COVINGTON, La. — Some family members of residents at Forest Manor Nursing & Rehabilitation in Covington, one of the Louisiana nursing homes hit hardest by COVID-19, say they believe better administrative decisions, like isolating symptomatic residents and additional staff, may have slowed the spread of the virus at the facility.

The families of Thomas Zanco, Carolyn Fowler, Sheila Pierce, Venida Huffer and Joy Thomas all wonder if their loved ones might still be around if the home’s infection control had been handled better in the early days of the pandemic.

The daughter of Forest Manor’s first COVID-19 victim, Sheila Pierce, 60, was so concerned about the facility’s response after her mother passed away that she sent an email to the Louisiana Board of Nursing.

Daughter of COVID victim: Home was slow to act

“They did not quarantine her. They did not move her roommate. They did not take any extra precautions, despite the severity of this virus and her displaying ALL the symptoms,” writes Pierce’s daughter Angela Pierce Hill.

The Louisiana Board of Nursing does not oversee nursing homes, just the nurses who work in the facility. But Hill said she thinks her concerns fell on deaf ears. No one ever responded to her.

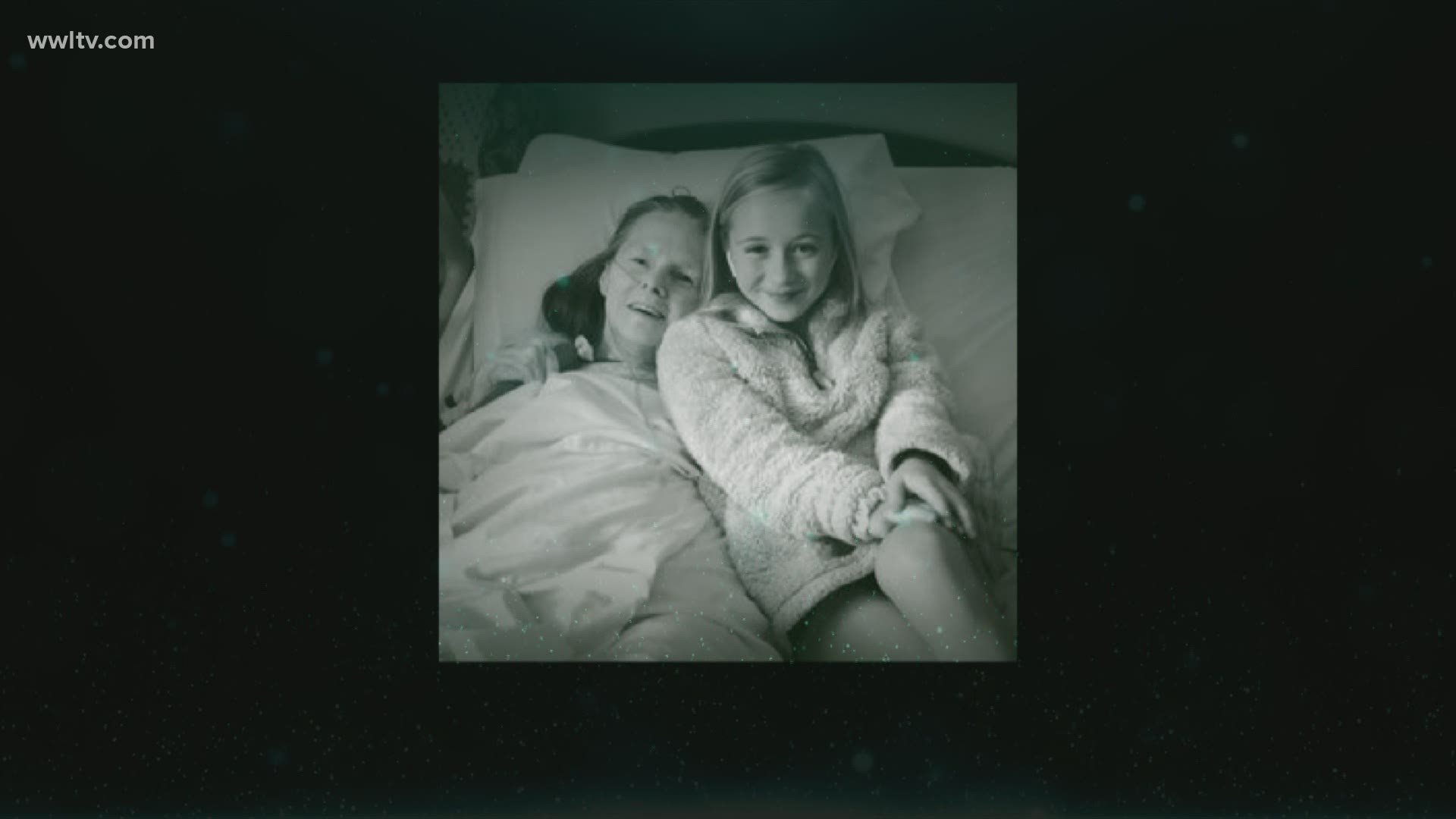

Pierce passed away April 5. Hill said her mother started experiencing symptoms of COVID-19 on March 14. She was congested and had a fever.

Pierce developed pneumonia two days later and even though Hill asked for her mother to get a COVID test, that didn’t happen until the following Saturday, March 21, when her symptoms had gotten so bad she was taken to the hospital.

All that time, Pierce was not isolated at Forest Manor as if she had COVID and according to Hill, she had a roommate.

“We love and miss her so much. I know there is nothing that will bring her back, but something needs to change before more lives are lost,” Hill said. “Someone should be held accountable for the way things were handled. New protocols need to be in place and the staff needs better training on how to care for contagious patients.”

Pierce’s test came back Tuesday, March 24. That’s the same day Forest Manor Administrator Clay Pere sent an email to family members reassuring them that a resident had tested positive at the hospital, but was not in the facility. Again, Pierce’s daughter said she had been coughing for six days before she went to the hospital.

“She had some really amazing nurses there and of course, some bad apples from time to time. I do believe the in-house staff were doing everything they were instructed. But those in higher positions of authority that were handing down those instructions dropped the ball big time, and with deadly consequences,” Hill said.

Pere did not respond to repeated phone calls and emails seeking comment for this series.

Other Forest Manor families shared similar concerns. Venida Huffer died of COVID-19 on April 12, Easter Sunday.

Venida had been moved into a room with another woman on the 500 hall, the section of Forest Manor that would become the COVID isolation wing. Venida’s roommate was on hospice care, days from passing away.

Numerous family members were allowed to come into the room and see the dying roommate during the lockdown, possibly putting Venida at risk.

She tested positive for COVID-19 three days later.

"I tragically had to watch my mother suffering and dying sitting on a foldout chair outside her window sobbing and trying to be heard over the a/c unit,” Whitney said.

Nurses and staff praised

Other Forest Manor family members have applauded the home's scramble to access testing in short supply though a nearby urgent care clinic and hunt for personal protective gear once Forest Manor's supply ran short, sewing sleeves onto hospital gowns for staff.

A number of residents’ families were grateful for kindness after kindness shown by nurses and staff filling in for loved ones who were locked out.

The horror of having a loved one in a nursing home during the pandemic isn’t unique to Forest Manor. More than 2,400 families across Louisiana could tell similar stories of saying their final goodbyes through a video call.

But some families of nursing home residents say the good came with the bad, and the overwhelmed staff made some patients suffer.

Dede Magee said she hopes her husband won’t be one of the ones saying goodbye through a window. Joe, 83, is now a resident at Pontchartrain Healthcare Center in Mandeville, after a weeks-long stay at Forest Manor.

“That's my heart, my best friend,” she said about her husband of 20 years. “He's a good man, he deserves a whole lot better than what he's getting.”

Joe hurt his heel last spring. He's a diabetic, so the bruise turned into an infected sore. She said Joe had surgery on it and ultimately ended up at Forest Manor for rehab to try and walk on it again.

A few weeks into his time there, a nurse called Dede.

“At this time, he was telling me, your husband is in such poor health instead and I'm like, baby, you can't be talking of the same man that I put in there because he didn't go in there like that,” she said.

Like so many others, she was locked out, locked away from her best friend.

“He’d be like, 'baby, sometimes, they're mean to me,' you know, and you can't do anything for him. You can't do anything for him,” she said choking back tears.

RELATED: Many nursing homes were already short staffed and then the staff got COVID - disaster ensued

"Get him out of here right now"

In August after a confusing trip to the cardiologist to check for a blood clot in Joe’s leg, Dede said Forest Manor called wanting to send Joe back to the hospital because they found a severe bedsore on his backside. It’s a pressure sore that develops when people lay in the same position for a long period of time.

“I said, get my husband up and get him out of here right now, get his clothes on, get him up and get him out of here right now. And we took him to the hospital,” Magee said.

“I think a lot of people were not being fed properly. They weren't being exercised and gotten out of bed. So then that's what leads to pressure ulcers,” said nationally-recognized nursing home expert Charlene Harrington, a researcher and University of San Francisco Nursing professor.

Medicare records show Forest Manor can house 192 residents. State health records show the facility’s resident population dropped to 112 in mid-July. Insiders said some Forest Manor staff members were laid off around that time.

“We don't have an adequate financial oversight to see where the money's going. I mean, it's true that the occupancy has gone down and so on, but the staffing rates are too low to begin with, so they shouldn't be laying off staff,” Harrington said.

As of last week, Forest Manor's population was back up to 134 and an online job posting indicates they are once again looking for nurses, now offering a $1,000 signing bonus. Other nursing homes are offering bonuses too--an indication nurses and aides are hard to find.

Medicare ratings for staffing at Louisiana's nursing homes are low, with a majority of homes rating below or well-below average for the time nurses and staff spend with each resident. Experts say part of that is the result of low state staffing requirements.

“We know you need to have 4.1 hours per resident per day in total staffing,” Harrington said.

Louisiana law requires nursing homes provide just over half that, 2.6 hours spent with each resident every day.

The Louisiana Department of Health said that requirement only applies to Medicaid recipients, which make up the vast majority of nursing home residents, and without giving specifics a spokesperson said there are other staffing benchmarks state inspectors look for.

“The easiest way to make money is just to keep your staffing very low,” Harrington said.

Tax dollars—in the form of Medicare and state Medicaid--are the largest source of income for nursing homes.

Medicaid pays different daily rates to different nursing homes based on a formula spelled out in state law. Right now, Forest Manor has the highest Medicaid reimbursement rate of any nursing home in the state: $234.11 a day.

That includes a $12-a-day bump all nursing homes are getting right now to help pay the increased cost of fighting COVID.

They're also getting more money to hold beds for residents who leave the facility and go to the hospital, for example.

Pre-COVID, the state only paid them a portion of the daily rate for those empty beds. But right now nursing homes are getting the full day rate, plus the COVID surplus.

Still, the nursing home industry has long said their regular Medicaid reimbursement rates don't come close to covering the total cost of care for their residents.

The American Health Care Association represents nursing homes and said, “Since the beginning of the pandemic, we have urged policymakers to help long term care facilities with resources to support our health care heroes, such as personal protective equipment, funding to help offer staff 'hero pay' and hire additional staff, as well as policies that help address workforce needs."

While many of Louisiana’s nursing home residents need the round-the-clock care they provide, some don't.

“The human cost is extraordinary. Forty percent of the deaths have been centered in nursing home and institutional living environments. We can cut down those numbers significantly if we keep people at home,” said Executive Director of Tulane’s Public Law Center, David Marcello.

In home care could provide an answer

Right now, nearly 10,881 people are on a waiting list to be able to get in-home help paid for by Medicaid, according to LDH. To get it, people have to get what's called a community choices waiver. The state only grants a limited number of them, which is why there's a waiting list.

About half of the people on that list had to go into nursing homes or get some other type of services because it can take years to get a waiver.

“The real problem, other than depriving someone of being able to be cared for at home, is that it's going to be a fiscal nightmare in our state,” said Pres Kabacoff, a businessman who takes up social causes.

He’s working with the AARP and a group of advocates pushing to give more Louisianians the chance to age at home.

Experts say the waiver services cost half of what a nursing home stay does. The AARP estimates an annual stay in a Louisiana nursing home is, on average, $52,191.

Ultimately the governor controls how many community choices waivers there are in the state budget. Last year, LDH said they added 500 more. A spokesman said in a statement, "In 2019, LDH assisted more than 300 residents with transitioning out of a nursing facility; during COVID-19, LDH has transitioned 115 people out of nursing homes, despite barriers to visitation."

Governor Edwards’ Press Secretary said, “Since taking office it has been among his top priorities to support and help individuals and families receive services in the least restrictive environments.”

Since 2017, his administration has worked to move about 16,000 people off the wait list, but still, nearly 11,000 remain on it.

“I see it a little bit differently than before COVID when I was trying to pass the law. It was really quality of life. I felt simply that if someone was well enough and had it was of a mind to want to stay home, they should be allowed to stay home,” said former La. Sen. Conrad Appel, R-Metairie.

Now, for Appel, it can be a life-or-death choice.

“You're scared to leave your loved one in places like that now because you don't know what's going to happen to them,” Magee said.

Our nursing home system has been entrenched in Louisiana law, even the Louisiana constitution, with the help of the state's powerful nursing home lobby. He said money in the form of campaign contributions gives the nursing home owners and lobbyists access to lawmakers and decision makers.

“The law that I tried to change, which was the law that mandates that Medicaid folks can't get services unless they go in nursing homes was defeated. And I felt very comfortable when I say it was defeated because of the influence of nursing home owners and associations," Appel said.

The group of activists is pushing federal legislation sponsored by Sen. Bob Casey, D-Pennsylvania, that would add a separate federal revenue stream for Louisianians to get in-home services instead of going into nursing homes. Currently, it’s part of the negotiations going on over the next round of CARES Act funding in Washington.

It has little support from Republicans, something that is disheartening to Marcello.

“The ability to stay at home and age in place is not a red issue or a blue issue. It is a life and death issue, never more so than here in the midst of the pandemic,” he said.

So far, Louisiana’s nursing homes have gotten $150,520,550 in CARES Act provider funding to help offset the loss of revenue from lower patient populations and increased cost to fight the pandemic.

Forest Manor received $1,109,080.34. The AHCA is continuing to push for additional help from the federal government to fund frequent testing of residents and staff, PPE and help with staff.

► Get breaking news from your neighborhood delivered directly to you by downloading the new FREE WWL-TV News app now in the IOS App Store or Google Play.