The man who beat BP: Thousands tried after the oil spill, but only 1 has succeeded

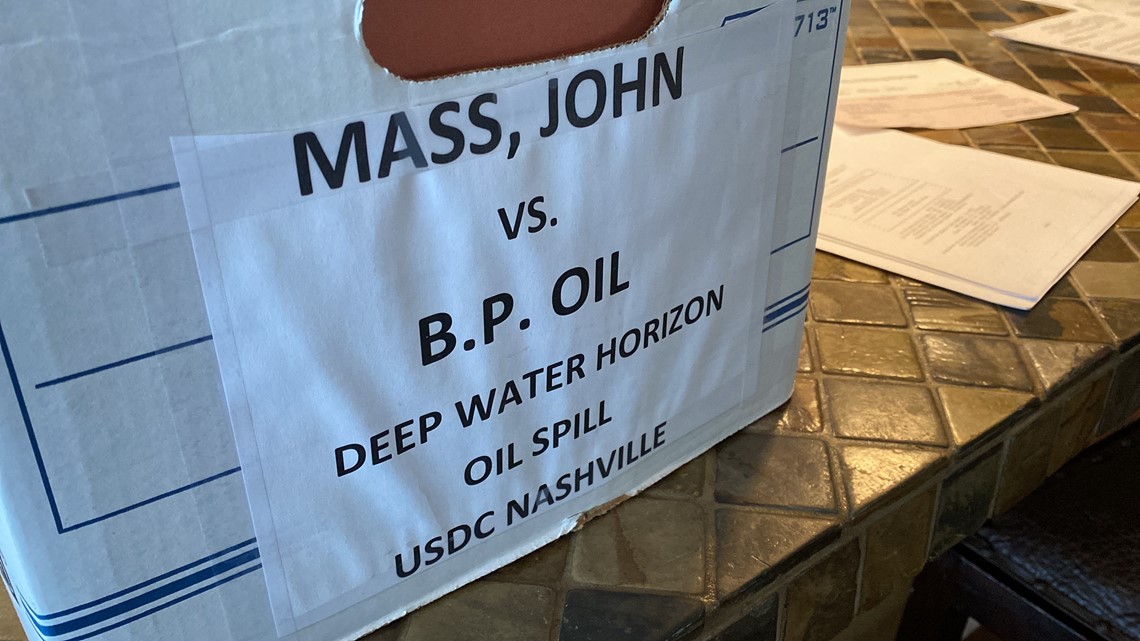

Thousands of residents and workers filed suits seeking medical damages from BP’s oil and cleaning chemicals. John Maas is the only one so far to get a settlement.

John Maas is a rabble-rouser to his core.

He once sued the mayor and police department of Ocean Springs, Miss., alleging he was falsely arrested for taking the mayor’s campaign sign. He accused the local animal shelter there of stealing exotic pets.

When BP hired his charter boat in 2010 to help clean up the its 87-day gusher in the Gulf of Mexico, Maas used a hidden video camera embedded in his sunglasses to record himself complaining about oil damage to his boat and claiming he’d been sprayed with toxic chemicals.

Some of his efforts to fight those in power proved quixotic. But his claims against BP have been a head-scratching, precedent-defying success.

Thousands of coastal residents and oil spill cleanup workers filed lawsuits seeking medical damages caused by exposure to BP’s oil and cleaning chemicals. Maas is the only one to get a settlement to date.

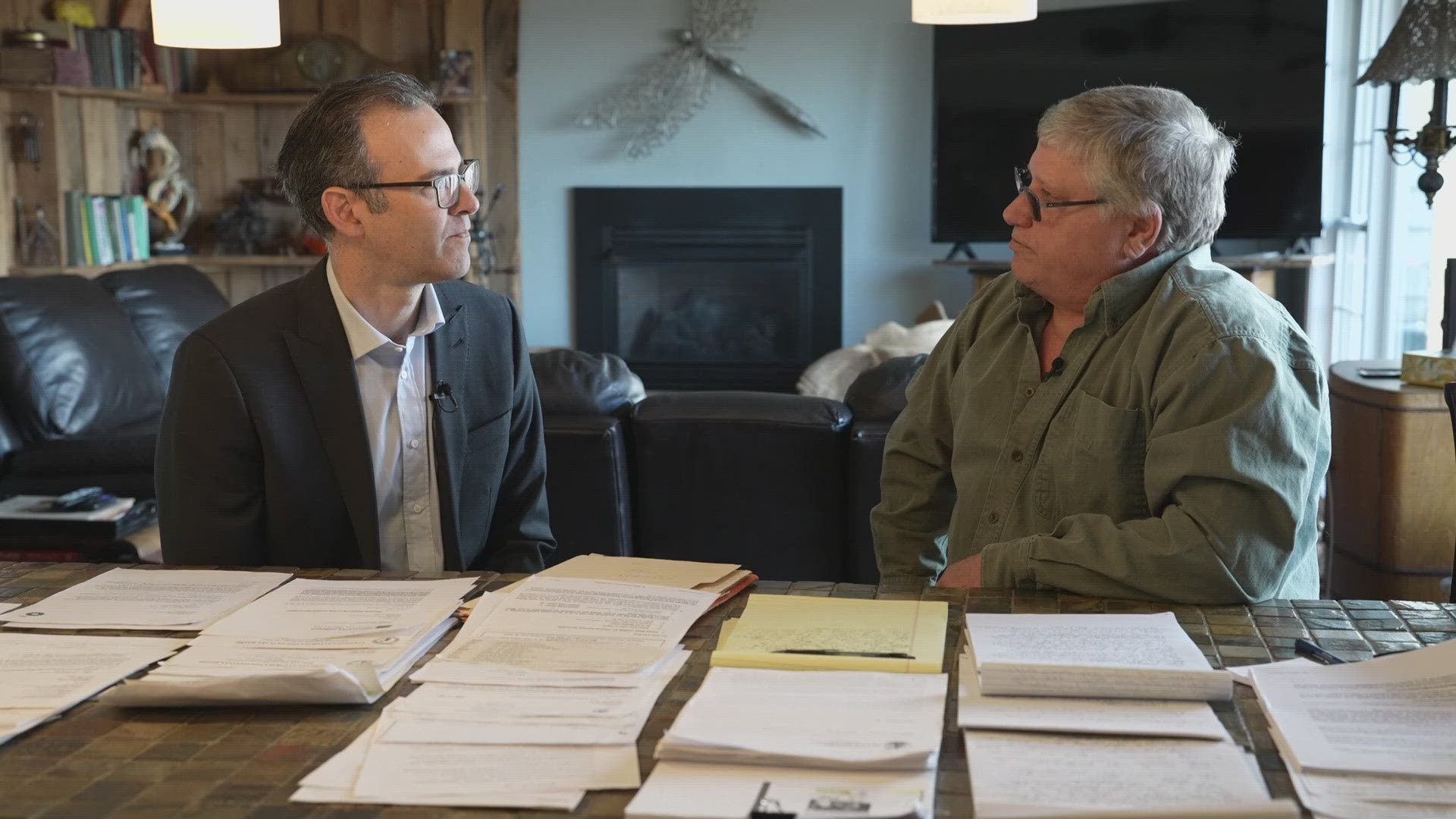

“That's a shame, isn't it?” Maas said when WWL visited his mountain home here. “This story is not about how I won. It's how everybody else lost.”

Outwit, outlast, outplay 'I felt like Jethro Bodine'

Adding to the improbability of Maas’ success: He represented himself, without an attorney, for nine months in New Orleans federal court. A Chicago native who grew up in Hahnville, La., Maas said he was “packing a GED from St. Charles Parish” and, “sheltered by ignorance,” filed hand-written motions that tried the court’s patience.

“I felt like Jethro Bodine in a federal court; Jethro ain't afraid of no judge,” he said, referring to the ignorant-yet-conceited character from “Beverly Hillbillies.”

“I'll throw any motion out there I need to throw, and I'll write them, I'll misspell them, I don't care. They have to liberally construe my motions,” he said, referring to the more lenient standards for pro-se litigants.

A verbal motion he made during a Zoom court hearing in August 2020 likely did more than anything else to tilt the scales in his favor. Maas had moved from the Mississippi coast to the mountains of Tennessee in 2014. After initially challenging Maas’ efforts to transfer his case to the Middle District of Tennessee in Cookeville, Tenn., BP suddenly went along.

Maas’ case raises important legal questions about why he found success in a Tennessee federal court while thousands of others making similar claims have failed in federal courts from Texas to Florida.

Chief Judge Waverly Crenshaw, an appointee of President Barack Obama, denied BP’s efforts to exclude testimony from doctors who said Maas’ chronic respiratory problems were caused by a toxic mix of BP oil and Corexit, a chemical BP had sprayed in record amounts to disperse the oil.

Succeeding where others failed

Crenshaw’s Nashville-based district is in the moderate 6th U.S. Circuit, which covers Tennessee, Kentucky, Ohio and Michigan., Meanwhile, judges in the 5th and 11th Circuits, covering the five Gulf Coast states from Texas to Florida, have repeatedly excluded plaintiffs’ experts.

At a hearing last September, District Judge Ivan Lemelle in New Orleans, who was appointed to the federal bench by President Bill Clinton, excluded a plaintiff’s expert based on established precedent in the 5th Circuit. But he noted the standards were being applied differently in similar toxic-tort cases in the liberal 1st Circuit. He called it a “very ripe issue for the Supreme Court to resolve.”

Attorneys who handled thousands of failed lawsuits against BP blame conservative courts and lawmakers in the oil-producing Gulf Coast states for setting the bar too high to prove that exposure to a specific chemical caused an illness or injury.

“Over the last five years, we've had to dismiss a lot of these cases due to the standards that were being mandated by the 5th and 11th circuits,” said Craig Downs, a Miami-based attorney who filed 4,000 individual medical-claim lawsuits and had at least 2,500 of them dismissed. “They are a very difficult, very high bar…. I think industry has a sway over the court system, unfortunately.”

Maas hired Downs in 2019, and Downs withdrew from his case in 2020 after Maas unleashed a profane tirade over the phone. That was after Maas had fired two previous attorneys, including Houston-based Howard Nations, the plaintiffs’ attorney who filed the most lawsuits against BP. Nations filed more than 5,000 cases and ultimately dropped every one of them.

“We didn't give up,” Nations said. “What we did is we saw by the time we had gone through expert after expert after expert, and so had everybody else, we realized that there was no chance in hell ... on these things.”

Nations said his best epidemiological expert told him the cases were “unwinnable.”

Not supposed to be this way

It wasn’t supposed to be that way. BP agreed to a class-action settlement for medical claims in 2012 and paid 22,800 claimants an average of $3,000. Only 40 of them qualified for $60,700 payments for chronic conditions.

The settlement set up a process for coastal residents and cleanup workers to sue for later-manifested conditions, which BP’s lawyers said in court referred to cancer and other illnesses that don’t show up for years. But in 2014, BP changed its tune. It went back to the court-appointed claims administrator, Matt Garretson, and convinced U.S. District Judge Carl Barbier, another Clinton appointee, that any medical conditions diagnosed as chronic after the date of the settlement would also have to go to the back-end litigation option, or BELO.

Nations said he is waiting for Downs to dismiss all of his remaining BELO cases so he can petition Barbier to reconsider the fairness of the BELO process. He said he wouldn’t put it past BP to have settled the Maas case just so Nations couldn’t argue that BELO cases are unwinnable.

Maas hopes his case can be a model for the remaining plaintiffs, including those who are filing new lawsuits for latent cancers and blood disorders. But Ken Burger, the attorney who handled Maas’ case in Tennessee, thinks it was a one-off.

“I caught (BP’s lawyers) with their pants down, and they're not going to be caught with their pants down again,” Burger said.

End game 'They were taken aback at my crudeness'

Maas said he knew he couldn’t win a so-called toxic-tort case without an experienced attorney. So, he drove to Burger’s law office an hour away, without an appointment.

“I think (BP) thought, ‘We're coming up here to Tennessee and we're probably going to be dealing with Gomer Pyle, Attorney-at-Law, in … Murfreesboro, Tenn.? We're going to be dealing with some yahoo,’” Burger said.

Burger has over 40 years’ experience, mostly in medical malpractice cases. But unlike the big-name maritime lawyers on the coast, he kept his arguments simple. First, he had Maas’ pulmonologist, Dr. Charles Wray, testify that he did a differential diagnosis of Maas and determined exposure to Corexit was the “probable source of his severe pulmonary problems.”

Burger also hired a leading expert, Dr. Veena Antony from the University of Alabama-Birmingham, who testified that Corexit can “produce long-term respiratory issues, such as asthma.”

Judges in coastal states have unanimously accepted BP’s argument that workers should have to prove they were exposed to a specific dose of Corexit to advance their cases to trial. Burger pointed to a case in Knoxville, Tenn., involving exposure to cancer-causing fly ash to argue that specific doses were unnecessary to prove causation.

Crenshaw agreed and dismissed BP’s motion for summary judgment in December 2021. “BP’s argument fails,” Crenshaw wrote.

That decision paved the way for the case to go to trial in the single-courtroom federal building in Cookeville, Tenn. It never made it that far. BP came to the negotiating table in February 2022, and right into Maas’ wheelhouse.

“They were taken aback at my crudeness,” Maas said. “And I worked on them for eight or nine hours that day to get the settlement.”

In typical rabble-rouser fashion, Maas also shared his full settlement documents with WWL, in direct defiance of a confidentiality agreement and Burger’s advice. The records show BP paid him $110,000.

“BP hasn't told me the truth about a damned thing,” he said. “They think I want to abide by their confidential settlement agreement? You got to be f------ kidding!”