When Evan Howington and his attorney came to New Orleans in mid-2014 to meet with some government agents, they were armed with some of the most damning evidence imaginable of environmental crimes in the Gulf of Mexico.

Howington knew that his career working offshore was probably over. He was exposing the blatant dumping of oil and chemicals by his supervisors on an oil rig, including the top representative on the rig for a Houston-based oil company, Walter Oil & Gas Corp.

“I thought, ‘I have to speak up. If I let this go, then I’m the same type of people they are: criminals,’ ” Howington said.

Indeed, after a federal investigation was completed a year and a half later, Walter Oil & Gas pleaded guilty to a felony.

But it wasn’t at all what Howington and his attorney, Tommy Servos, had expected. When the charges were announced in October 2015, they weren’t even sure if it was their case because the allegations seemed so limited compared with the evidence they had provided.

“It's a slap in the face, not just to me but to anyone who wants to come forward,” said Howington, who has filed an administrative claim against the prosecutor involved for allegedly letting the company and its contractors off the hook.

In a plea bargain like the one the government negotiated with Walter Oil & Gas, it isn’t unusual for prosecutors to limit the charges in exchange for a guilty plea. But letting oil companies off with “a slap on the wrist,” as Howington called it, is a scenario that has become all too common in the Gulf, according to environmental watchdogs and other whistleblowers.

The government promised to crack down on environmental crimes in the wake of the devastating BP oil spill in 2010. And at first, it appeared to be fulfilling that pledge. The fines against BP set the record as the largest criminal penalty in U.S. history: $4.5 billion.

But since then, the federal government has eased the pressure. Congress failed to put into effect the tougher offshore oil and gas production regulations that were recommended after the BP spill; a ballyhooed training center for government inspectors was scrapped; the Interior Department’s environmental enforcement division was understaffed and couldn’t perform its basic oversight duties; and when companies were caught violating environmental laws, prosecutors were unwilling to reward whistleblowers.

Still, there was reason to believe the government would be more aggressive with Howington’s case. Rarely have the authorities had so much to work with as they did with his video evidence.

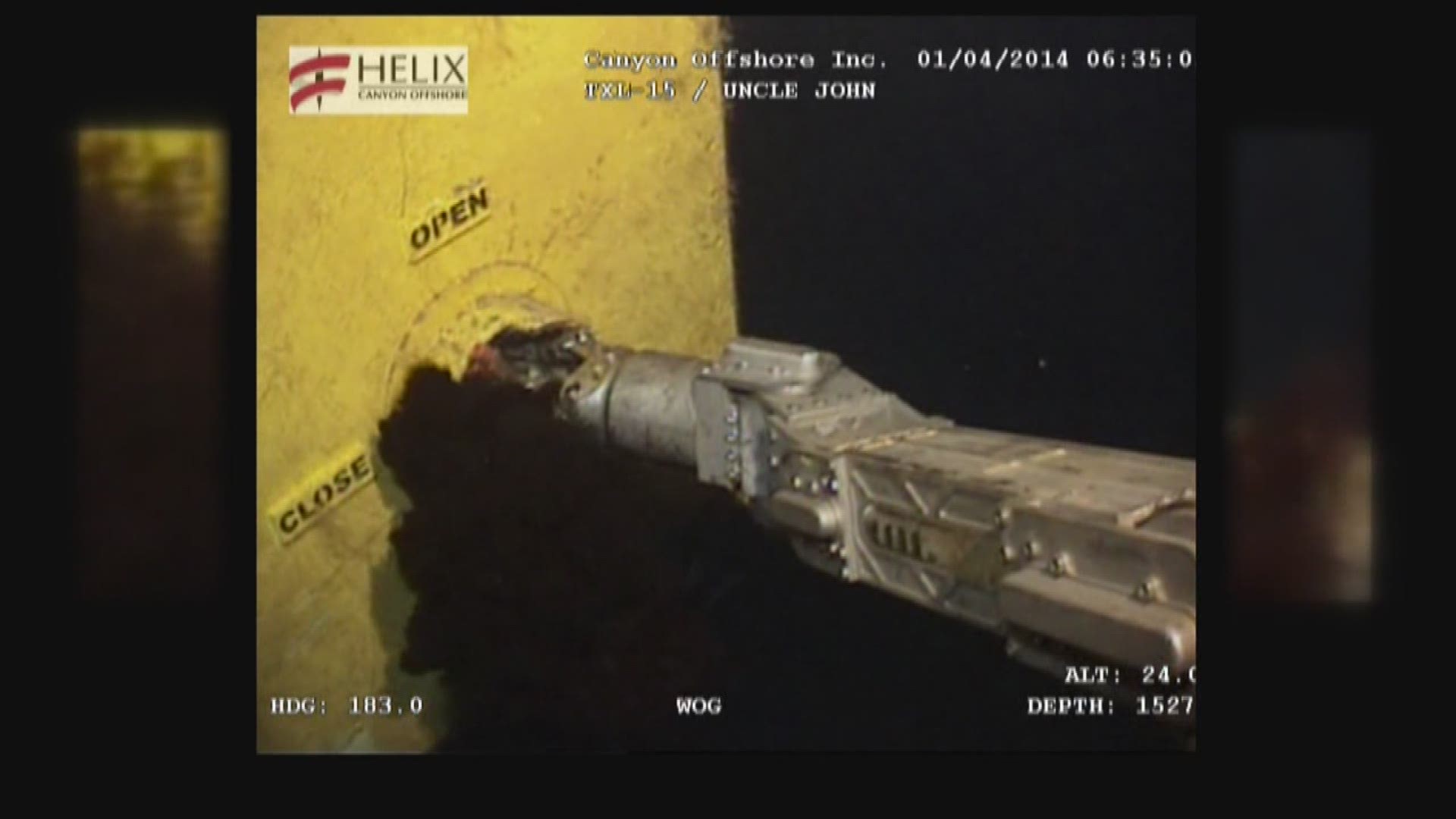

Howington and Servos brought the feds copies of crystal-clear video showing chemicals and what looked like oil gushing out of a pipe 1,500 feet below the surface of the Gulf on April 1, 2014. It was recorded by a camera mounted on a remotely operated vehicle, an unmanned submarine Howington and other rig workers controlled from a floating oil rig.

And it showed a robot arm manipulated very deliberately to open a valve and let an illegal discharge gush out for nearly 90 minutes.

“It’s a bulletproof case,” Servos said.

Howington used his cellphone to record his supervisors and fellow workers talking about the incident for more than 20 minutes. They acknowledged that the discharge was likely oil but discussed how they should say it was other chemicals. They acknowledged that it was illegal. They described how they could cover up the discharge altogether.

Howington also took pictures of the log books where the incident was recorded simply as “continuing to monitor pressure.”

“Yeah, I know how to word that (expletive),” said the top Walter Oil & Gas representative on the rig, David Thibodaux, as heard in the cellphone video.

&

And finally, Howington presented agents from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality and a prosecutor from the U.S. Attorney’s Office with photos and video of hydraulic oil spilling on the rig floor. Howington claimed it flowed into the Gulf each day for the 24 days he was on the rig and that his attempts to stop it were ignored.

The prosecutor in that meeting was Matthew Coman, and Howington said Coman sounded eager to pursue the case.

“He prosecuted the former mayor of New Orleans and he was willing to go out there and take on tough cases, and I thought, ‘I’m in good hands,’ ” Howington said, referring to the government's successful prosecution of former Mayor Ray Nagin.

But then, Coman left the U.S. Attorney’s Office for a private law firm. A different assistant U.S. attorney, Jon Maestri, took over the case. Howington said Maestri never met with him before charging the company with a single count of failing to report a discharge.

“Most of all I was disappointed because I did all of this; I gave it to you,” Howington said. “Here, it’s your job to take care of this. And I felt they dropped the ball.”

Typically, the federal government charges companies, not individuals, with environmental crimes for pollution on oil rigs. But charging individuals is not unprecedented. The two BP rig bosses on the Deepwater Horizon were charged with environmental crimes and 22 counts each of manslaughter after the deadly 2010 disaster, but in the end only one of them was convicted on a single pollution count.

Walter Oil & Gas was sentenced early this year to pay a fine of $400,000, or about twice the amount of a day’s rig-leasing fees.

Court papers say the company would have saved $200,000 by not taking an additional day to remove the material from the pipe properly, and federal law allows a penalty equal to twice the amount gained by committing the crime.

But Servos said if the company had been charged with all of the violations alleged by Howington, the government could have collected $28 million.

For example, Servos said, Walter Oil & Gas could easily have been charged with a felony intentional discharge, in addition to the failure to notify authorities.

The formal charges, as spelled out in the company's guilty plea, say the company violated the Clean Water Act by failing to report an accidental spill that happened when they were trying to clear the pipe the correct way, on March 31, 2014. It notes that the crew left the valve open the next morning but says nothing about it being intentional.

In a letter to the court, Maestri stood by the decision to charge Walter Oil & Gas for failing to report the discharge, noting that the fine for that felony is larger than the one for an intentional discharge.

The U.S attorney in New Orleans, Kenneth Polite, stood by Maestri’s handling of the case. He said he couldn’t comment in detail about Howington’s allegations because his claim against Maestri is still pending with the Justice Department in Washington.

“I can state confidently, however, that Walter Oil pled guilty to an environmental criminal charge appropriate to the facts and evidence,” Polite said. “Further, our office timely responded to the questions and concerns of Mr. Howington's counsel. Ultimately, I expect Mr. Howington's claim to be denied.”

In addition to charging the company under the Clean Water Act, the feds could have used a law called the Act to Prevent Pollution from Ships, or APPS, to charge Walter with 24 days of allegedly allowing hydraulic oil to leak into the sea from the rig floor, Servos said.

APPS provides whistleblowers with the ability to collect a share of fines collected, and Servos said that would have made Howington eligible to collect up to $6 million.

But Maestri wrote in emails to Servos that APPS did not apply in this case, arguing that “the incident obviously did not involve a vessel or ship that is capable of being used as a means of transportation.”

And yet, Maestri referred to the floating rig, called the Uncle John, as a motor vessel in court documents.

The rig sails under its own power and, in this particular case, transported Howington and the rest of the crew hundreds of miles across the Gulf, from Pensacola, Florida, to the well site 60 miles off Port Fourchon.

Still, Howington may not have had strong enough evidence for the feds to charge Walter at all for the hydraulic oil. A government official with knowledge of the federal investigation told WWL-TV that agents were not able to find enough clear evidence to prove the oil on the rig floor actually spilled into the Gulf.

Before the sentencing, Howington sent a letter to U.S. District Judge Nannette Jolivette Brown, saying the proposed guilty plea did not approach the breadth of the crimes he had documented. But the letter was never placed in the court record because Maestri argued that Howington was not a “victim” and had no standing to file anything in the record.

Environmental watchdogs argue that Howington and other whistleblowers are, in fact, victims — victims of an industry that professes to support those who stand up for safety and the environment but often blackballs those who don’t “go along to get along.”

Raleigh Hoke of the New Orleans-based Gulf Restoration Network said offshore whistleblowers deserve more protection from the government, including compensation.

“What Evan did was incredibly brave. I mean he put his livelihood and his future on the line to hold this company accountable,” Hoke said. “If Evan's bravery didn't lead to actually this company being fully held accountable, can we really expect other whistleblowers to come forward when they see something?”

Offshore workers do not have the same legal protections as other industrial workers, and several attempts by former U.S. Rep. George Miller, D-Calif., to grant whistleblower protection to offshore workers were blocked by Republicans in Congress.

Still, Howington said he doesn't regret coming forward.

“If you take me back there, I'd do it again; I'll report it again,” he said. “It's wrong. It's illegal. It's against the law, and it puts everyone at risk. And it needs to be dealt with.”