Man in charge of Archdiocese’s $40 million bankruptcy makes stunning admission

Meanwhile, the nearly $40 million in expenses resulting from the bankruptcy so far are already more than five times higher than initially projected.

A US government official is questioning the soaring legal fees paid by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New Orleans after the volunteer managing the organization’s four-and-a-half-year-old bankruptcy admitted under oath to a stunning lack of qualifications for his role.

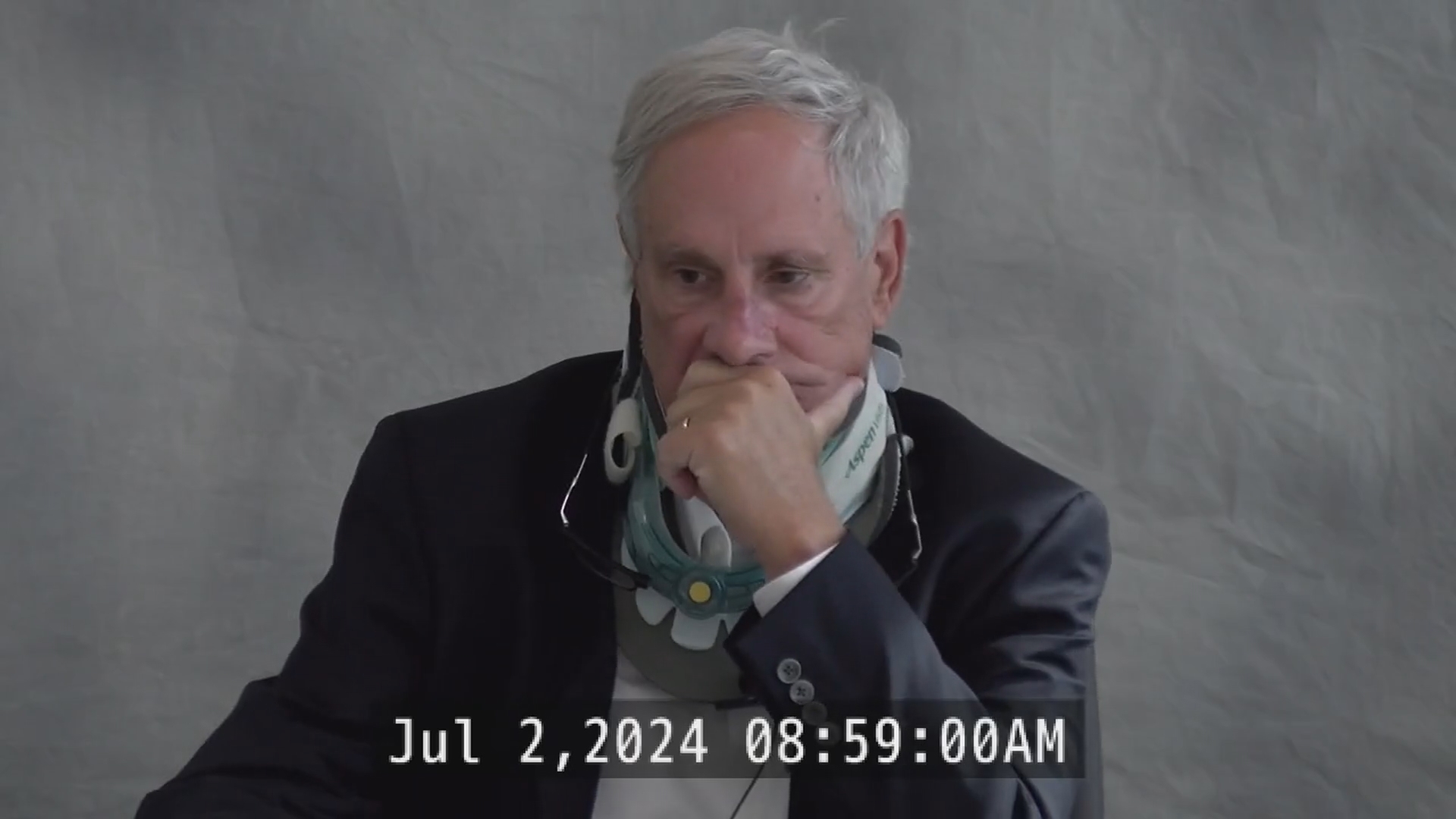

Local businessman Lee Eagan testified in early July to having never previously policed the costs of a bankruptcy as well as failing to familiarize himself with the rules for that kind of proceeding. In a separate series of earlier depositions, he also swore to grappling with substantial cognitive decline after a severe car crash nearly two years beforehand.

Meanwhile, the nearly $40 million in expenses resulting from the bankruptcy so far are already more than five times higher than initially projected.

None of the money spent so far has gone to roughly 500 people who have filed claims in the bankruptcy alleging that they were victimized, mostly as children, by the ongoing clergy molestation and cover-up crisis within the archdiocese. Survivors and their supporters are worried that victims’ prospects of one day being made relatively whole by the church may dim if expenses aren’t reigned in.

Eagan does not have ultimate authority over whether fees should be paid by the church. The US trustee—a neutral bankruptcy court official from the federal justice department—and the bankruptcy judge are supposed to review the legal and professional bills that Eagan submits to the court. The court has approved all of the church's legal fees to the penny, according to court records.

Recently, the US trustee recommended holding back 20% of all legal and professional fees because the church has yet to submit a reorganization plan. And there is no clarity when the case — filed largely to help the archdiocese manage the fallout of a decades-old clergy abuse scandal — may conclude.

Eagan’s sworn testimony in a July 2 deposition – as well as in earlier, similar sessions pertaining to litigation related to the vehicle wreck – prompted some attorneys for clergy abuse claimants to ask the US trustee to request the removal of Eagan from his role. They suggested someone from outside the second-oldest American archdiocese be put in charge of approving legal fees and other costs stemming from the bankruptcy, according to a letter they sent to the US trustee.

The US trustee’s office declined to take a position with respect to Eagan’s removal. Nonetheless, the request has thrust Eagan under scrutiny after he approved more than $38 million in legal and professional fees alone, through June, for a bankruptcy case that New Orleans archbishop Gregory Aymond once estimated in a letter to the Vatican would cost $7 million total.

Court records show about $13 million of those fees had gone to the archdiocese’s own bankruptcy lawyers – among them the husband of the church organization’s in-house lawyer.

Even Eagan, 72, himself answered “yes” when asked in July if he “would like to see the archdiocese pay less in fees.” And, asked whether he knew if Aymond believed “costs relative to [the] bankruptcy are excessive,” Eagan replied, “Yes.”

Aymond, in fact, “says we need to settle this bankruptcy as quickly as possible,” Eagan said.

However, Eagan also testified to essentially negotiating in bad faith during mediation sessions meant to help the church reach a legal settlement with abuse survivors and other creditors ensnared in the bankruptcy. He described reflexively contradicting survivors’ attorneys even when he couldn’t think of a reason – a posture that is only adding to the costs.

“They [say] the wall’s blue – I’ve got to say, you know, ‘I’m not sure it’s blue. I think it's pink,’” Eagan testified during the earlier car crash depositions, despite rules prohibiting mediation participants from discussing the talks with outsiders.

One attorney who filed a disability discrimination lawsuit against the bankrupt archdiocese—which spent hundreds of thousands of dollars unsuccessfully appealing to make the case part of the bankruptcy—said Eagan’s admissions made sense to a point.

“It’s not surprising because it’s clear that whoever’s running the show doesn’t know what they’re doing,” said the lawyer, Chris Edmunds.

Asked by the Guardian and WWL Louisiana whether it would consider substituting Eagan, the archdiocese responded with a statement alleging a “direct character assassination.” The statement didn’t address the content of Eagan’s testimony but blamed the attorneys upset with his performance in the bankruptcy “for the unacceptable time and costs” spent on the proceeding.

“Mr Eagan has worked tirelessly and selflessly to manage this process as a volunteer and without compensation,” said the archdiocese’s statement, which also called him “a man of faith and integrity who works closely with competent and experienced professionals to share their expertise in the reorganization process.”

The statement added: “To imply that his role has been (the) cause of the delays is incorrect and detrimental to the process that we hope will bring closure and compensation for the abuse survivors.”

A separate statement attributed to Aymond said he stood by Eagan’s “professionalism, skill and business acumen together with his integrity and strong faith and loved for the church.”

“I have never considered removing Lee Eagan from his role in the bankruptcy,” Aymond said. “I have complete faith in his abilities and his desire to help move the local church forward and remain grateful for his selfless commitment to the church and this process.”

Also, during Eagan’s more recent deposition, one of the church’s bankruptcy attorneys – R Patrick Vance – accused reporters for the Guardian and WWL of being “advocates” and referred to their unflattering but award-winning journalism on his clients’ management of the clergy abuse scandal as “an argumentative position paper”.

Details of Eagan’s testimony are coming to light as the archdiocese navigates an investigation by Louisiana state police into whether the organization – which ministers to about a half-million Catholics – enabled the “widespread sexual abuse of minors dating back decades.” A search warrant that state troopers served on the archdiocese in April also mentioned evidence that the institution had covered up child molestation rather than report it to law enforcement.

'Makes no sense'

Eagan’s sworn testimony is not under court seal — unlike most of the rest of the case’s filings — and is circulating among some members of New Orleans’ legal community.

Among its most illuminating aspects is his lack of prior experience policing bankruptcy-related expenses.

Eagan, the chief executive officer of an industrial supply company who dedicates some of his free time to community service at a group home for people with developmental disabilities, is not an employee of the archdiocese but has volunteered to work on its financial advisory committee for about a decade. He testified that Aymond assigned him to “review all bills relative to the bankruptcy” after it filed for reorganization in May 2020.

That is the case even though Eagan confirmed that all of those bills are addressed to the archdiocese’s general counsel.

While being deposed by attorney Richard Trahant, who represents a large contingent of clergy abuse claimants, Eagan acknowledged he was neither a certified public accountant, a licensed financial adviser, nor an expert in bankruptcy. He also said it was “correct” for Trahant to say Eagan had no “education, training, or experience to be a bankruptcy expert.”

Eagan furthermore admitted to Trahant that he had never before even seen the federal bankruptcy rules and guidelines governing compensation of professionals working on a Chapter 11 reorganization like the archdiocese’s.

The rules are meant to minimize – if not eliminate – payments to multiple attorneys or other professionals for performing redundant tasks, among other things. And if followed, they are also supposed to prevent different professionals working on the reorganization to bill disparate amounts for relatively similar tasks.

Yet Eagan said he had “never” seen those rules until Trahant handed a printout of them to him at the deposition.

“And so you’re seeing that for the first time today? … As the individual responsible for the billing issues for [the archdiocese], not only have you not reviewed these guidelines, you did not know until today that they existed, correct?” Trahant asked. Eagan replied: “Yes. That is correct.”

Trahant said that was obvious to him from scrutinizing some of the expenses Eagan had authorized. Trahant singled out that one of the archdiocese’s bankruptcy attorneys—from the Jones Walker law firm—had billed $150 to review a one-sentence court filing that took Eagan about five seconds to read during the deposition. Another lawyer at the same firm billed $40 to provide a second review of the same document.

Additionally, Trahant established that Wayne Zeringue – yet another Jones Walker attorney – had frequently billed the archdiocese’s bankruptcy for conversations he had with the archdiocese’s general counsel, Susie Zeringue, who is his wife. He also established that Aymond had repeatedly told the public that he supported legislation allowing survivors of child molestation in Louisiana to sue for civil damages no matter how long ago they were abused – before Eagan authorized the archdiocese’s bankruptcy attorneys to charge the church over and over to support unsuccessful efforts to get that law struck down as unconstitutional.

Jones Walker attorney Mark Mintz, who has represented the church most prominently in bankruptcy proceedings, testified separately that his firm’s work for the church began with meetings among Eagan, Wayne Zeringue and Susie Zeringue. Trahant’s colleague, Soren Gisleson, asked Mintz whether Wayne Zeringue would collect an “origination fee” for bringing the case to Jones Walker. Mintz declined to answer, saying the information was “proprietary”.

Edmunds, the lawyer who filed the disability discrimination case against the archdiocese, said origination fees are often about 10% of the total legal billings—which would equate to $1.3 million of the $13 million paid so far to Jones Walker.

Edmunds said he was shocked as the church’s lawyers spent $320,000 trying, unsuccessfully, to transfer their dispute from state court to the bankruptcy system. As Edmunds explained, “It’s a pretty fundamental tenet of bankruptcy law” that the church’s Chapter 11 protections would only apply to cases from before the organization declared itself bankrupt. His case alleged post-bankruptcy wrongdoing, but the archdiocese still went for it – and failed.

“They spent a whole ton of money based on the premise that it would cost money to defend the suit,” Edmunds said. “It makes no sense.”

As just one example from his case, Edmunds said he moved to recover $11,000 in legal fees he incurred litigating the venue where the case should be heard – and the archdiocese spent $15,000 fighting that.

“Someone needs to explain why you spent $15,000 in fees to avoid $11,000,” he said.

Jones Walker did not reply to questions about Eagan’s testimony but said:

“Our bankruptcy attorneys have decades of experience and hold themselves to the highest degree of professionalism. In addition, we have worked daily with Lee Eagan and know that the attacks on him are unprofessional and scurrilous.”

'Biden issues'

Trahant at one point asked Eagan why the archdiocese would oppose someone with “no connection to any of this … reviewing, without favor or anything else, all of the bills in this case”. Eagan replied: “There’s a cost issue there, and I weighed the risk-rewards … analysis in my mind, talking to others outside of this bankruptcy. And I’ll tell you that I didn’t like the cost benefit.”

Trahant made clear how little he thought of Eagan using his mind for calculations. That is because, after suffering a neck injury in a three-car crash in October 2022, Eagan endured substantial cognitive impairment, according to three depositions he gave between February and March in a lawsuit centering on the accident.

Eagan recounted one episode where he suddenly forgot the name of someone at the archdiocese that he saw weekly. He needed to look at that person’s name tag to remember the individual, said Eagan, who wore a neck brace during his deposition with Trahant.

He said he began veering to the left whenever he walked. He said he would need to script his meetings when, before the wreck, he could improvise his way through them without requiring much preparation. He said he took six weeks off after undergoing surgery for his neck injuries – but could not say who, if anyone, assumed his duties while the bankruptcy expenses kept rapidly accumulating.

Eagan added that he would spend his afternoons after the wreck “just taking balls and strikes,” a baseball metaphor for merely standing in the batter’s box without swinging.

At one point, he said his cognitive decline had not been as bad as President Joe Biden’s – but almost.

“I’m not having Biden issues, where I forget where I am, right?” Eagan said, nearly five months before the president quit his re-election campaign over voters’ concerns about his mental acuity. “But … I can tell you that, since the date of the accident, that memory recall [problems], especially of names, is more pronounced.”

In his deposition a day later, Mintz said he had known of Eagan’s crash. But Mintz said Eagan’s testimony to Trahant marked the first time he had heard of the church bankruptcy manager’s cognitive impairment.

Eagan later tried to persuade Trahant that he was getting better with time, and his cognitive problems only surfaced when he took certain medications meant to help him cope with the effects of the crash.

Trahant countered that Eagan had never before attributed his self-described cognitive decline to his medication while highlighting a number of discrepancies between his testimony that day and what he had said in the previous depositions.

In a bizarre moment during their faceoff, Trahant asked Eagan if he lived by the honor code of Robert E Lee, the Confederate general who owned enslaved people and commanded the white supremacist, losing side of the US Civil War.

“Absolutely. Do you? I mean – he’s a good guy,” Eagan said, hewing closely to testimony he had offered months earlier in reference to Lee, whose monument was removed by New Orleans – which is majority Black and has the highest percentage of Black Catholics of any major American city – in 2017.

Eagan noted that the military figure had also been president of Washington & Lee University, whose student-led honor code forbids lying, cheating or stealing.

“A gentleman shall behave as a gentleman,” Eagan said.

Eagan ultimately confirmed to Trahant that he had agreed to an out-of-court settlement of a lawsuit he had filed after the car wreck. In exchange, Eagan was awaiting a check for $1.15 million, though he intended to demand more money from the company holding an insurance policy shielding him from underinsured motorists, according to his testimony.

Trahant asked Eagan: “Wouldn’t you agree that victims of child sexual abuse deserve at least as much money as you’ve gotten for a neck injury?”

Vance, Eagan’s attorney, did not let him answer the question.

► Get breaking news from your neighborhood delivered directly to you by downloading the new FREE WWL-TV News app now in the IOS App Store or Google Play.

* This article was amended on August 7, 2024, to include a statement from the Jones Walker law firm.