Women incarceration rates drop as criminal justice reforms help women jailed for killing a domestic abuser get freed

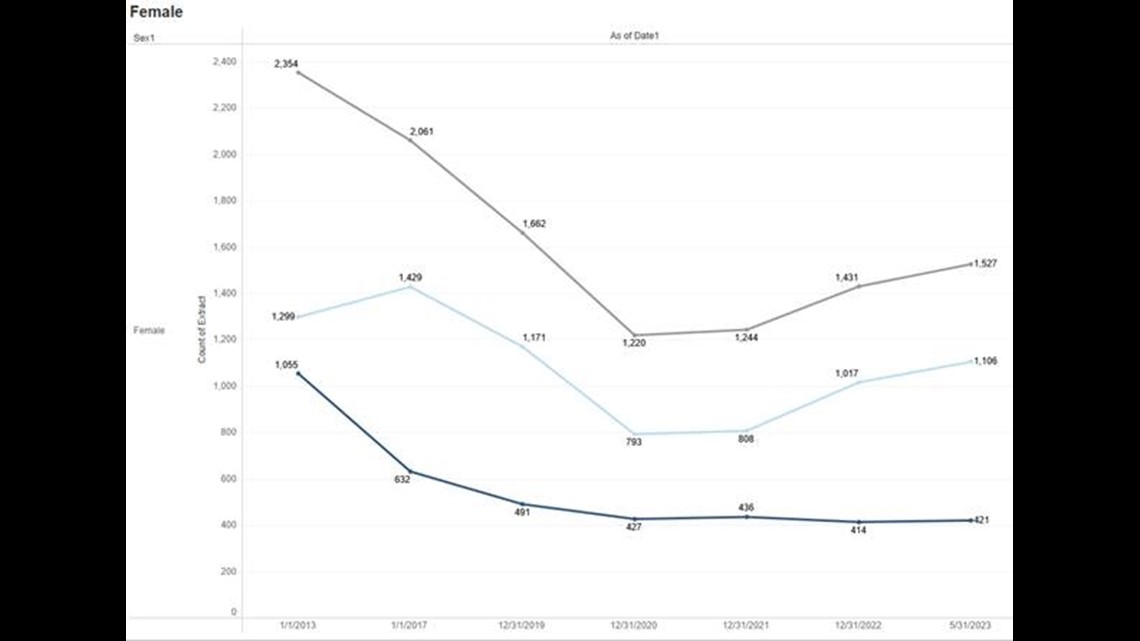

Population numbers from the Louisiana Department of Public Safety and Corrections show a drop from 2,345 women incarcerated in 2013 to 1,220 in 2021.

An increasing number of domestic abuse survivors are among the women who have been freed from Louisiana’s prisons in recent years as the state cut its female prison population nearly in half.

Criminal justice reforms, landmark court decisions affecting the rights of the accused and the work of advocates for women in prison have all played a significant role in shrinking a prison population that experts have long said was unfairly large.

Population numbers from the Louisiana Department of Public Safety and Corrections show a drop from 2,345 women incarcerated in 2013 to 1,220 in 2021. The population has since climbed back up over 1,500 but it’s still significantly smaller than it was a decade prior.

Women survivors of domestic violence, who claimed they killed their abusive partners in self-defense but were convicted by a jury anyway, are among those reaping the benefits of the state’s new-found mercy.

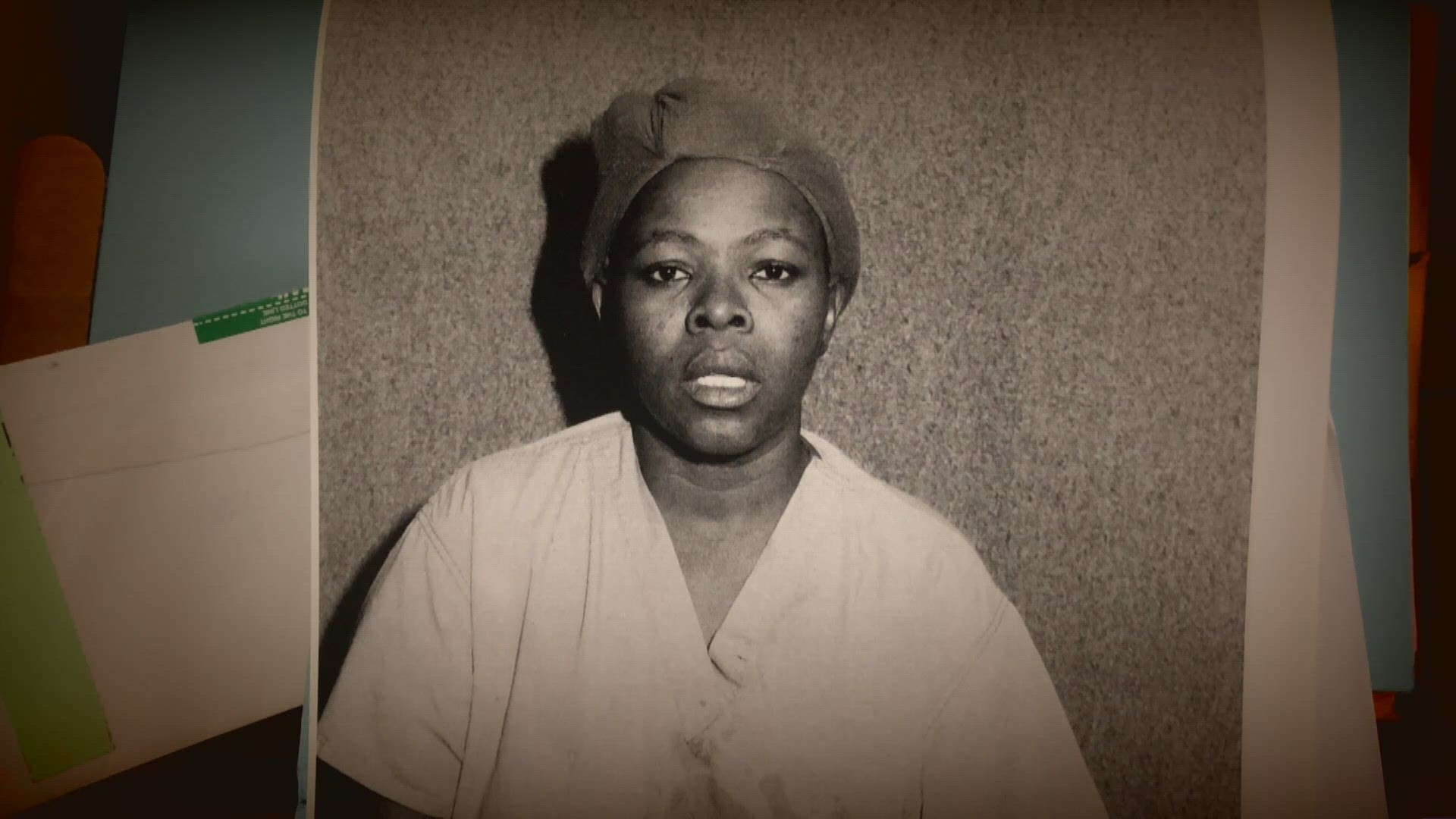

Laura Eugene

When Laura Eugene first went to prison after she killed her abusive boyfriend in 2000, their daughter DeVanna was only five years old.

The girl, now in her ’20s, said she spent her whole life looking for her mother.

“I remember looking for her at almost everything, graduation, high school graduation, prom and things. And I would look for her like, knowing she wasn't coming,” DeVanna said.

She was praying for a miracle to help her feel whole. She lost both her mother and her father the night David Fluence was killed.

His death resulted from the last fight in their tumultuous relationship.

“When the fights would happen, they would split up, get back together, split up, get back together, that sort of thing,” said Veronica Nicholson in 2018.

That’s when WWL-TV first profiled Laura’s case as part of an investigative report on women serving life in prison for killing their alleged abusers.

Laura’s sons recalled hearing their mother and Fluence fighting over the years. They both remembered hearing Laura banging up against the walls the night Fluence was killed.

“David started beating on her. So, I'm hearing the walls, like, boom, boom like,” Dwayne Eugene recounted when asked about the night of Sept. 1, 2000.

At such a young age, DeVanna doesn’t remember specifics.

“I don't remember all of the abuse, but I remember abuse. So, I know, I know that my momma didn't deserve this,” DeVanna said.

Police records that Laura’s attorneys say were never introduced at trial show Laura called the police on David 6 times over the years.

She was convicted by a non-unanimous jury and sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

But in 2017, Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards spearheaded the passage of a sweeping criminal justice reform package in the Louisiana legislature. At the time, Louisiana had one of the highest incarceration rates in the nation, and the reforms gave hundreds of inmates a second chance at life on the outside sooner than they ever thought possible.

Laura Eugene was one of them after Governor Edwards commuted her sentence to 99 years, making her eligible for parole under the new laws.

Four months after Edwards commuted her sentence in July 2022, Laura was granted a parole hearing. She testified before the Louisiana Board of Pardons and Parole, making her case for a release.

“I was trying to protect myself at the time and he throwed me down on the coffee table and choke me so I couldn't breathe. So, I realized that I got up and went and got a knife and I stabbed Mr. Fluence,” she told the board. “I take full responsibility for my actions for what I did to the family.”

Citing the clear history of domestic violence involved in Laura’s relationship with Fluenece, the board granted her parole and seven days before Christmas last year, the Eugene family got the greatest gift they ever could have imagined: a hug from Laura as she walked out of the prison gates.

“It really was a dream come true,” DeVanna said.

Women’s Prison Project Frees 10

“There's nothing more rewarding as an attorney, of course, than to see a client who has spent decades in prison walk out of those prison gates,” said Becki Kondkar, the Director of the Tulane Law School Domestic Violence Clinic and Co-Founder of the Women’s Prison Project.

Kondkar took Laura's case on as one of the first for the project nearly five years ago.

“All the joy associated with those moments is always tempered by the recognition of everything that was lost to them and their loved ones and their children during those decades in prison,” Kondkar continued, “So it's joyous and also tragic.”

She was there with tears flowing as Laura was released last December after the hard work she and attorneys like Stanislav “Stas” Moroz put in to find Laura a way out.

That was the goal of the project at its inception. The founders had received a multi-million dollar grant to take a fresh look at the cases of women serving long sentences in Louisiana prisons to help right the scales of justice that had long left victims of abuse criminalized.

Kondkar said the group started its work with the list of women identified in a WWL-TV investigative report as imprisoned for killing abusive domestic partners in self-defense. The reporting utilized hundreds of court records, media accounts and experts like Kondkar to identify 21 women out of 138 who were, at that time, serving life sentences in prison.

“There are some specific features of our state, I think, that make it particularly likely that survivors will be criminalized and wrongfully convicted for actions associated with their abuse,” Kondkar said. Those features include mandatory sentencing and laws that don’t adequately consider the abuse.

Kondkar says the actual list of abuse survivors in prison is likely much longer than 21, but each case takes extensive research to figure out what really happened and how their attorneys can help under current law.

“Cases that are old, there's no real good legal avenue to go back into court and say, hey, look, this was a wrongful conviction,” Moroz said. He was also one of Laura’s attorneys.

If her trial had happened today, it would not be considered fair by the courts, but the law doesn't allow her to go back to court to appeal.

She was convicted by a non-unanimous jury and attorneys for abuse survivors are now required to call experts to tell the jury about the effect repeated abuse has on their decision-making. Laura's trial attorney signed an affidavit saying he didn't.

“From our perspective in reviewing these cases and representing these clients from parishes all over the state, the reality is that these women are behaving rationally in the context of impossible choices,” Kondkar said.

That perspective is some of what survivors now have the right for juries to hear, so that people who may not have lived in the cycle of abuse can understand how it affects people.

“They have been facing that basically domestic terror for a large part of their lives but the trials will still often focus on, well, do you know that he was going to kill her right in that moment,” Moroz said.

The push to correct unjust or excessive sentences began in earnest with Gov. Edwards’ sweeping criminal justice reforms.

In less than 5 years, the Women’s Prison Project attorneys have helped get 10 abuse survivors out of prison, through clemency like Laura and by asking prosecutors to take a second look at their cases.

Candice Malone was another one of them. She was also convicted by a non-unanimous jury and didn't have experts in domestic violence testify in her trial.

“I feel like the best way out for me sometimes would have been if I just allow him to kill me. Because. It hurts thinking that I have to live the rest of my life like this. You know, I didn't plan for this to happen. I didn't mean for this to happen. If I could take it back, I would just go back as far as not having ever met him,” Malone said in an interview after she was released.

Two other abuse survivors on WWL-TV’s original list had their cases re-considered by Orleans Parish District Attorney Jason Williams: Deborah Thomas and Idosia Robinson.

In all, 9 of the women WWL-TV identified have gotten out of prison.

Changing Laws

“They don't deserve to live forever behind bars for defending theirself,” DeVanna Eugene said.

She has been supportive of efforts by Moroz and other activists to try and change the laws that allow so many abuse survivors to be convicted and locked up.

“Our criminal legal system focuses on a snapshot in time. We need be looking at the big picture,” Moroz said.

Advocates pushed a new law aimed at expanding Louisiana's self-defense statute to better consider domestic abuse situations, but it failed to pass the legislature this year. It would've also given abuse survivors in older cases the right to appeal their convictions.

“We talked to the district attorney's offices all across the state about these cases and with a couple exceptions, we just haven't seen district attorney's offices willing to take a second look at these older cases,” Moroz said.

While prosecutors supported some of the reforms in the proposed law, their trade group, the Louisiana District Attorneys Association, opposed the section allowing people with older convictions to appeal.

Changing Attitudes

Whether they are successful in the future at getting what they feel is a more just law on the books, it won’t change biases against women and beliefs about domestic violence in society that advocates admit are deeply ingrained.

It’s evidenced by the first question survivors typically get asked: why didn’t you leave?

“The biggest question they ask is, why didn't you leave? And I left several times. I wanted to leave that day, you know, a lot of my time in prison I asked, why didn't he leave? He had every choice to not be the person he was, to not put his hands on me, to not threaten my life. And he chose not to do that,” Malone said

One of the members of the Louisiana Board of Pardons and Parole asked Laura that very question during her parole hearing.

“I know I was being crazy, being stupid, and I was in love and I just wanted him to stay with me and stay with the kids,” she replied.

In the end, DeVanna will never have her father again, but having her mother back home is giving DeVanna some peace.

“It pulls strings in my heart. Because sometimes I find myself staring at her playing with them, you know, to get them ready for bed. She's the big help with me now,” she said.

When her 4-year-old daughter, Ava graduated from preschool earlier this year, her Maw Maw, Laura, was in the audience watching Ava up on stage.

“I almost cried too, because like I say, my mom wasn't there for mine,” DeVanna said.

She’s no longer looking for her mother in the distance, she looks at her across the living room, snuggling up on the sofa at night with her two grandbabies.

► Get breaking news from your neighborhood delivered directly to you by downloading the new FREE WWL-TV News app now in the IOS App Store or Google Play.