NEW ORLEANS — The Louisiana Supreme Court heard arguments Monday that could decide the future of hundreds of child sexual abuse claims and lawsuits filed under a 2021 state law, which removed old deadlines for filing such claims during a three-year lookback window.

The state’s highest court heard from lawyers representing alleged abuse victims and also from an attorney representing a Catholic Church organization being sued over the actions of a priest it employed in 1965.

The court is being asked to decide whose rights are more important – the property rights of alleged abusers and their employers to be protected from being sued once a deadline has passed, or the rights of their accusers to sue now that the old deadlines have been removed.

The decision could have a major impact on about 500 sexual abuse claims filed against the Archdiocese of New Orleans in its federal bankruptcy case. It also affects any civil claims against alleged abusers unrelated to the church.

But many of the entities arguing the state’s lookback window to revive old abuse claims is unconstitutional are affiliated with the Catholic Church, including Jesuit High School and Holy Cross College in New Orleans.

Attorney Ian Atkinson argued in front of the Supreme Court justices that his client, Congregation of the Holy Cross Southern Province and Holy Cross College, had a vested right against being sued as soon as the legal deadline to sue in 1965 had passed, which was one year from the alleged abuse. Once such a right had vested, the Legislature can never take it away, Atkinson argued.

He said that position is “consistent with a long line of Supreme Court cases stating that vested rights are protected in Louisiana and that revival (of the right to sue) is not allowed because it would deprive the defendant of the vested right to plead prescription.”

Prescription is the Louisiana term for a statute of limitations. Atkinson argued any kind of claim for civil damages, whether from sexual abuse or a hurricane, should be barred once that specific statute of limitations is reached. But at one point, even Atkinson acknowledged child abuse claims could be viewed differently than other tort claims.

“I think everybody here would agree that the abuse of a child is probably the most unforgivable thing that any of us could think of,” Atkinson said.

That’s when Justice William Crain jumped in and said: “And that's just what the legislature has done, is said this is going to be unforgivable.”

Camille Gauthier argued on behalf of the alleged victim in the Holy Cross case, identified only by the initials T.S. She said a lower court had erred when it ruled in favor of Holy Cross and declared the lookback window unconstitutional.

She said the property rights of alleged abusers and their employers can be limited by the Legislature, especially when the lawmakers clearly spell out their intent to remove the statute of limitations as they did in this case.

They overwhelmingly approved a lookback window in 2021 and clarified their intent in 2022 based in part on social-science research finding child sexual abuse victims are often powerless to bring claims as children, often suppress memories as they grow older and typically don’t come forward with their allegations until they reach their 50s.

“If this court struck down this legislation, it would be treating a so-called ‘vested’ right as superior to all fundamental rights protected by the Constitution,” Gauthier told the justices. “There's no basis in law or logic for doing that.”

Kathryn Robb, executive director of Child USAdvocacy, has helped advocate for lookback windows in more than a dozen states, including Louisiana. She said the Supreme Courts in those states have upheld their constitutionality in almost every case where it was challenged. The only exception so far: Utah.

“The reason why we need these types of laws and revivals is because of the nature of trauma, because the perpetrator silences the victim and it takes some years to come forward,” she said. “Our laws have to reflect the science. The laws should also reflect what we know is a perverse, pervasive problem of one in five girls and one in 13 boys being sexually assaulted before their 18th birthday. I mean, if that's not an epidemic, I don't know what is.”

Kristi Schubert, an attorney who filed the first lawsuit under the lookback window in 2021 and represents dozens of similar claims, said it makes no sense to argue that an old deadline that forced a 5-year-old victim of sexual abuse to file a lawsuit at age 6 or lose that right forever could not be fixed by the Legislature.

“Most states that have addressed this exact question have determined that these types of laws -- revival cases -- do not violate the Constitution,” Schubert said. “But what we're really talking here about is the Louisiana Constitution. And there is nothing in the Louisiana Constitution that says that the right to say ‘too late to sue me’ can't be taken away.”

Schubert and Robb joined with abuse survivors gathered outside the historic Supreme Court building in the French Quarter before and after the oral arguments.

“This whole bill today is all about us having a lookback and saying, ‘Y'all can't run anymore,’” said Stephen McEvoy, who is one of more than two dozen men and boys who alleged Catholic deacon George Brignac sexually abused them in the 1970s and 1980s.

“It's time for these survivors to find closure in their lives,” said John Anderson, another Brignac victim.

Brignac died in 2020 while awaiting a criminal child molestation trial that was delayed by the Covid pandemic.

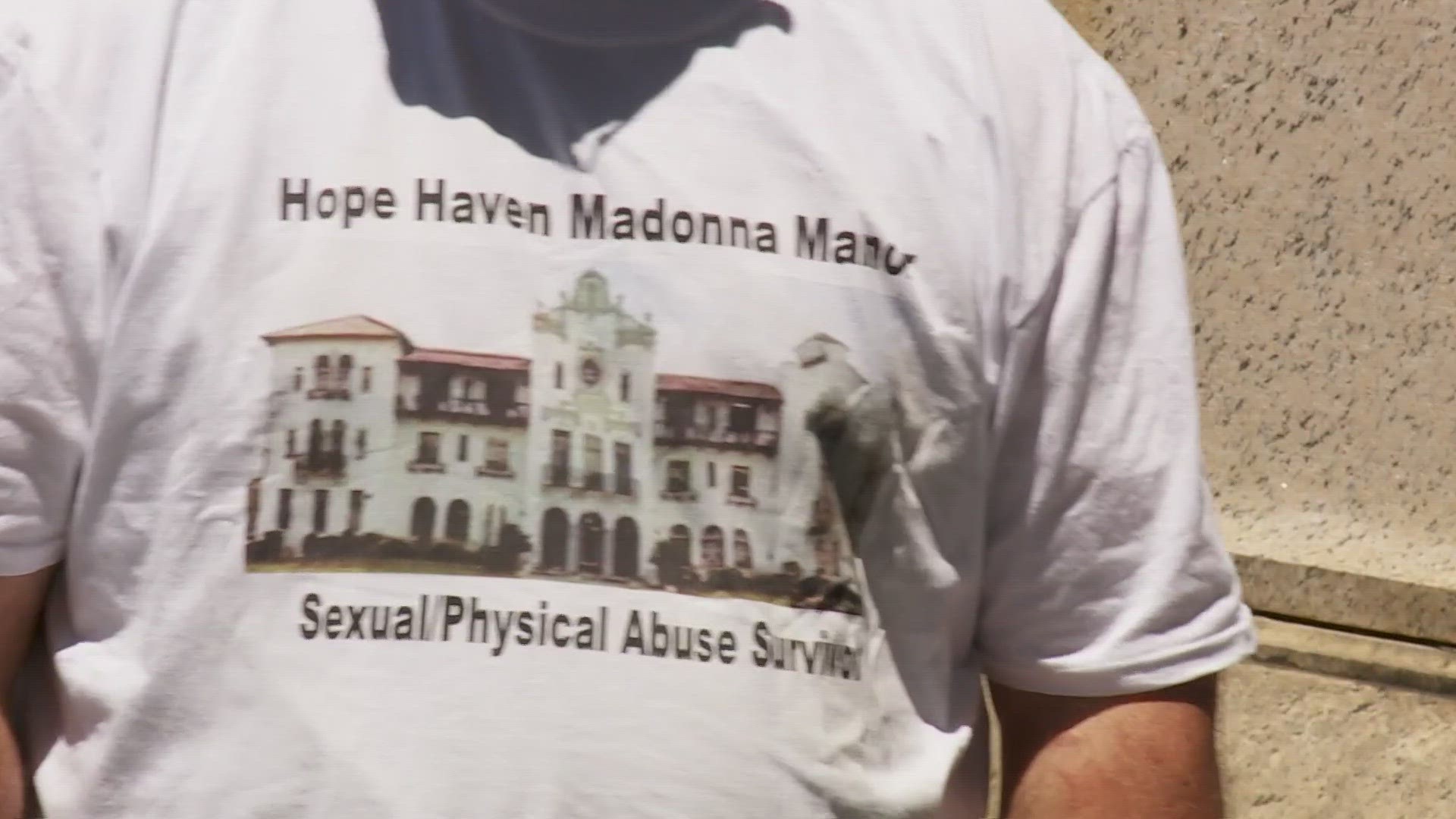

Two brothers, identified only as John Roe Number 1 and John Roe Number 2, also came to the Supreme Court on Monday. They allege they were sexually abused by priests and staff at the Catholic orphanage Madonna Manor in Marrero.

“We want them to pay for their sins,” John Roe 2 said.

► Get breaking news from your neighborhood delivered directly to you by downloading the new FREE WWL-TV News app now in the IOS App Store or Google Play.