'They were not raised that way' - Deadly carjacking devastates two families

Jeannot Plessy’s death in November 2018 came at a time when her life had undergone a renaissance

When pastor Jeannot Plessy was murdered in her driveway, run over by a teen-age carjacker and left to die in the street, it devastated two families: Plessy’s and the family of Jontrell Robinson, the young man who admitted to killing her.

Three teens were convicted for their respective roles in the Plessy murder, Jontrell, his brother, BoAvanti Robinson and their cousin, Edwin Cottrell. But the story didn’t end with the signing of their guilty pleas. It took an ironic and tragic turn in May of this year when BoAvanti was killed in a car crash, left to die in the street by two of his friends.

Plessy's Family

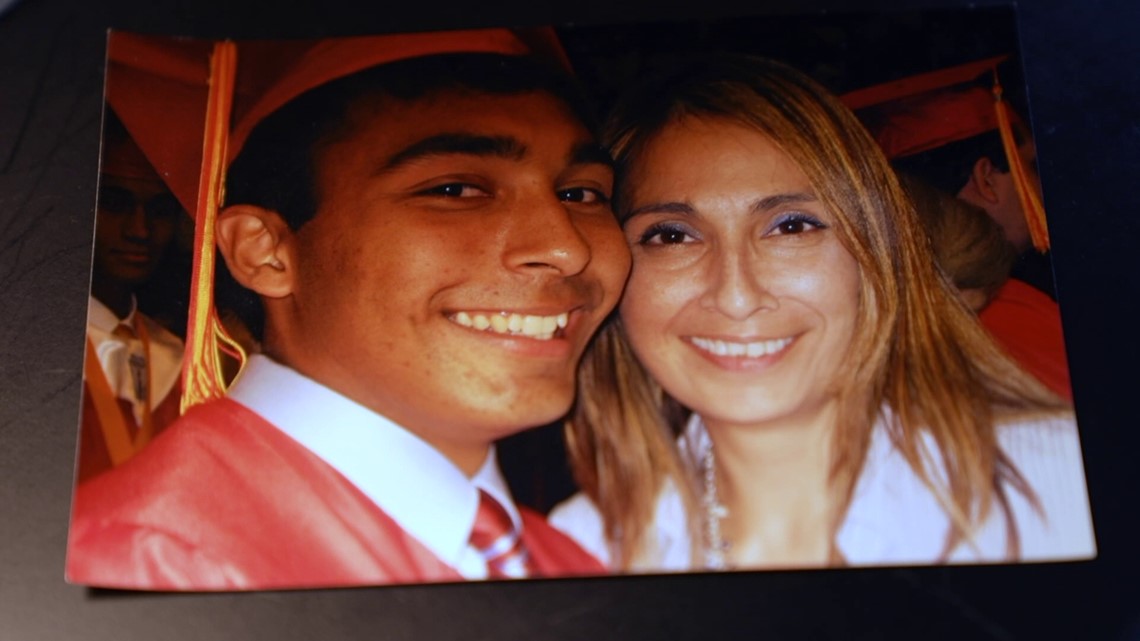

Jeannot Plessy’s death in November 2018 came at a time when her life had undergone a renaissance. A teenage mother, she struggled with an alcohol addiction and abusive relationships, but a renewed faith in God and the help of her own mother allowed Plessy to pull herself out of a difficult time.

She turned her attention God, regularly making red beans and rice to serve in underserved communities, meeting people where they lived. Jeannot and her husband, David, started their own church and had just returned from a mission trip where she spoke to women about domestic violence and leaving abusive relationships.

“She just seemed like so exhilarated and excited about what was next,” recalled Jeannot’s daughter, Nadia Sanchez, “It's really sad for me to think about how her life ended. It just seems like such a dichotomy of events to go from being so hopeful and joyful and looking forward to the future and just having your future robbed from you in such an unexpected way.”

Sanchez had been watching her two younger siblings the night Jeannot was killed. The carjacking happened in her Gentilly driveway when Jeannot got out of the car to go into the house and get them.

“If I could have gone outside sooner, if I could have dropped the kids off instead of having her pick them up, if I could have… you know… those thoughts last for years,” Sanchez said, “I don’t want to say forever. I hope not forever, but longer than I think people imagine.”

Sanchez’s husband was also hit by the car trying to stop Robinson from driving away. He had a brain injury that Sanchez says changed him forever. But even after the physical injuries healed for Jeannot’s family, the emotional pain kept coming as the case worked its way through the justice system.

But Sanchez didn’t let it destroy her or define her, she took the pain and put it into action. She started making gallons of red beans and rice to serve in the community just like her mother did.

“I think it helps us to feel like we're still connected to her in some way,” Sanchez said.

It would be the beginning of an even greater effort in the time since Jeannot’s murder to stop the cycle of crime before it starts.

The Robinson Family

Court documents open a window on the struggles of the Robinson family, both before and after Jeannot was killed.

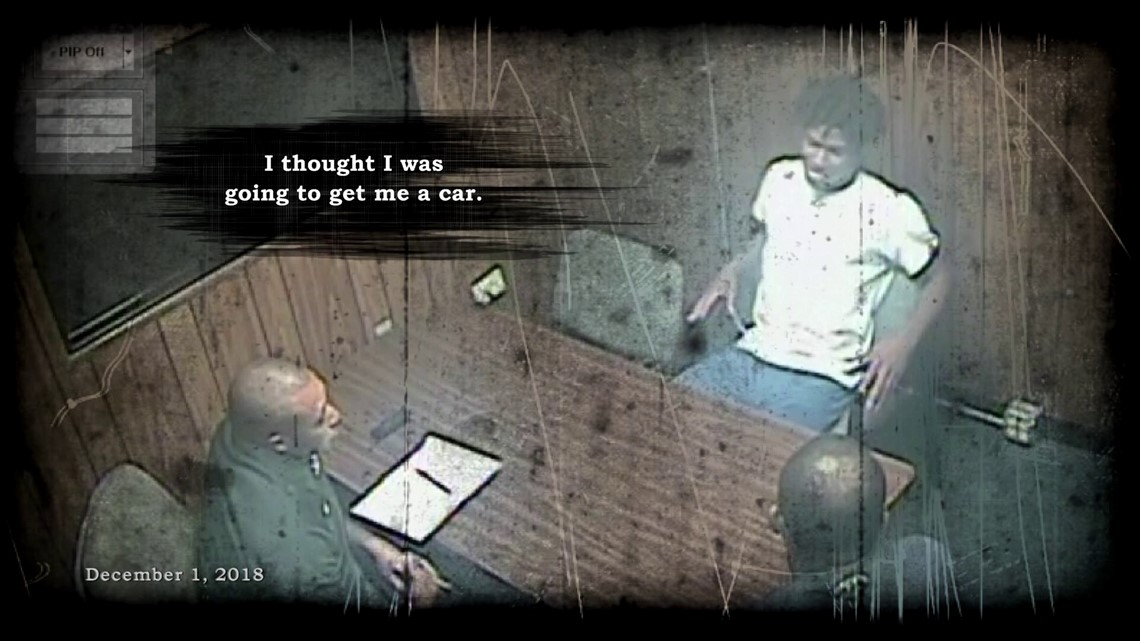

In a video recording captured of the New Orleans Police Department interview room when Jontrell, 17 at the time, sat visibly nervous and upset, he explained to detectives what he and his friends were doing at that time in his life by saying, “I thought I gonna get me a car. We like driving. We know it's bad, but at the same time, we just wanna drive. We'll go to jail and we gonna serve some time, but then we come back out.”

He told police Jeannot’s murder was “a mistake” and that he didn’t mean to hurt anyone, just to steal her car.

Johntrell admitted to police he had been riding around in a stolen white van with an unidentified girl, his brother BoAvanti and cousin Edwin Cotrell. They followed Plessy to Sanchez’s house and when she got out of her vehicle, Jontrell jumped in to steal it. The other three waited in the van nearby.

Court records indicate like Jeannot, Jontrell’s mother, Sherina Robinson was a teenage mom of the two boys and a girl with largely absent father figures. In her apology to the Plessy family after Jeannot’s death, Sherina wrote, “…my sons seeked [sic] guidance from negative environments, they seeked [sic] friendships from the weak and the wicked and had their minds easily manipulated to think being rebellious was a way to behave. I assure you that they were not raised that way.”

Jontrell was a few months away from high school graduation. It’s clear from the recording that was a goal for both him and his mother, one he would ultimately achieve while in state prison.

Sherina declined to be interviewed for this story, saying it was too painful to talk about, but she referred WWL-TV to the Ubuntu Village, an organization that helps mothers and families of children who end up entangled in the juvenile justice system.

“She made note of allowing me to talk about this case that she sympathized and has remorse beyond anyone's imagination about what happened to the victim and what has happened to her kids in this particular case,” said Ernest Johnson, Executive Director of Ubuntu Village. He was present with the Robinsons for many of the court hearings in the Plessy case.

Jontrell is now serving a 30-year prison sentence for manslaughter. Edwin Cottrell, his cousin, is serving 12 years. Jontrell’s brother, BoAvanti pleaded guilty to obstruction of justice and unauthorized use of a motor vehicle. He served six more months from the time of his plea in the juvenile lockup and was required to do community service and graduate high school while on parole over the 18 months after his release.

The Crash

In her apology letter to the Plessy family, Sherina wrote that BoAvanti had been depressed but was making progress by going to counseling, getting good grades and obeying his curfews.

“He didn't have this mindset of just going to carjack and, you know, breaking into cars. He was doing some of the things that was necessary for him to reach his full potential,” Johnson said.

He was working with artists on a project for an upcoming art show at Tulane University about the juvenile justice system.

He wanted to become a rapper.

One night this spring, just days from BoAvanti’s graduation ceremony at G.W. Carver High School, everything changed.

“All I can remember is getting a phone call in the middle of the night and her crying about a situation. You know, it happened two blocks away from her home one week before he was supposed to graduate from high school,” Johnson said about the call he got from Sherina the morning of May 3rd.

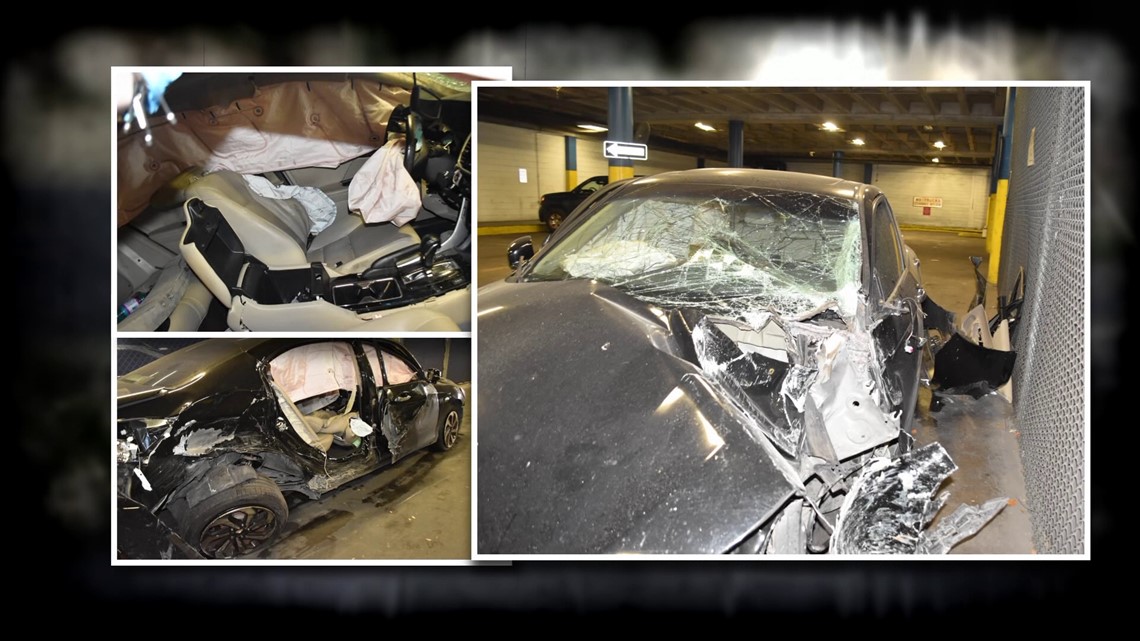

BoAvanti was riding in a Honda Accord with two of his friends.

The NOPD incident report says the driver was traveling at a high rate of speed on Alvar Street and ran a red light, crashing into another car, then jumped the median. The car hit a light pole throwing an unrestrained BoAvanti from the car. The vehicle landed on him and the police report says the two others in the car ran from the scene and left him there.

Sherina went from planning a graduation celebration to planning a funeral.

“She was just torn by thinking that, you know, at the end of the day, because both of her sons were a part of this incident, that at a minimum, just one was going in the right direction and doing what he was supposed to do. But again, that moment changed everything,” Johnson said, referring to the moment BoAvanti decided to get into that car. It, too, was stolen.

His senior picture was placed on top of the closed casket at his funeral, just a day before he was supposed to graduate. Sherina had to walk across the stage to accept the diploma for him.

“She broke down after,” Johnson said.

Sanchez was stunned when she heard about the crash.

“Kristian texted me a picture or texted me the obituary, and I was like, What?” Sanchez continued, “It’s ironic, but I don't find any comfort or peace in that ending for him. I wish, I wish things would have been different for him. I do.”

The police report indicates the parents of one of the boys involved in the crash turned their son into police. Because they are juveniles, it is unclear whether or not they faced criminal charges.

Recipe for Change

When Jontrell Robinson first sat in the police interview room after Jeannot’s death, he told police what happened to her was “a mistake.” He said he didn’t mean to hurt anyone, just steal her car.

Nadia Sanchez wrote about that in the victim impact statement she read to the court during his sentencing, “As much as you want to alleviate some of your guilt by using the word mistake, it was a bad choice.”

Johnson says those choices are made in moments in life that can break a person, not just the one committing the crime, but all of those affected.

At times, Nadia spoke directly to Sherina in court saying, “As much as I hold you responsible for the actions your sons took, I think back to the Friday before my mom died, we were out shopping and had a conversation about anger and forgiveness. We talked about how meaningless it is to hold on to anger. It doesn't change a situation. It doesn't add to your life. It just brings bitterness.”

While Sanchez chose not to let the bitterness break her, the experience of going through the court system changed her.

“It's really hard to witness what we witnessed and experience what we experienced and then be told, like some people might sympathize more with the defendants than with what you're saying. And for that reason, maybe you shouldn't go to trial,” Sanchez continued, “Honestly, a lot of the work that I do was kind of born from that experience.”

She started by making red beans and rice to serve to families in struggling communities after school making the connections her mom used to make. But Sanchez said she realized the need went beyond a hot meal.

“I don't think the criminal justice system is where we have a hard stop and say, well, this person had a really hard life and so we don't think that they should serve this sentence because of that,” Sanchez said the mercy shown to families in need should come first.

She found families needed trauma counseling, other mental health resources and help with everything from utility payments to diapers. Mothers in particular needed better support.

Sanchez started a nonprofit called Love Your Neighbor Nola to help. Two Saturdays a month, she opens up a small office in New Orleans East to allow mothers and families to come “shop” where everything is free.

“You know, a mom lost her kids to jail. I lost my mom forever. And I think the parents that we help right now could end up in either of those scenarios. I mean, anyone at any time could. But the work that I do is really in hopes to get people to access help sooner rather than later,” Sanchez said.

It's her way to help end the cycle of crime before it begins, while Johnson and Ubuntu Village is working toward restoration on the back end with peer-to-peer counseling groups and access to other resources for those tied up in the system.

Sherina Robinson is part of one group and Johnson says it’s helping her and the other mothers who benefit from hearing about her experience with her sons.

“It's making a big difference for the families. It's making to be able to sit down and have those conversations with those families and say, we got to do better,” Johnson said.

The two families will forever be linked and while they both have different feelings about how they got there, they both want to keep anyone else from experiencing it.

► Get breaking news from your neighborhood delivered directly to you by downloading the new FREE WWL-TV News app now in the IOS App Store or Google Play.