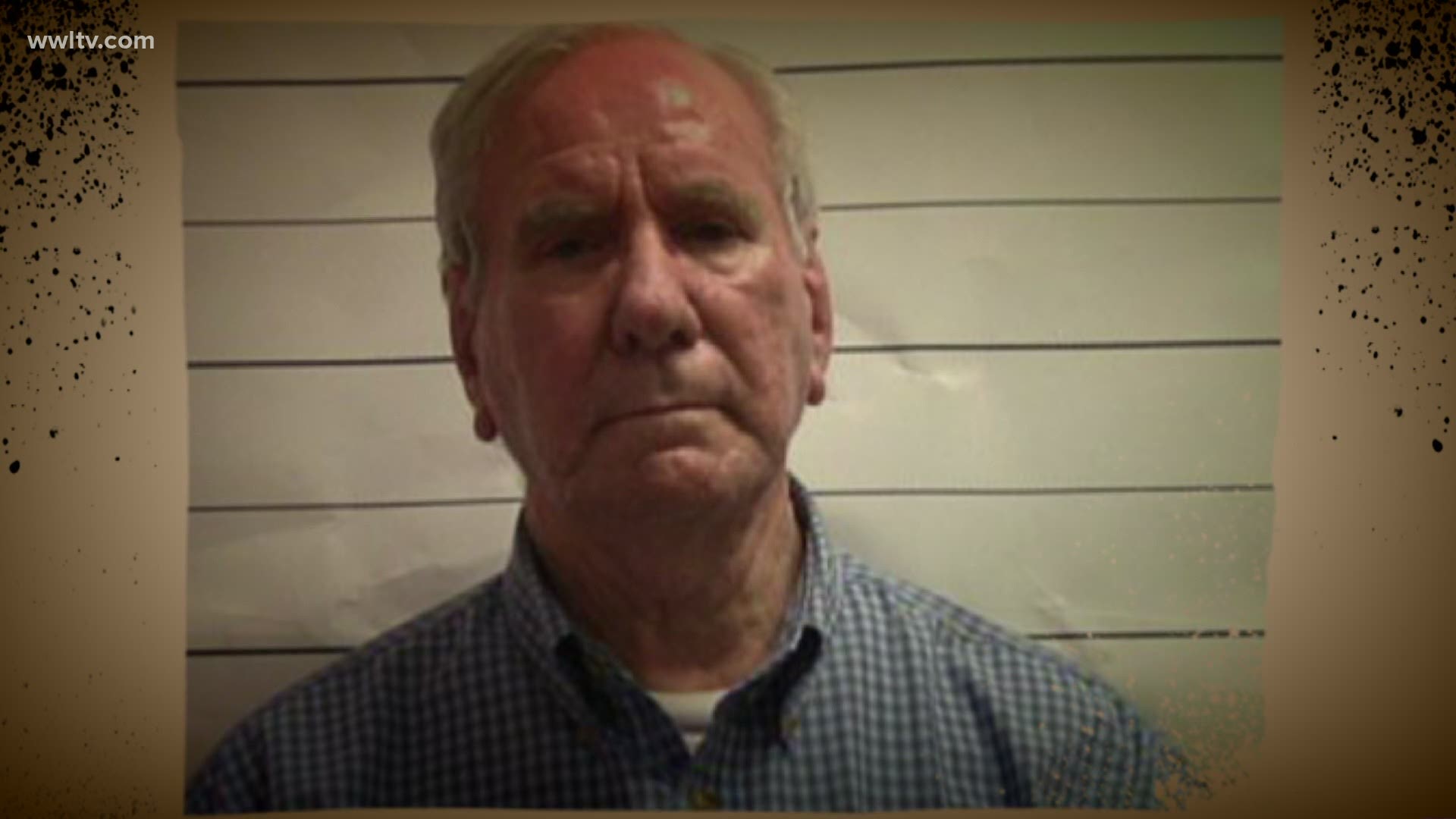

NEW ORLEANS — Anyone else in George Brignac’s shoes -- saddled with the disgrace that accompanies his name -- might have gotten the hell out of Dodge and tried to reinvent himself, to outrun the shame.

Over the 12 years he served as a deacon at Our Lady of the Rosary Church, beginning in 1976, Brignac had been accused of molesting at least five boys and was arrested by authorities at least three times.

Brignac, who was also a schoolteacher, was never convicted. But he was forced to sign an agreement, under duress, to stay away from children. And, though some fellow priests objected, the Archdiocese of New Orleans suspended him from ministry in 1988.

Just 53 at the time, Brignac fretted about his next move. It isn’t entirely clear what he did over the next decade. But he had no intention of giving up his involvement with the Catholic Church, which would ultimately open its doors again to him in a way that allowed him access to children, according to thousands of pages of documents in Orleans Parish prosecutors’ files that were released after Brignac’s death earlier this year.

The local Knights of Columbus, a Catholic community service organization, accepted Brignac in 1998, just 10 years after his suspension.

In a statement this week, a Knights spokesperson said the organization -- which is separate from the archdiocese -- wasn’t “aware of Mr. Brignac’s history” at the time. The spokesperson said the Knights don’t run background checks on new applicants because the organization isn’t focused on youth services.

Over the next 20 years, Brignac would hold a range of several different volunteer titles there, including that of “chaplain” and “faithful friar,” which are typically reserved for priests, records say.

Brignac’s association with the Knights survived a 2002 Boston Globe investigation that showed the worldwide church had covered up thousands of cases involving clergymen who had molested children.

The scandal did cause Brignac some grief. It prompted then-New Orleans Archbishop Alfred Hughes to convert Brignac’s indefinite suspension from the clergy into a permanent one, at the suggestion of a board reviewing abuse cases.

In a 2002 letter, Hughes recommended that Brignac ask the Vatican to remove him from the clergy through a process called “laicization.”

Brignac wasn’t interested. He complained in a letter that Hughes had acted “without any consultation with me.”

Brignac said he had sought counsel from people he trusted and respected.

“I have been advised and I agree that I should do nothing about my status that would imply even in the slightest way that there is any credence to the allegation against me, which is false,” Brignac said. “My position is so obviously correct that I am confident you would concur in it.”

There is no indication Hughes pursued laicization any further. He didn’t immediately respond to a message seeking comment.

‘Innocent until proven guilty’

Brignac was continuing to serve as a Knights of Columbus officer when, in 2009, he encountered the Rev. Robert Massett, the pastor of Metairie’s St. Mary Magdalen Church.

Soon, the pastor was recommending Brignac to read Scripture at Masses at St. Mary Magdalen, where the Knights have a chapter, the pastor told an investigator many years later.

Massett, who retired in 2016, said he knew at the time that Brignac had been arrested multiple times on molestation allegations, and that that record had cost Brignac his career in teaching as well as his Roman collar.

Inexplicably, about the time of Massett’s invitation in late August 2009, two months into current Archbishop Gregory Aymond’s stint in New Orleans, Brignac was allowed to complete an archdiocesan course aimed at ensuring the church doesn’t give child molesters like him access to kids. The course, developed in the wake of the 2002 scandal, trains church personnel to prevent and report child abuse.

Despite knowing about Brignac’s abhorrent past, Massett signed the ex-deacon’s paperwork. Since then, additional safeguards have been added where the program’s coordinator is automatically alerted about any concerns on paperwork, the archdiocese said.

But those didn’t exist at the time, and Brignac sailed on through the course.

In a recent interview, Massett said he believed Brignac was worthy of a second chance and should be considered “innocent until proven guilty.” Massett claimed he had been told that one of Brignac’s accusers had recanted. But that accuser has never recanted.

In any event, Massett said, the church was not going to let the disgraced deacon work with children.

“As long as he is not involved with children, what’s wrong with a man being involved with the church?” Massett said.

Massett ultimately learned that restriction hardly deterred Brignac.

Massett later told District Attorney Leon Cannizzaro’s office that several parents had approached him to warn him that Brignac was cozying up to a child in a wheelchair. In a recent interview, Massett downplayed the seriousness of Brignac’s advances, saying he only saw Brignac talking to the boy once, and that a parent put a stop to it.

In a recent interview, the boy’s mother, who asked to not be identified, told reporters a much more chilling story. She said Brignac met her son while the boy took classes, sponsored by the Knights, meant to prepare children to receive the sacraments.

Throughout her son’s four years as an altar boy, starting in about 2011, Brignac would talk to him after Mass, she said. The mom recalled Brignac often told her that her son was welcome to come over to his home anytime.

He would also send the boy birthday and Christmas cards, and little gifts, like magnets and other knickknacks, she said.

But she never allowed Brignac to be alone with her son.

“We didn’t even really know him,” she said. “We just knew him from the 10 minutes we would spend with him after church.”

She described herself as equally relieved and disturbed when the full truth about Brignac came out. She said she strongly suspects Brignac was grooming her son to become his next victim, perhaps sensing the boy’s physical disability might make him an easier target.

“I feel like if we hadn’t had complete supervision of (the boy), that wouldn’t have gone well,” the mother said. “That would’ve been bad.”

Coming forward

That wasn’t Brignac’s only recent close encounter with children that was facilitated by the church.

In 2017, in his role with the Knights of Columbus, Brignac spoke to a group of kids at St. Mary Magdalen about a century-old miracle in Portugal. For a feast and procession commemorating the apparition of the Virgin Mary, Brignac also suggested having three students wear Portuguese “period dress,” emails show.

Both the school and the Knights were effusive after the event.

“George Brignac has spent a great deal of effort explaining to our members the various facts of the Fatima appearances,” the leader of the Knights chapter wrote the school principal. “To do so to the children today was very special for him. And our entire (chapter) as well!”

The principal wrote back: “You are so welcome! Thank you for thinking to include the school. Today was very touching!”

Less than a year after Brignac’s Fatima triumph, two unrelated major developments exposed his problematic ongoing association with the Catholic Church.

First, the Diocese of Erie, Pennsylvania, in April 2018 published a list of 34 priests and 17 laypeople faced with credible accusations of child sexual abuse, ahead of a state grand jury report detailing hundreds of other Pennsylvania cases that had previously been concealed.

Meanwhile, a Slidell man filed a lawsuit alleging that he had been anally raped by Brignac over a five-year period beginning in 1978, when the plaintiff was an altar boy at Our Lady of the Rosary.

The archdiocese and the plaintiff, represented by attorney Roger Stetter, soon agreed to settle the case out of court for $550,000 -- a large sum for a decades-old abuse claim.

Initially, Stetter’s client had asked that the size of the payment remain confidential. But after the agreement was struck, the plaintiff dropped that request.

He and Stetter spoke to the local news media about the settlement. And it changed everything.

Brignac by then was about to turn 85. At last, his story was coming to a close.

► Get breaking news from your neighborhood delivered directly to you by downloading the new FREE WWL-TV News app now in the IOS App Store or Google Play.