NEW ORLEANS — At first glance, the police body camera seems to capture a New Orleans police officer handling a routine fender bender. According to federal authorities, it turns out to be something far more devious, but the clues are well-hidden.

The video from June 6, 2017 shows officer Debra Spriggins as she pulls up to the scene at Downman Road and Chef Menteur Highway.

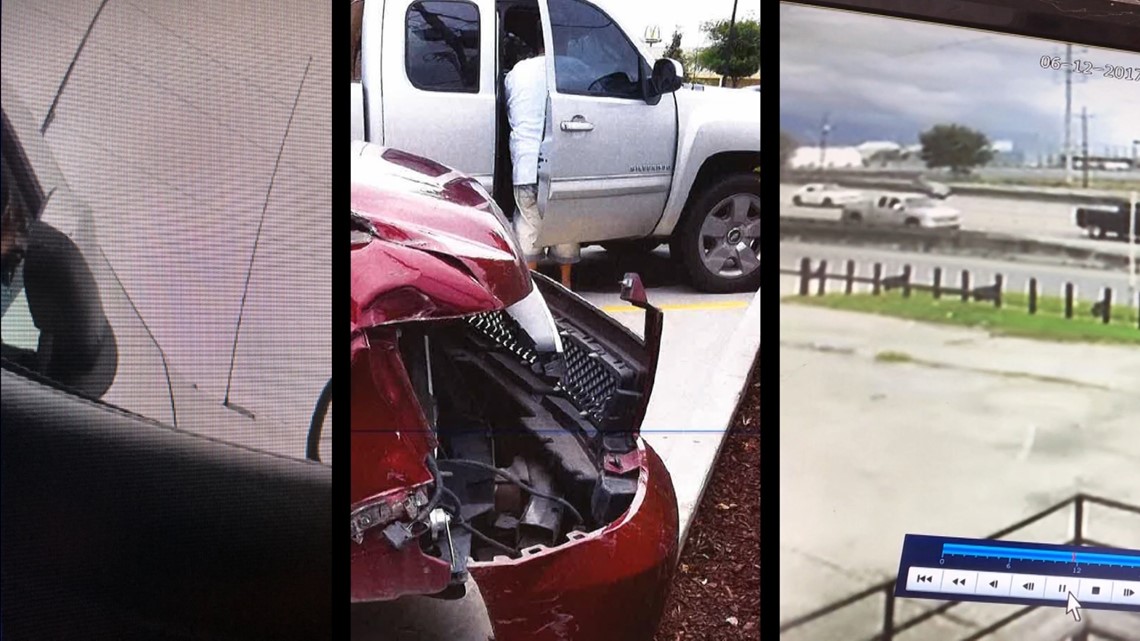

From her perspective, we see a Chevrolet Avalanche parked on the shoulder with a crushed left front fender. Behind it is an 18-wheeler, a refrigerated truck carrying frozen chicken.

Before Spriggins gets out of her police cruiser, a man walks up to her window and begins telling her what happened.

“She's scared,” he says, referring to the driver of the Avalanche. “She's terrified. She did not hit him.”

The man goes on to describe how the big rig hit the Avalanche, which was carrying four women from Houma. He leaves his name and phone number before running across the street.

When Spriggins gets out of her car to assess the scene, Lucinda Thomas, 63, emerges from the driver’s seat of the Avalanche. Her account matches the seemingly independent witness.

“I don't know. It happened so fast. He hit the side of the truck and started pushing me over and he never even stopped,” she tells the officer.

The driver of the 18-wheeler disputes her account.

“I saw her behind me. And another silver truck behind her,” he tells Spriggins. “I was in the right-hand lane. I don’t know if she tried to pass me or tried to force me over or what.”

About 10 minutes later, as if on cue, that silver truck, a Chevy Silverado, pulls up to the scene. It’s the vehicle the tractor-trailer driver said he saw driving behind the Avalanche.

In the body cam video, the passenger in the Silverado can be heard, but not seen. Pulling up to Spriggins as she is seated in her police car the man says, “I got something that'll trip your head out in a minute. You want water or Gatorade?”

"Water is fine,” Spriggins responds.

Three minutes later, the Silverado returns. The passenger can be seen handed a bottle of water to the officer through the window.

“Thank you so much. Thank you, baby,” Spriggins says.

“Now listen, I gotta tell you the truth,” the man begins.

From there, the passenger excitedly explains the accident as he saw it.

“I saw what happened,” he says. “The lady was straight. We behind her. And he cut across the median…He hit her."

By the time the officer is done assessing the scene and taking everyone’s driver’s license information, she emerges from her police car and delivers the words Thomas has been waiting for.

“I'm going to get you all of his information, ma'am. He's going to be at fault,” Spriggins says.

Over the next two years, Thomas filed a lawsuit, underwent surgery and was paid a settlement. Her passengers – Mary Wade, Judy Williams and Dashontae Young – also got paid.

But what appeared at first glance to be a routine accident, is anything but, according to federal authorities. The U.S. Attorney's office says the entire accident was a scheme, an elaborate con job.

This video is now one of many pieces of evidence the feds have obtained to reveal what the trucking industry has complained about for several years: staged accidents at the hands of a loosely organized ring of scam artists.

It works like this: pack a car with people, side-swipe an 18-wheeler, then plant witnesses at the scene to blame the truck driver. Later, file a lawsuit claiming serious injuries.

But in the accident on June 16, 2017, the tables have been turned. A federal indictment handed up in October charges Thomas and her three passengers with conspiracy for staging the accident and wire fraud for collecting settlement checks.

A fifth defendant is Damian Labeaud. He’s identified as the Silverado passenger who claimed to be an independent witness. In the indictment, he’s accused of organizing the high-stakes hustle.

Labeaud is well-known to law enforcement authorities. After serving a 7-year prison sentence for manslaughter in the 1990s, Labeaud collected settlements in five accident lawsuits over eight years, then popped up as a witness in several others.

Labeaud was identified as the “witness” in this accident by the law firm representing the trucking company, Galloway Johnson.

The law firm, suspecting the same scheme that has plagued truck drivers in New Orleans for years, hired a voice analysis expert to determine that the distinctive high-pitched voice in the body cam video belonged to Labeaud.

“The gentleman who sounds like Mike Tyson is, in fact, Damian Labeaud, according to the expert's report,” WWL-TV legal analyst Chick Foret said.

In the indictment, the U.S. Attorney’s office alleges that Labeaud actually drove the women's car, lined up the accident attorney and – revealed through phone records – talked to the attorney a short time before the collision.

That lawyer has been identified through phone records as Daniel Patrick Keating, referred to in the indictment as "Attorney A."

“It's almost like 'Sting,' the movie, where they've got a con game that they're playing,” Foret said.

“Six days after the accident now under indictment, Labeaud was connected to an almost identical 18-wheeler accident. This second wreck also took place on Chef Menteur, only it was exposed as a fraud almost immediately by a video camera mounted on the truck.

After trucking company defense attorney Doug Williams revealed the video, the three plaintiffs in that case dropped their suit and their attorney withdrew from the case.

The attorney? Daniel Patrick Keating.

A lawyer representing Keating declined comment, as did attorneys for Labeaud and the four women indicted along with him.

“Those cameras right there saved between $150,000 and $250,000 just by capturing the fraud and us not having to go and defend it,” Williams said.

Williams shared his information with the law firm representing the truck company in the first accident, Galloway Johnson.

As the lawyers studied the evidence in the two cases, they connected the dots. Damian Labeaud appears in each. The Silverado appears in each. Keating is a central figure in each.

“They are the ones we run into time and time and time again in New Orleans. And they have a good dog-and-pony show,” Doug Williams said.

In more than 20 other New Orleans truck accident lawsuits flagged as suspicious, defense attorneys used similar tactics to fight back: obtaining videos, phone records, social media posts, then cross-referencing the same names across multiple cases. In eight of those cases, federal judges have halted the suits due to “the ongoing criminal investigation.”

Now let's watch segments of the video again. Seemingly innocuous details become very revealing.

That first witness who approached the officer. As quickly as he appears, he's gone. The name and number he gave: bogus. Yet he is included in the police report.

In the video, Thomas emerges from the car without any difficulty and never complains about being in pain. Yet Keating claimed her injuries were so severe, his first demand for damages was for $1 million.

“She looks grandmotherly. She looks like she is totally legit,” Foret said. “But now when you look at her again, try to digest the fact that she wants a million dollars for her injuries.”

In the video, Labeaud seems to ingratiate himself with Officer Spriggins, first by bringing her water, then by dropping names of people they both know.

“In New Orleans, I would call that the ‘Where y'at, baby moment.’ ” Foret said.

Another key piece of evidence emerged later as Galloway Johnson contested the lawsuit in civil court.

A photograph of the wrecked Avalanche taken a few hours after the collision parked in a Cane’s chicken parking lot includes the Silverado in the background.

Leaning into the Silverado is Damian Labeaud.

“This is a rare commodity. Very rarely do you see a body cam video of the crime in progress,” Foret said.

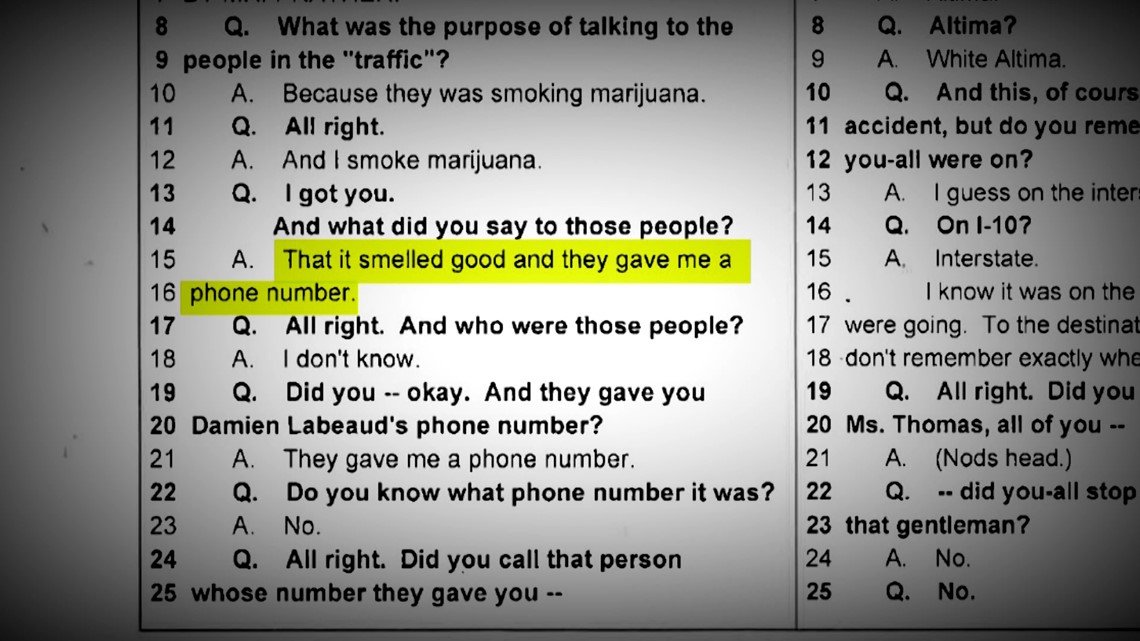

Before the FBI saw any of the evidence, Lucinda Thomas and her passengers were grilled in depositions. Specifically, they asked about phone records showing contacts between them, Labeaud and Keating, including calls and texts before the accident.

Their explanation?

Prior to Labeaud showing up as a witness, before the wreck even, the women said under oath that they drove beside a car with men smoking marijuana. Interested, they said they obtained a phone number from the men, a number that turned out to be Labeaud's.

“There's no judge or jury that's going to accept that explanation as being reasonable,” Foret said. “The law firm involved in this, representing the trucking company, Galloway Johnson, did a masterful job in putting all of this together.”

Reams of evidence uncovered by attorneys for trucking companies is now in the hands of federal authorities. But the impact of the case could go way beyond the trucking industry.

State officials say Louisiana drivers pay an estimated 600-hundred dollars a year in extra insurance because of fraud.

“This type of fraud affects everybody that carries insurance,” Goyeneche said.

Goyeneche said advances in technology, such as police body cameras and dash cams mounted on 18-wheelers, are helping the crackdown on this difficult-to-prove scam.

“Now the mindset is, in large part because of the technology, we can prove a fraud. Let's refer it law enforcement,” Goyeneche said. “A picture's worth a thousand words and having photographic proof is very compelling.”

This is part four of "Highway Robbery," an investigative series by Mike Perlstein. Watch parts one, two and three.

► Get breaking news from your neighborhood delivered directly to you by downloading the new FREE WWL-TV News app now in the IOS App Store or Google Play.