The U.S. Department of Justice is not in the habit of sticking its nose in backroads Louisiana custody battles.

But on May 5, 1999, the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Louisiana issued a grand jury subpoena to the Livingston Parish Clerk of Court's Office.

Written by then-U.S. Attorney L.J. Hymel, the order demanded “any and all records” in the clerk’s possession on a pair of family law cases — a divorce and a related child welfare proceeding that included searing allegations of abuse against a 5-year-old boy. Combined, they were the “Nicholson case."

An FBI task force was waiting for the documents.

Their target was Judge Jefferson Hughes III, according to a document Hymel later filed in an unrelated case. The Advocate obtained that document recently and verified the claims Hymel made in it through hundreds of other records — some of them decades old — from the state Supreme Court, state 1st Circuit Court of Appeal, Livingston Parish district court and juvenile files, along with numerous interviews.

The FBI investigation would continue for five years. When it began, Hughes was halfway through a 14-year stretch as a state judge in Livingston Parish. He is now a Louisiana Supreme Court justice. And yet, over the past two decades, the probe into Hughes does not appear to have crept into public sight.

The investigation into Hughes’ handling of the Austin Nicholson matter was prompted by an explosive complaint from the child’s grandmother. Hughes, she alleged, had refused to acknowledge a blatant conflict of interest, even as he fought tooth and nail to control the child’s custody case.

At the time, the grandmother claimed, Hughes was in a romantic relationship with Berkley Durbin, who represented the 5-year-old boy’s mother, as well as the mother’s new husband on his criminal charge for hurting the boy. For a time, Hughes oversaw that case as well.

It appears the feds were trying to understand how the relationship affected Hughes’ impartiality — and if it did, whether it represented a federal crime. It’s not clear whether they ever came to a conclusion on the first question, but on the second, they opted not to file a charge.

Experts say Hughes appears to have violated judicial canons by failing to recuse himself — a violation he may have compounded by taking extraordinary steps on behalf of his girlfriend’s clients. Hughes’ actions also prompted a separate inquiry by the Supreme Court’s judicial enforcement arm, which likewise produced no public accounting of Hughes’ actions.

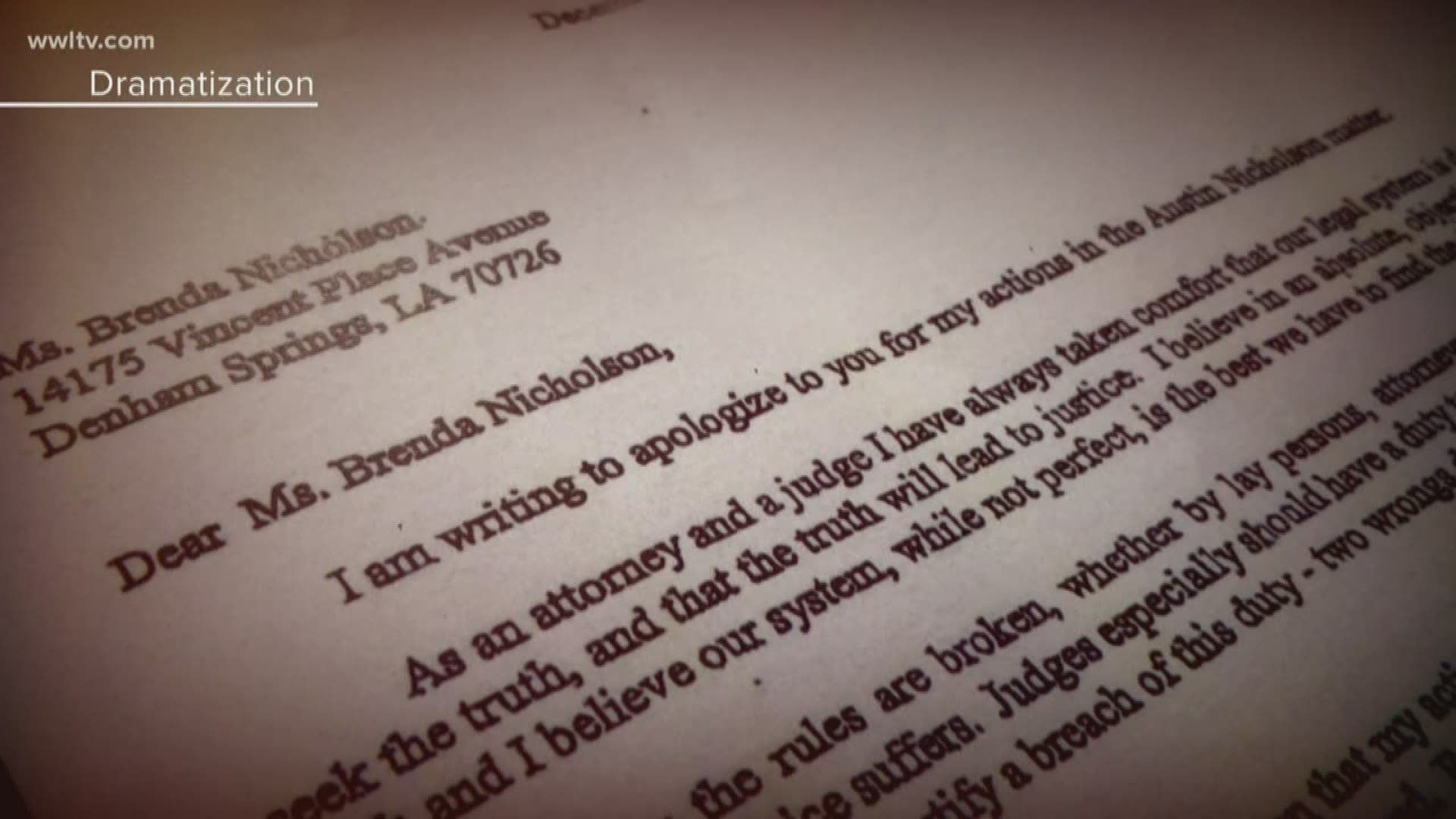

The grandmother, Brenda Nicholson, said she was never told what happened to her complaint. But in late 2004, she received a letter. Hughes had scribbled his signature beneath a four-paragraph, typewritten note on his personal letterhead.

She kept it in a weathered briefcase, alongside photos of her grandson, Austin Nicholson, and his father, Rodney, her son.

“I am writing to apologize to you for my actions,” Hughes’ letter began. “I have come to the conclusion that my actions were inimical to the pursuit of the truth and that, because of my actions, justice suffered. For this I am deeply remorseful.”

The judge’s missive never specified what actions he regretted.

Signs of abuse

The case began with a trailer-home bathtub, burning flesh, a hospital visit and a restraining order filed in April 1998 by Rodney Nicholson.

His estranged wife, Kristin, had a new boyfriend and soon-to-be husband, Marc Fuselier, a roofer with a short fuse, a long rap sheet and a unicorn tattoo on one shoulder. Austin Nicholson, now 26, remembers that he argued with Fuselier about whether his bathwater was too hot.

“He picked me up and put me in the water, and one hand was on my neck, the other was on my chest,” Austin told The Advocate. “I was kicking and screaming to get out.”

Story continues under photo

Second-degree burns covered the boy’s body. The District Attorney’s Office wrote that a forensic pediatric expert determined his injuries were “definitive for physical abuse.”

It wasn’t the only time he suffered. Austin said Fuselier sometimes forced him to drink dish soap mixed with cough syrup.

In a recent interview outside his home in Walker, Fuselier denied ever hurting Austin. He said the burns were an accident, that the boy drew water that was too hot and burned himself.

But state social workers found other signs of abuse. And a few days before the scalding water incident, Austin told them that Fuselier paddled him, according to their notes.

After the bathtub episode, Rodney Nicholson rushed back from Mississippi, where he had been living. Rodney Nicholson’s parents and Austin’s grandparents, Brenda and Doyle, lived in Denham Springs about a half-mile from Austin's mother and Fuselier. Austin lived most of his young life there.

Hughes was assigned the case and granted temporary custody to Rodney Nicholson, with orders for Fuselier to stay away. For about a year, until March 1999, the boy remained with his grandparents and his father in Brenda and Doyle’s house.

“That’s where most of my fondest memories are from,” Austin said.

The Fuseliers’ lawyer, Durbin, had filed a motion to ensure that Hughes would oversee the divorce petition she’d recently filed for Kristin in tandem with the restraining order against Marc Fuselier. Experts say that’s not unusual.

But court records show Hughes started to issue rulings more favorable to the mother, now Kristin Nicholson Fuselier. Hughes first granted her daytime visitation, then unsupervised visitation at her home. Now she was pushing to win back custody of Austin, even though her new husband still faced prosecution for hurting him.

'You can't possibly be impartial'

Hughes set things in motion. That’s when the Nicholson family confronted the judge with a stunning allegation: that he was in the tank over a romantic relationship with Durbin.

A 1999 motion to recuse hinted at the conflict, saying Hughes was biased or prejudiced toward Durbin or the Fuseliers. The motion was vague: It said the reason for the alleged bias was “delicate and personal” but that Hughes had been confronted with it. And a judicial complaint the Department of Social Services filed that same year alleged that Hughes was demonstrating a strong bias toward Durbin’s clients, while pointing out the relationship between the two.

Hughes and Durbin were both unmarried. Neither one responded to numerous messages from The Advocate.

But others who were involved in the case from all sides said their relationship was well-known.

Scott Perrilloux, who was first elected in 1996 as 21st Judicial District attorney, said in a recent interview that he was aware of it.

“Yeah, I remember them dating. I know them on a personal level,” Perrilloux said. “I don’t think it was a secret. Yes, I knew. I don’t remember the dates.”

Perrilloux said he wasn't aware that Durbin had practiced before Hughes at the time.

Brenda Nicholson, too, said it was “common knowledge.”

“We knew things were not going right,” she said. “We went to the judge and said, 'We know you’re dating Berkley Durbin.' ... We were face to face with him. I said, ‘You can’t possibly be impartial about this.’ ”

Marc Fuselier said his lawyer mentioned it during the long hours he spent in her office. But he downplayed its significance.

“It wasn’t like they were in love with each other,” Fuselier said. “Berkley ... you know, said they were just good friends and they were ‘friends with benefits.’ That’s what she said.”

When he was confronted at the time, Hughes was dismissive.

“ 'Just no. I am not stepping down,’ ” Brenda Nicholson recalled him saying.

Court records show that Hughes ruled on his own alleged conflict, and found none, rather than bring in another judge to hear the motion. The public court record is silent on whether Hughes denied the relationship or just believed it didn’t constitute a legal conflict.

A lawyer for the Nicholsons argued to no avail that Hughes had blatantly ignored the rules regulating judges in Louisiana.

“I remember feeling as though we weren’t going to get a fair shake,” said the attorney, Glen Smith, who has since been disbarred. “And the fact that he didn’t recuse himself — I do recall being a little surprised.”

Custody battle

A day after the Nicholson family asked Hughes to step off the case, the judge granted custody of Austin to Kristin Fuselier.

Hours before Austin’s mother was set to pick him up at Seventh Ward Elementary, Brenda and Rodney Nicholson took him away to Mississippi.

Story continues under photo

Hughes quickly signed arrest warrants for both father and grandmother for defying his custody order and ordered both held without bail until the boy’s safe return.

Brenda Nicholson landed in jail for 11 days.

Hughes’ decision to return the boy to his mother went squarely against the wishes of Louisiana child welfare authorities, who saw abuse waiting to happen. They stepped in with a fresh argument for keeping Austin in state custody.

In May 1999, social workers wrote that “the child gets in a fetal position at the suggestion of contact and returning to an environment where Marc Fuselier is also living.”

“I really didn’t feel 100% safe there with my mom and Marc,” Austin Nicholson said recently. “I felt like she overlooked everything I said because I was younger and he was an adult and could make it sound believable.”

By the time of the custody hearing, overseen by Hughes, Durbin was no longer the lawyer of record. She’d officially left the case in August 1998, court documents show.

But Durbin never strayed far — before, during or after Hughes’ custody decision and his campaign to enforce it. Her name continued to pop up on Marc Fuselier’s criminal case, and later in the custody case as Austin’s fate continued to unfold.

Hughes’ custody decision set off a flurry of recriminations.

'He didn't have the authority'

While Austin waited in foster care in Mississippi, Hughes sought to wrest the child away and return him to his mother.

In a court filing, Hughes excoriated child welfare officials in two states, accusing them of using deceit to dodge his order to return the child. And when a Mississippi judge rebuffed him, Hughes tried to pull rank with the Mississippi Supreme Court and that state's attorney general.

Sherry Watters, who has retired from a three-decade career as a state child welfare attorney, was part of a legal challenge to Hughes’ transfer order. She declined to discuss the case or the allegations against Hughes in detail, but she easily recalled it 20 years later.

“To my recollection, he just had a personal interest in the parties and stepped over another judge’s order and claimed jurisdiction he didn’t have to do things he didn’t have the authority to do,” she said.

Another attorney from the case also remembered how Hughes reacted when the judge saw signs outside the courthouse demanding justice for Austin.

“He lost his temper and he completely lost his cool out in the parking lot,” said James Maughan, who represented Rodney Nicholson in 1999. “And he went over there and started yelling and grabbed the paper (sign) and ripped it in half.”

A Mississippi judge ordered that the boy be kept there until he could be placed with Louisiana child welfare workers.

The custody battle was coming to a head in spring 1999 when an appeals court granted a stay sought by Louisiana’s child welfare agency. The court had also asked Hughes to explain his actions. The federal subpoena showed up the next day.

Another judge, now deceased, took over the custody case.

Fuselier said the feds “took Judge Hughes off the case because him and Berkley were seeing each other.” But court documents that spell out Hughes’ departure are not present in the case file The Advocate reviewed. The motion to recuse Hughes is also missing from the related criminal and civil records in Livingston Parish that the clerk’s office provided to the newspaper.

The Advocate was able to review the motion because another attorney kept a copy.

The court’s judicial administrator, Sara Brumfield, said she had no immediate answer for the absence in court records of the original motion.

'Trying to cover his tracks'

In 2004, around the time the FBI investigation quietly ended, Hughes was elected to the appeals court. Soon afterward, Brenda Nicholson received the letter.

“He wasn’t really apologizing,” she said. “He knew what he had done, and it was just totally wrong. He threatened everyone. I think a lot of what Jeff Hughes did after a certain time was trying to cover his tracks.”

Hughes won a seat on the Supreme Court in 2012, running as a Republican, and was reelected in 2018 without opposition. The sordid episode did not surface.

A Denham Springs native and once a Democrat, Hughes touted his conservative bona fides during his Supreme Court campaign as “pro-life, pro-gun and pro-traditional marriage.”

But he has never been popular among oil and gas interests; a trial lawyer-funded group called Citizens for Clean Water and Land PAC helped boost his campaign. Many oil companies supported his Democratic opponent, fearing Hughes would uphold “legacy lawsuits” against their companies for polluting private land.

In 2016, Hughes sued four fellow Supreme Court justices after they ruled that he could not fairly hear two legacy lawsuit cases because of his campaign contributions and ordered him recused. A federal judge dismissed Hughes’ lawsuit.

The allegations about Hughes’ conduct in the Nicholson case are described in a partially redacted public record that’s part of an unrelated lawsuit. Hymel, the former U.S. attorney, outlined his investigation in a 2011 motion buried in a case file over a deadly fertilizer plant explosion a decade earlier.

Hymel represented CF Industries Inc., whose Donaldsonville plant exploded, in a long-running civil case. Hughes was part of a three-justice panel set to hear an appeal.

Hymel submitted a motion to recuse Hughes, asking that it remain under seal. Instead, the 1st Circuit ordered that a version with few redactions be included in the public file.

In that record, Hymel described the grand jury probe and included an affidavit from Brenda Nicholson and a copy of Hughes’ apology letter. The filing about Hughes is available only in the Supreme Court’s case file.

In his motion, Hymel took full credit for the decision to turn Hughes over the federal spit, but he said he had no personal animus toward the judge.

“Numerous witnesses in Livingston Parish were interviewed by the FBI and the U.S. Attorney’s office, including Judge Hughes, and witnesses and other evidence were presented to the federal grand jury in Baton Rouge,” Hymel wrote in his motion. “The allegations pertained to improper conduct by Judge Hughes while he was a district court judge, including an improper relationship.”

In an affidavit, Hymel wrote that the federal investigation ended under his successor, with a finding that Hughes had committed no federal crimes.

The recusal motion was denied. Hughes went on to write the 1st Circuit’s 2012 judgment in favor of Hymel’s opponent.

When reporters visited Hymel’s home, he declined to discuss the case.

Lewis Unglesby, who represented Hughes during the FBI investigation, said Hymel had “no right” to file such a motion after an Advocate reporter described it to him. He declined to comment further.

'Forgiving isn't forgetting'

After all the fighting about who should raise Austin, the boy never returned to either parent. He bounced around foster homes before his father's sister Milinda Fraley returned from Germany and took him in. They moved a few years later to Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

Austin said his aunt “gave him the life and the love I needed.” He’s now a 26-year-old Army veteran, still in Iowa, with a daughter of his own.

“He had a lot of anger issues. He just wanted to be at our house. He wanted to be with us. We took care of him the most, and he was ripped out of there,” Brenda Nicholson said. “You could tell he was angry, just kept pushing it in, pushing it in.”

In 2013, Rodney Nicholson died at 43 of sepsis from an apparent drug overdose, after being sick for a while, family members said.

“He lived with the guilt and remorse of losing Austin,” Brenda Nicholson said. “His body couldn’t take it. ... He drank a lot. He relived it over daily.”

Austin said his father’s death devastated him. Rodney Nicholson had attended his boot camp graduation and the two liked to trek together through the woods.

A few months after the federal grand jury issued its first subpoenas, Marc Fuselier went to court over the abuse charge. He pleaded no contest in 1999, and Judge Robert Morrison III handed him a suspended five-year sentence with supervised probation. Fuselier said it’s a decision he regrets.

Fuselier said Hughes advised him privately to take the no-contest plea because “with all the crap that was going on at the time, he said it could go either way.” Durbin was still listed as his attorney.

Fuselier said during the hearing that he accepted responsibility for “what happened” to Austin, but he referred to it as “the accident.”

Austin Nicholson sees it differently.

“I forgave him a long time ago,” he said. “Forgiving isn’t forgetting.”

Legal experts told The Advocate that Hughes’ actions appear to violate well-understood norms. A judge carrying on a romantic relationship with counsel on a case over which he exercises control should recuse himself, and it isn’t a close call, said Deborah Rhode, director of the Center on the Legal Profession at Stanford Law School.

“It’s a classic conflict of interest, an obvious source of bias,” Rhode said.

Stephen Gillers, a law professor at New York University who specializes in legal and judicial ethics, had a similar take. He said a judge is obligated to recuse himself in such a case, or to reveal the relationship to the litigants.

If the judge does the latter, Gillers suggested, he may continue to preside only if both parties waive their concerns.

Whether Hughes would have made the same decisions in the case absent the relationship with Durbin is irrelevant in terms of judicial ethics, Gillers said.

“It doesn’t matter. It’s like when officials are bribed,” he said. “They say, ‘I would have done the same thing even if I weren’t bribed.’ In fact, that’s something we can never know for sure.”

Louisiana’s Judicial Code of Conduct says judges “shall avoid impropriety and the appearance of impropriety.” It also says judges “shall not allow family, social, political or other relationships to influence judicial conduct or judgment.”

Austin Nicholson doesn’t recall much of the chaos of those times. What he does remember is that he spent enough time at the Livingston Parish courthouse that he could still picture his favorite tree there, with branches that hung low enough for him to climb.

A reporter with a lingering question texted Austin last week.

“Did anyone ever apologize to you?”

Four minutes later, he responded.

“No,” Austin wrote. “Unfortunately no one did.”

Staff writers Faimon Roberts and Sam Karlin contributed to this report.