JEFFERSON PARISH, La. — It’s a rare thing to hear from any public official:

“It was my mistake.”

But that’s how the former landfill engineer for Jefferson Parish describes his decision in 2016 to accept hydrated lime at the parish landfill in Waggaman. And after running the parish landfill for 23 years, Rick Buller says it was that “honest mistake” that most directly caused gas emissions to spike.

The state Department of Environmental Quality and others say those gases from the landfill most likely caused a sickening odor to descend on neighborhoods along the Mississippi River.

In an interview, Buller said parish leaders have focused on the wrong potential sources of the odor problem, 15 months after he was forced to resign in July 2018 amid an avalanche of angry resident complaints.

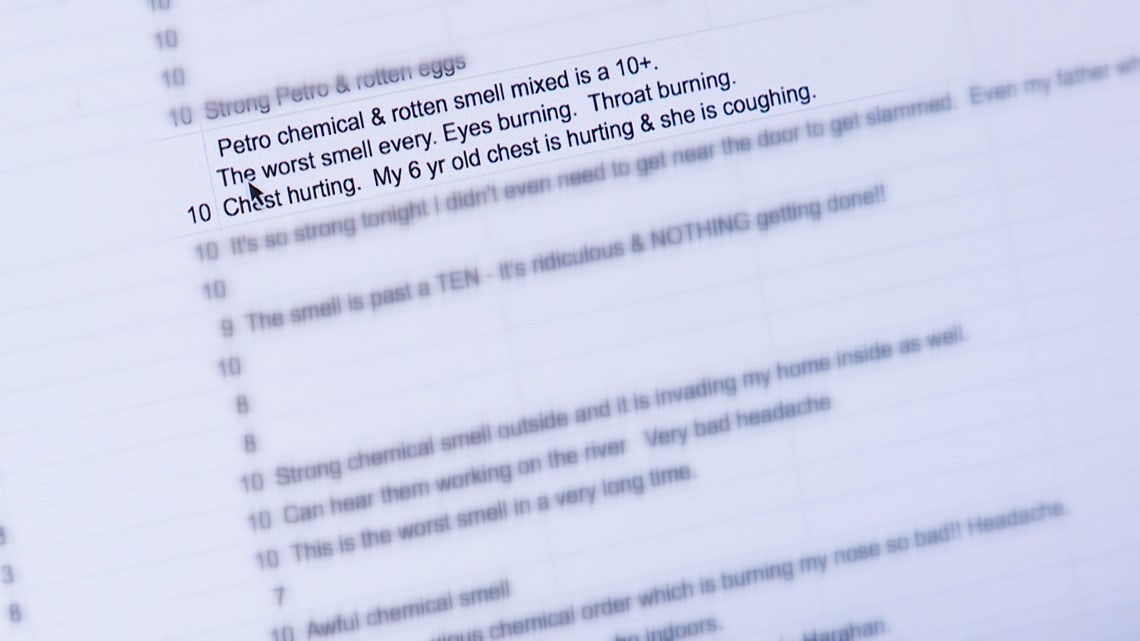

“I've had headaches,” Waggaman resident Karen Hebert said. “I've had tightness in my chest. Eyes burning. Skin burning when you're cutting the grass or something and the smells out here. You get it on whatever exposes, that's where you get the tingling and the burning.”

Almost 3,000 other residents have filed “smell reports” to a Facebook group. For the last two years, they have been collected and entered into a database by Harahan resident Gerald Herbert.

INTERACTIVE MAP: Thousands of complaints of Jefferson Parish mysterious smell

“People are livid. They get depressed. They get angry,” Herbert said. “And it’s no way to live your life when you’re sitting outside, trying to enjoy your evening, and all of a sudden you start to get stunk out, and then you go inside, and it starts getting in your house. That’s no way to live.”

“I’m sorry,” Buller said when asked if he had anything to say to those residents. “I worked for 23 years and always had the interest of Jefferson Parish as my top priority. People may disagree with decisions I made, but I always made them with honesty and integrity. And I never accepted any illegal or unethical benefits from anyone.”

But Hebert, Herbert and others say Buller isn’t to blame. They think he has been unfairly scapegoated by parish leaders. They say he was the one who showed the most concern when they first started complaining about the smells in 2018.

“He was driving around, checking it out, he would come by my house and report to me what he was looking for,” Herbert said. “And I appreciated that. He seemed very earnest in that regard, that he cared.”

While Buller strongly believes the parish has misdiagnosed the real source of the odors, he isn’t convinced that the gas escaping from the parish landfill is strong enough to cause residents’ health problems on the other side of the river.

For one thing, Buller said none of the landfill workers have exhibited the symptoms being reported by residents.

What’s more, little is known about the relative impact of three other landfills and a slew of chemical plants in the same area, and barge-loading operations along the section of the river between Waggaman and Harahan.

But environmental experts agree the worst smells and health impacts people in the area have experienced can be attributed to emissions of hydrogen sulfide -- known by its chemical formula, H2S.

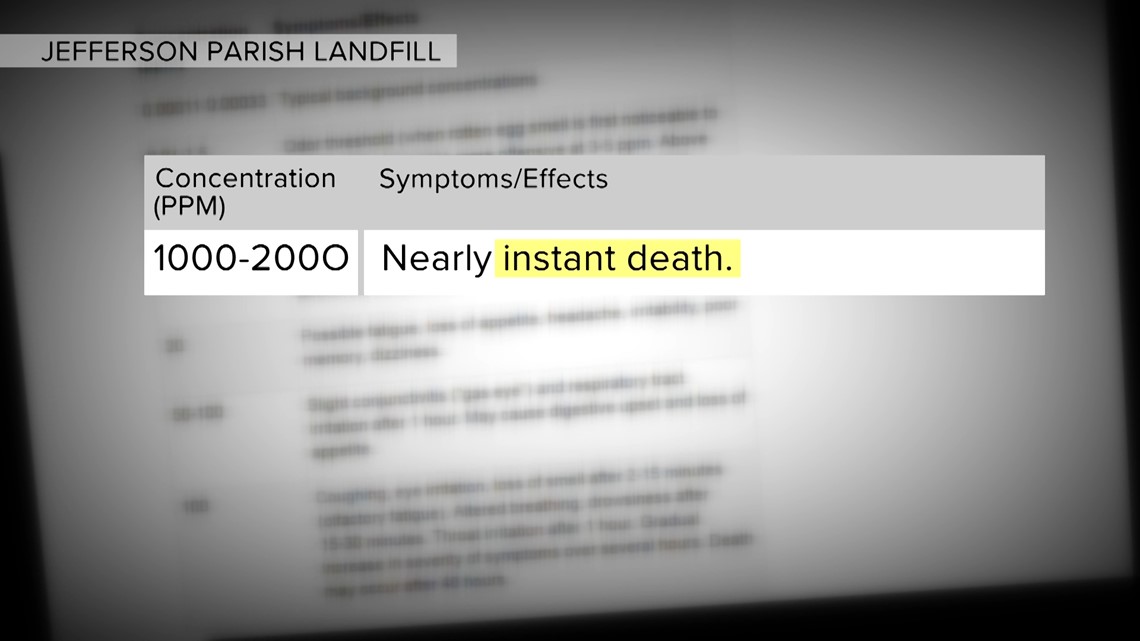

At concentrations of just a few parts per million, H2S smells like rotten eggs and can cause minor health issues. And air monitoring shows highly elevated H2S levels at the parish landfill.

The neighboring, privately owned River Birch landfill measures H2S inside its gas collection system at 80 parts per million. By contrast, some of the gas wells inside the Jefferson Parish landfill have measured at or above 2,000 parts per million – 25 times as high.

A chart prepared by the parish’s environmental consultant said anything over 1,000 parts per million of H2S would cause “near instant death” to a person not wearing any protection. But even on the parish landfill site, the highest concentration of H2S measured outside the wells, above cracks in the ground cover, has been 45-60 parts per million, according to the parish’s environmental consultant.

Buller explained that he agreed to accept hydrated lime -- a white, powdery carbon waste product --because it was a significant source of new royalties for the parish. He said it was tested for hazardous material and found non-hazardous before he agreed to accept it.

He said he didn’t realize until it was too late that the lime contained sulfates, which aren’t dangerous by themselves but would release huge amounts of hydrogen sulfide once they mixed with liquids and other wastes inside the landfill.

“This was obviously non-hazardous, so I accepted it,” he said. “In hindsight, we should also include something that looks at the concentration of sulfates within the waste stream. It was sometime in April or May of 2018 that I realized that this was the culprit.”

By then, the landfill had already buried 18,600 tons of hydrated lime from mid-2016 through mid-2018, mostly from the Rain Carbon plant in Chalmette. The lime accounted for about a quarter of all industrial waste the landfill accepted over that two-year period, according to state records.

But parish leaders never heard Buller’s theory that the lime was the primary source of H2S.

Buller says that’s because by the time he realized it, Parish President Mike Yenni’s administration didn’t trust him anymore and wouldn’t listen to him.

He said public officials were misattributing the gas emissions to liquid industrial waste that started coming into the landfill at the same time as the lime, and to the landfill’s malfunctioning gas collection system.

In a statement Friday evening, the Yenni administration said: "While there was no evidence that liquid industrial waste contributing to H2S emissions, this administration chose not to accept liquid industrial waste. When surface methane exceeded normal levels, this administration learned the extent of improvements needed to correct the landfill gas collection system, and this administration has invested millions of dollars to repair and upgrade that system."

The gas collection system is undoubtedly critical for stopping high H2S and methane emissions. Buller says fixing it is the only way to mitigate the problems he believes were caused by the hydrated lime buried in the newest section of the landfill, Phase 4A.

But public records show the gas collection system started malfunctioning long before any spike in complaints about odors wafting across the river.

Gas collection wells in completed sections of landfill are supposed to suck in gases like methane and H2S and pump them out to a gas plant. But many of Jefferson Parish’s 225 gas wells were flooded with liquid called leachate that builds up at the bottom of piles of garbage. The landfill’s leachate pumps were supposed to remove that liquid before it could block the wells, but they were not properly maintained, Buller said.

Emails from 2013 show Buller trying to get contractors to fix the leachate pumps. He said a rocky transition from one landfill operator to another – from Waste Management to IESI in 2012 -- exacerbated the landfill’s serious maintenance problems.

“We, including myself, Jefferson Parish, needed to do a better job with the contracting and the transition between Waste Management and IESI,” he said. “I think that’s where a lot of these problems with landfill maintenance broke down.”

But Buller said those maintenance issues are irrelevant to determining why the odors got bad in the first place. Most landfills collect waste for five years before installing any gas collection system. Phase 4A, the area of the Jefferson Parish landfill with the worst H2S emissions, wasn’t even scheduled to have any gas wells and pumps installed until 2018, and by then the odor problems were already bad.

At a news conference in July 2018, Yenni acknowledged the landfill was at least partly responsible for “unacceptable” offsite odors, but he also pointed fingers at his predecessors for “kicking this can down the road.”

Yenni’s immediate predecessor, John Young, fired back, blaming Yenni for accepting liquid industrial waste that the Young administration never allowed and neighboring landfills like River Birch refused to take.

“The one defining issue is Yenni's administration accepting liquid industrial waste and those complaints in Harahan and River Ridge spiking,” Young said.

"When odors emanating from the landfill became persistent and pervasive, Parish President Yenni instructed his top administrators to determine the root cause of both the leachate system and gas collection system’s continual failure to operate properly," Yenni spokeswoman Samantha DeCastro said in an email. "The Yenni administration began to institute remedial measures to fix the myriad of landfill problems and have since invested millions of dollars to upgrade the landfill without kicking the can down the road."

Buller said he was essentially fired in July 2018 when the Yenni administration forced him to retire six months earlier than planned. He said it was because he had accepted outside sources of liquid industrial waste.

The DEQ issued the parish a permit in March 2016 that allowed it to accept outside liquid industrial waste, such as wastewater from chemical plants or sewer sludge. But that permit allowed more than the parish had actually sought.

Buller said he learned later that the Yenni administration only wanted that permit so it could solidify liquids already found on the landfill site, such as runoff from cleaning trucks or equipment.

“I thought I had the authority” to take off-site liquid industrial waste, Buller said. “Obviously, the administration thinks otherwise.”

The Jefferson Parish Council passed a moratorium on taking any industrial waste, solid or liquid, starting July 25, 2018.

Every week since then, the parish has posted a weekly report stating, “No industrial wastes were received at the landfill as the moratorium is still in place for these materials.”

That includes the report covering the week of Jan. 26 to Feb. 1, 2019. But a document filed with the DEQ shows that on Jan. 28, the landfill did accept 1.1 tons of industrial sludge that had been dug up from the nearby Cornerstone Chemical Plant.

“For us to trust the government in saying they stopped it, and to know they’re still doing it; if it’s true, it’s terrible,” Hebert said.

In addition, the Yenni administration acknowledged Friday another 1,100 tons of industrial waste that was erroneously accepted at the landfill after the moratorium. DeCastro said records were corrected and sent to the state DEQ.

But Buller emphasized that liquid industrial waste is not the cause of the gas emissions and refusing to accept it will only cost the parish revenue.

“In fact, cutting off any industrial waste isn’t going to address the problem,” he said. “The problem is the lime that’s already buried within Phase 4A.”

Smell Complaints Interactive Map:

Previous Coverage:

► Get breaking news from your neighborhood delivered directly to you by downloading the new FREE WWL-TV News app now in the IOS App Store or Google Play.

WWL-TV Investigator David Hammer can be reached at dhammer@wwltv.com;