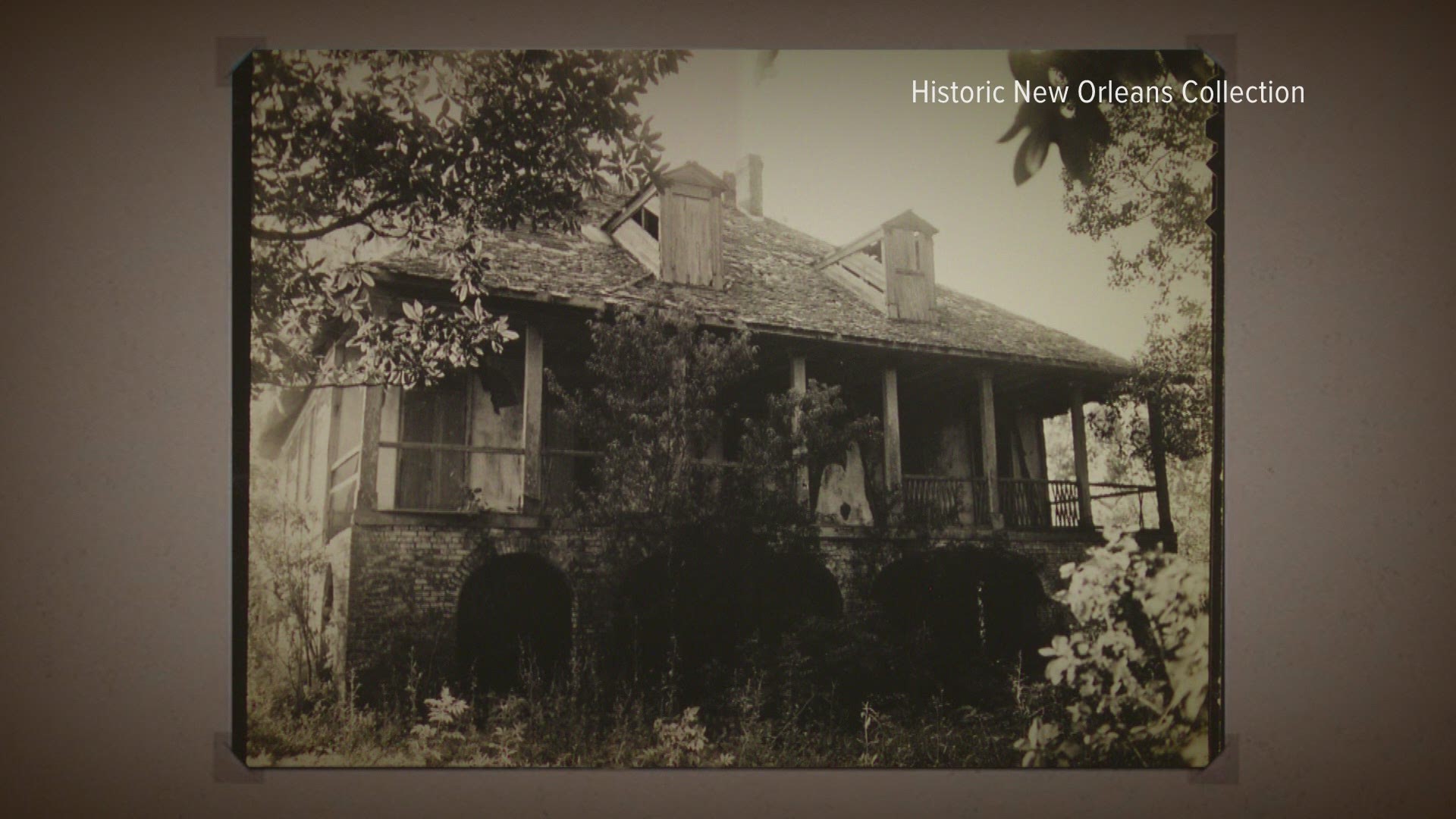

PLAQUEMINES PARISH, La. — Thick woods overtook the old St. Rosalie Plantation house more than 70 years ago.

But to the people of Ironton, a community of modest homes just south of those woods, St. Rosalie remains a powerful symbol of Black heritage in the heart of what used to be a bastion of White supremacy -- Plaquemines Parish.

And now, plans to build a new oil export facility on St. Rosalie are raising concerns about whether a key part of that heritage could be erased.

Nearly 200 years ago, a free Black man named Andrew Durnford owned and operated a sugar plantation at St. Rosalie, along the west bank of the Mississippi River. Durnford died a few years before the Civil War and left the plantation to his widow and children. Records show the Durnfords enslaved Black workers, but also paid them wages during the Civil War.

Once emancipated, those workers founded the town of Ironton just south of the plantation.

Durnford and his family were laid to rest in above-ground tombs in one spot on the St. Rosalie property, close to where La. 23 now passes by. About a quarter-mile closer to the river, enslaved people were buried in an area of unmarked graves.

The existence of the historic graves was no secret. Documents stored in the Tulane University Archives include lists of workers’ names and references to the enslaved people who died at St. Rosalie. Official maps in the 1920s and 1940s clearly marked two cemetery locations, and Ironton residents who hunted in the woods there knew exactly where the burial grounds were.

“We would see the graves,” said Wilkie DeClouet, a retired Jefferson Parish sheriff’s deputy who lives in Ironton. “We knew the graves was there, but we know to go around and you respect that kind of stuff.”

But DeClouet and his neighbors have witnessed plenty of disrespect for those cemeteries over the years. And recently, they feared the parish’s thirst for industrial development would lead to a final desecration.

In 1977, Louisiana Power & Light was preparing to build a nuclear power plant at St. Rosalie when the utility’s bulldozers crushed the Durnford family tombs. Plaquemines Parish historian Rod Lincoln said LP&L blamed “treasure seekers” for using the bulldozers when they were left near the tombs over a weekend.

To DeClouet, it sounded like an excuse for one of many failed attempts over the years to build on top of a sacred place.

“They're going to blame it on vandalism. It wasn't vandalism,” DeClouet said.

Again and again, major projects have been planned at St. Rosalie, but none have come to fruition. A Colorado company wanted to build a coal export terminal there, but walked away in 2018.

At that point, the Plaquemines Port and Harbor District, a public agency, purchased the old St. Rosalie property for $30.5 million. Plaquemines Liquid Terminal, a joint venture of Tallgrass Energy and Drexel Hamilton Infrastructure Partners, put up the money.

PLT now leases the site and plans to build a $20 million oil export terminal there, complete with railroad service, massive oil tanks and underground pipelines to receive oil and transfer it onto seabound tankers that can dock on the river.

By law, PLT had to research the site and determine if any historic cemeteries still exist there. That process began two years ago, according to records filed with the State Historic Preservation Office.

Archaeologists and other investigators found almost 13,000 artifacts from the plantation, including pieces of inscribed tombstones, wood and screws from coffins and three pieces of human bone.

In July 2020, archaeologists hired by PLT filed another report with the state pinpointing the two historic cemetery locations and recommended avoiding construction on those areas. But in the same report, PLT indicated it still planned to build two oil storage tanks on top of the location identified as the main cemetery for enslaved people, and another tank less than 25 feet from the location identified as the Durnford family plot.

Audrey Trufant Salvant, a former Plaquemines Parish councilwoman who traces her Trufant ancestors back to the founding of Ironton and likely to the enslaved people at St. Rosalie, has been warning parish officials about the cemeteries for decades. She and other residents started sounding the alarm again as soon as PLT introduced its development plans in 2018.

“There were community meetings that were held here at the local church and all members attended and we informed them of our knowledge of cemeteries on that property,” Salvant said.

She said the Port’s executive director, Sandy Sanders, attended those meetings. But Sanders told WWL-TV in an interview that he only recently learned about the cemeteries’ existence.

“They didn't say cemeteries,” Sanders insisted after a Jan. 28 Port Commission meeting. “I mean, they said it's been over there for over 200 years. So, you figure you're going to find something.”

Sanders said he didn’t learn about the cemeteries until October, when Tallgrass and its contracted archaeological team from ELOS Environmental notified the Port staff about three human bones. The port’s deputy director, Paul Matthews, sent an email to port commissioners listing the 13,000 artifacts. It noted there were three human bones but said nothing about a cemetery.

'It's our heritage'

The Port Commission is comprised of the nine elected parish council members. The commission’s chairman, Richie Blink, said he first learned about the cemeteries in December, when a member of the public sent him the archaeological reports.

In an email to Blink after the Jan. 28 meeting, Sanders asked Blink to share his copies of the archaeological reports.

“We would appreciate everyone having the same information regarding this matter,” Sanders wrote.

When Blink said a member of the public had provided him with the records, Sanders questioned how because he believed it was “privileged information.”

Blink said he’s baffled by the air of secrecy surrounding the project. Sanders sent an email to PLT officials in December suggesting they hold two separate meetings with port commissioners to update them on the PLT project "so as not to bump into more than 4 commissioners together at one time."

Such a setup is called a “walking quorum” and is a violation of the Louisiana public meetings law, according to the Attorney General’s Office.

At the Port Commission’s Jan. 28 meeting, Tallgrass Vice President Craig Meis offered a public explanation of the archaeological investigation for the first time. He also apologized to commissioners for not keeping them apprised of the cemetery findings.

But Meis and representatives from ELOS told the commissioners they were not trying to keep those findings secret. The reports Blink and WWL-TV obtained from public records requests will still be considered drafts until they are approved by the State Historic Preservation Office. ELOS Vice President Jay Prather said the reports will be provided to the commissioners when the final draft is approved.

Sanders told WWL-TV the port will not allow the PLT development to move forward with building any oil tanks on the cemetery sites. It was never going to allow it, he said.

“We would never put a tank down on top of that; never,” Sanders said. “And we would certainly enshrine it, and (be) proud of it. It's their heritage. It's our heritage.”

But Salvant remains dubious.

“There's always an issue, always an industry to come in,” she said. “And you would think that the government would have your back. But that's never the case.”

This time, however, Blink says there’s a new attitude about racial justice on the council. He openly acknowledged the systemic racism that made Ironton one of the last communities in the U.S. without running water or sewer service.

“This community didn't get in running water until 1980, and they had to fight tooth and nail to get it,” Blink said. “I mean, they were systematically held back.”

It’s not clear how PLT will alter its plans for the site, but Blink says he wants to make sure the burial sites are protected and accessible to descendants.

“I mean, you wouldn't go bulldoze St. Louis No. 2 to build a casino or something,” he said, referring to one of the many revered historic cemeteries in New Orleans. “These folks here, they don't want a tank built on top of their grandfather's grave.”

► Get breaking news from your neighborhood delivered directly to you by downloading the new FREE WWL-TV News app now in the IOS App Store or Google Play.