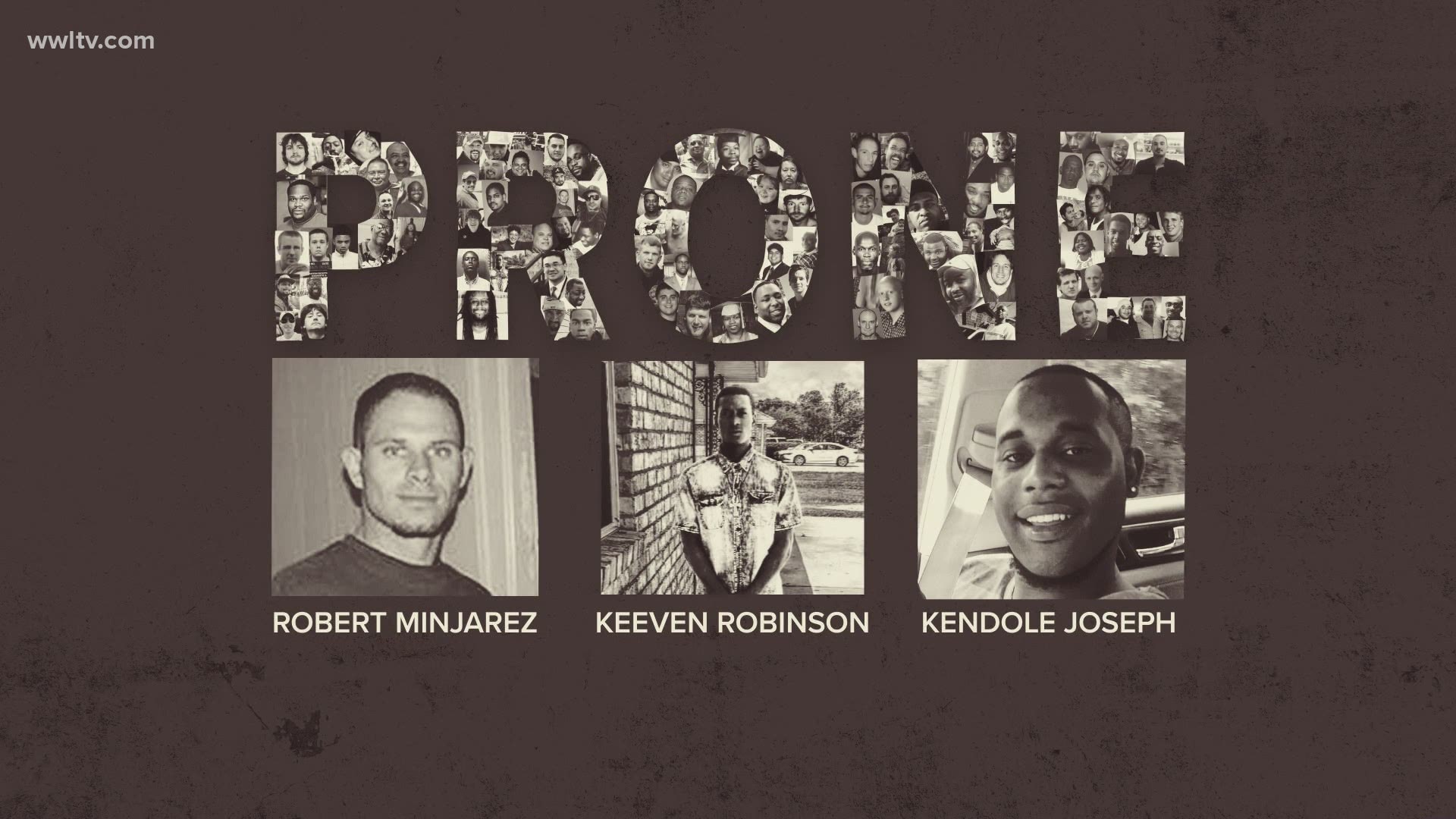

But a national investigation by TEGNA, the parent company of WWL-TV, found a prone restraint turned deadly for more than a hundred people nation-wide over the last decade, at least three times in Louisiana alone.

Included in the 107 deaths TEGNA investigators documented through court filings and media reports are the deaths of Keeven Robinson, Kendole Joseph in Gretna and Robert Minjares near Lafayette.

Law enforcement experts and trainers say a prone restraint is a good way to subdue an aggravated suspect, but there’s a catch.

“I think prone restraint is actually a very valid and reasonable tactic to accomplish restraint because we have to try to do it as safely as we can,” said nationally-recognized law enforcement trainer Jack Ryan.

Once the suspect is handcuffed and is no longer a threat, however, Ryan and other experts interviewed said it’s essential to move them off their stomachs.

“Immediately move them into a position… that facilitates breathing,” he said.

Get off of them, turn them over, sit them up and above all, Ryan said, watch for signs of positional asphyxia. The U.S. Department of Justice began warning law enforcement agencies about the potential risk of it in 1995. A flyer distributed at that time defines it as, “…death as a result of body position that interferes with one's ability to breathe.”

Ryan said moving the suspect to facilitate breathing would not put the lives of the arresting law enforcement officers at risk.

But 25 years after the DOJ’s warnings, the deaths have continued.

Published reports say Robert Minjares, Jr. had a history of mental illness and a cocaine addiction and in March of 2014, a convenience store clerk called police after Minjares was pacing around the parking lot appearing anxious and paranoid.

A federal civil rights lawsuit filed on behalf of Minjares’s family says three police officers sat on his upper body and his legs after they hand him handcuffed face-down in a prone position.

The dash camera from one of the police units on the scene captured the audio of the incident. Five minutes in, as you hear Minjares making his guttural, final pleas for the officers to get off of him, one of the officers warns him to stop struggling.

An unidentified police officer can be heard saying, “265 pounds on your back. You not going anywhere.”

Minjares suffered from the two biggest commonalities among all the deaths identified: drug addiction and more so mental illness.

Kendole Joseph battled it too. He himself had called 911 twice the day he died asking for help getting the "fake police" away from him. His mother, Debra Guillory, called police asking for help with Joseph.

“I called them and told them my son is paranoid schizophrenic. I said he is on Manhattan and I don’t want him to get hurt ‘cause you know he was crossing the highway,” Guillory recalled.

After the police showed up, witnesses said Joseph ran inside a West bank convenience store. Surveillance cameras captured multiple angles of what happened next.

Joseph jumped over the check-out counter and police followed one after the other.

According to court documents, witnesses said Joseph called out for his mother during the struggle. Those same documents say police shocked Joseph with a stun gun, beat him with a baton, which you can see in the video, and then held him down to get the handcuffs behind his back.

Joseph had committed no crime and was not a suspect.

The video shows the officers carrying Joseph out of the store face-down, in a prone position. A federal civil rights lawsuit filed by the Joseph family against the Gretna Police officers says they placed Joseph in the back of their squad car face-down.

“He had both kidneys fail, liver, his heart failed. And he had brain damage,” Guillory said.

Their lawsuit is still pending. But one of the issues raised was whether the officers should have known the dangers of placing Joseph in the squad car in a prone position.

In recent years, as court records show the police officers have argued in the Joseph case, some law enforcement officers have called on experts who question the science behind prone restraints as a cause of positional asphyxia.

One of them is Dr. Gary Vilke of San Diego, California.

“That position is physiologically neutral,” said Vilke in an interview with KUSA in Denver.

He testifies regularly that his research has shown the human body can withstand having bodies piled on top of it and that most of the suspects die of sudden cardiac arrest.

But other researchers over the decades have found the cardiac arrest is caused by the struggle and the person’s inability to breathe -- the asphyxiation.

Many courts have recognized that positional asphyxia is a concern through their rulings in the many civil rights lawsuits that have been filed against law enforcement officers after someone dies.

INTERACTIVE GRAPHIC: Click on the photos below for more information on the dozens of people who died in police custody after being held in a prone position, and the settlements their families received, built by our partners at 9News.

Of the 107 prone restraint deaths identified, the resulting lawsuits have cost law enforcement agencies across the country more than $70 million.

The U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana currently oversees the New Orleans Police Department’s consent decree, a roadmap to turn around a problem-plagued department.

The consent decree re-wrote the NOPD’s use of force policy to better promote constitutional policing. It tells officers how and when to use force against criminal suspects and it warns “death may occur” from positional asphyxia.

The document also clearly states that neck holds, including kneeling on a suspect’s neck, are considered lethal force.

A Minneapolis Police Officer held George Floyd in a neck hold in the agonizing video of his death.

Demone Robinson, Keeven Robinson’s cousin, said watching it hit home.

“As I was watching the video, I saw Keeven's face on George Floyd's body and it seemed like they that's exactly what they done Keeven.” Demone said. “I broke down in tears the moment while watching that video and it's just like a repeat all over again because nothing is being done about it.”

Jefferson Parish Deputies said after surveillance operations, they suspected Keeven had been dealing heroin and other drugs and the day he died, they had planned to arrest him.

When they approached Keeven at a gas station, surveillance video shows Keeven took off. Later, they crashed and Keeven ran from four narcotics officers.

The day it happened, another of his cousins, said in an interview, “He told them he was tired. So why did you beat him?”

When they caught up with Keeven in the backyard of a home, the officers said they didn't know if Keeven was armed and they struggled to take him down. As they tried to handcuff him in a prone position, three officers held him down. An autopsy by the Jefferson Parish Coroner and a forensic review of that autopsy commissioned by the Jefferson Parish District Attorney found Keeven couldn't breathe.

The transcript of an interview with JPSO internal investigators reads that Deputy David Lowe told them, "At one point, I remember kneeling on his head. I don't remember if I had both knees on his head, if I had one knee on his neck, if my hand was on his neck, but I do, I do remember my main focus was pinning his, pinning, his head to the ground.”

The investigating deputy then asked if that was to keep Keeven from trying to get up and Lowe responded, “Yeah.”

Coroner Gerry Cvitanovich said the autopsy found injuries consistent with compressional asphyxia.

He ruled Keeven’s death a homicide. But both Jefferson Parish District Attorney Paul Connick and the U.S. Department of Justice declined to prosecute the officers for Keeven's death.

In a report released last summer, Connick said the JPSO’s use of force was “legally justified.”

Jefferson Parish Sheriff Joe Lopinto said he was going to conduct an internal review to determine if the officers violated JPSO policies. A spokesman for Lopinto did not respond to questions about whether that was done and what the sheriff found.

To the detectives on the day he died, Keeven was a suspected heroin dealer, but in the 22 years leading up to that day Keeven was, and frankly, will always be part of a tight circle of cousins.

Kaitlynn Moran said they would text each other regularly and Keeven’s last words to her were, “that he loves me, we always told each other."

His cousins all said Keeven was loyal, funny, that he loved to laugh and make them laugh. Every time they talk about how he died, they said, it hurts but they keep doing it for a reason.

“No matter what his background was, no matter what the media paints him out to be, he was still our loved one, you know, still somebody we loved and loved us. We knew who he was. To us," Moran said. "Nobody deserves to die the way that he did. They had no right doing what they did to him.”

Of all the cases of prone restraint deaths documented, 68% of those who died were not white. Many were black, Hispanic and Native American.

The disparity of it in a country that’s 60% white is one of the reasons Moran said she has been taking to the streets, protesting for racial justice and justice for Keeven.

“It's about the importance of, you know, black people's lives. If it mattered to them, they would have took an extra step to not take his life. They did it on purpose. That was their intention. And that's just the bottom line,” Moran said.

Law enforcement use of force policies across Louisiana, and the country, are inconsistent. Different agencies use different established methodologies for how to use force and when it’s appropriate.

“The type and use of prone holds is subject to the defensive tactics course being taught and whether the law enforcement office itself has adopted one or more of the defensive tactics systems as a policy for that department/office,” said Bob Wertz, the Law Enforcement Training Manager for the Louisiana Commission on Law Enforcement.

He said the Department of Justice is currently surveying all law enforcement agencies that are eligible to receive federal grants to sort out which agencies have use of force policies and what those policies say.

When it comes to prone restraints, the more than 100 deaths documented over a decade and the simple solution of turning suspects over to facilitate breathing, a former New York City Police Detective who heads up the Black law enforcement alliance said what we found is “inexcusable.”

► Get breaking news from your neighborhood delivered directly to you by downloading the new FREE WWL-TV News app now in the IOS App Store or Google Play.