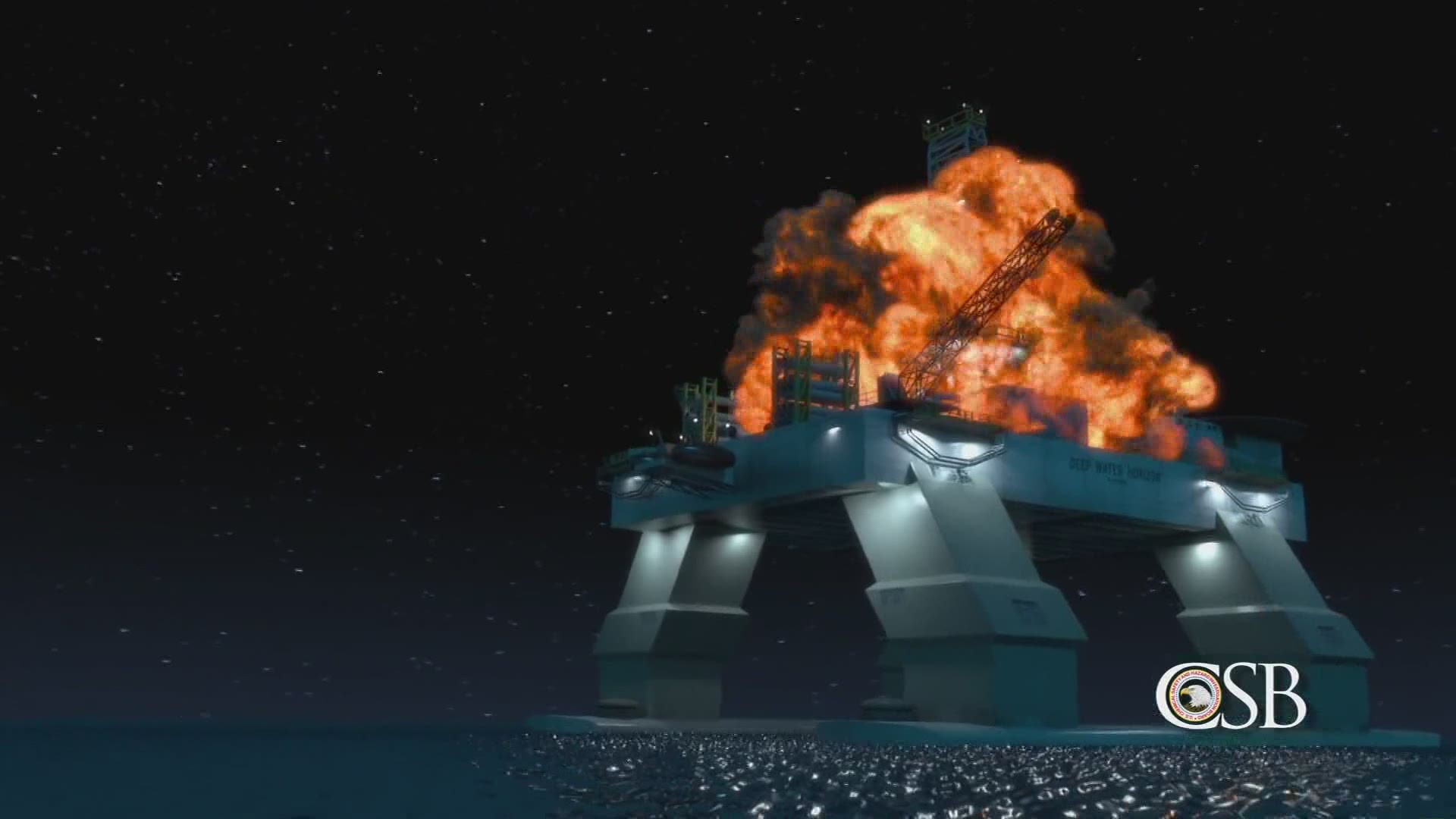

NEW ORLEANS — Christopher Pleasant sat before a packed ballroom in Kenner 11 years ago and told a government investigative panel how he had tried to save the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig a month earlier, as massive fireballs engulfed the vessel.

“I said, ‘I’m EDS’ing.’ The captain told me, he said, ‘Calm down, we’re not EDS’ing,’” Pleasant said on May 27, 2010, his thick, slow drawl captivating the room and a national TV audience on C-SPAN.

Pleasant, the subsea supervisor on the rig, had tried to activate the EDS, or emergency disconnect sequence, to unlatch a mile-long pipe called a “riser” connecting the floating Transocean rig to an oil well the crew had just drilled for BP, about 50 miles southeast of Venice.

But it was too late. The well was already blowing out, beginning the worst oil spill in U.S. history. Pleasant’s hydraulic controls for disconnecting were destroyed by the force of the explosions, the device for closing off the wellhead didn’t function properly and 11 of his co-workers on the rig were incinerated.

Dangerous Déjà Vu

Fast-forward to Oct. 28, 2020, and Pleasant found himself in another dangerous situation. This time, he was on a different drillship also owned by Transocean, called the Deepwater Asgard. This time, the well the crew was drilling sat 180 miles due south of Morgan City in the oil and gas lease block known as Green Canyon 895. This time, instead of a blowout, 100-mile-per-hour winds and 30-foot seas from Hurricane Zeta were knocking the drillship dangerously out of position, bending the riser pipe near its breaking point.

As he had on the Deepwater Horizon, Pleasant operated equipment on a well about a mile below the Gulf’s surface. Again, the ship was connected to the well by a riser pipe that had to disconnect from the well in a hurry. Again, there were allegedly disputes between the crew and managers about the safety of continuing the drilling operations.

But this time, Pleasant wasn’t too late. The EDS was activated and the Asgard disconnected from the well.

The ship lost engines it used to keep steady over the well. The storm knocked the ship into shallower water, causing a key piece of equipment to slam into the sea floor and the top part of the riser pipe to hit the ship’s hull and rupture. But the well was safely shut-in, no oil was flowing into it, the ship wasn’t latched onto it and nobody got hurt.

“They were extremely lucky,” said Jeff Hagopian, a former drillship captain who runs safety training for the U.S. Navy. “I can only imagine how frustrating that must have been for (Pleasant), because I'm sure he's reliving that once again our safety is being compromised for other interests.”

Not a lot of attention

Unlike the Deepwater Horizon catastrophe, which captivated the world for the whole summer of 2010, the Deepwater Asgard incident got very little attention and no mainstream media coverage. But Hagopian and others say what happened on the Asgard is worrisome and seems to indicate that profits still trump safety in offshore drilling operations.

According to an official government report on the incident, the small oil company that owned the well, Beacon Offshore Energy, reported a “kick” – fluids getting into the well from potential oil and gas deposits in rock formations near the well – on Oct. 24, just four days before the incident. The crew had to take time to repair the walls of the well to make sure nothing more could leak into it.

The report also refers to the problems on Oct. 24 as “ballooning,” which is an influx of drilling mud flowing back into the well from the rock formation. Representatives from the oil company and Transocean believe there was no reservoir of oil that could have leaked into the well.

Regardless, to be safe, Beacon had an additional barrier placed in the well when it became clear early on the morning of Oct. 27 that Zeta was a hurricane, could become a major one and was heading straight for the Asgard.

The crew pulled the drill out of the hole and closed off the wellhead in preparation to unlatch from the well and move out of the storm’s path, according to a lawsuit filed by Pleasant against Transocean and Beacon Offshore.

'Strongly Disagree'

And yet, Pleasant alleges the captain ordered the crew to stop the unlatch process until he could speak with shoreside managers in Houston at 4 p.m. Oct. 27.

“At the 4:00 p.m. phone call, Transocean and Beacon ordered the vessel to stay latched despite Hurricane Zeta headed directly toward them,” the lawsuit states.

Pleasant and other crewmembers “strongly disagreed with the decision to stay latched but had no other options but to obey orders,” the lawsuit continues.

The implication is that the on-shore managers were more concerned about losing time and the costs Beacon was paying Transocean every day it was there to drill the well, than they were about safety. And Hagopian, as a former captain, said the captain should have stood up against that.

“I believe the captain failed them, failed his crew in not telling management, ‘No, this is not safe for us to remain here. We need to go,’” Hagopian said.

About 18 hours later, shortly before 10 a.m. on Oct. 28, Zeta’s eyewall passed directly over the Asgard and almost snapped the riser pipe like a twig.

“Why are you questioning the person that is actually out there, seeing the conditions, understanding what's happening, (deferring) to a bunch of people that are worried about profits and whether they can stay on schedule and whether they're going to get their bonuses?” said Scott Bickford, a maritime attorney who is not involved in the Asgard litigation but represented one of Pleasant’s crewmates on the Deepwater Horizon, electrical engineer Mike Williams.

A similar dispute between crew and managers became a focal point of the Deepwater Horizon investigation. Like the Asgsard, the Horizon crew had experienced a kick a few days before they were preparing to leave. When they were closing in BP’s Macondo well, BP managers decided to skip a key test of the well’s integrity 11 hours before the explosion.

Transocean employees, including Jimmy Harrell, the top Transocean drilling supervisor on Deepwater Horizon who died last week, testified that he had to insist that BP conduct another test of the pressure inside the well. That test ended up showing indications of a leak, but BP managers didn’t believe it was a significant problem and decided to move forward without addressing it. A few hours later, the well blew out.

“It's a bit ironic and a bit sad because you know, what lessons were learned?” Bickford said.

Transocean responded to questions about its decisions on the Asgard with a statement from spokeswoman Pam Easton:

“While we do not comment on the details of pending legal matters, we are always committed to safety, the well-being of our employees and responsible operations and believe the facts of this matter will demonstrate that commitment.”

The company noted that forecasts for the path and intensity of Hurricane Zeta changed drastically in the last day and a half as it cleared the Yucatan and sped its way to southeast Louisiana. But the Interior Department reported several other mobile drilling operations in the Gulf had evacuated by Oct. 27 and the Asgard was the only one in the storm’s path that stayed latched.

Beacon Offshore, the owner of the well, declined to comment officially, but a person familiar with Beacon’s operations, who spoke to WWL-TV on condition of anonymity, said Beacon officials were not involved in any phone call with the captain on Oct. 27 and allowed Transocean to make operational decisions.

“The decision to latch or unlatch clearly belongs to Transocean,” the source said. “There would have been extensive dialogue among the relevant parties, what is the safest action to take. Discussion did of course take place, but ultimately it was a call the captain and Transocean made.”

In his lawsuit, Pleasant also alleged that tensioners, equipment used to stabilize the riser pipe, were severely weakened and scheduled to be replaced earlier in 2020 but were left in place “because the defendants (Transocean and Beacon) did not want to stop production.”

The claim is reminiscent of testimony 11 years ago about Transocean deciding not to take the time to inspect its blowout preventer, the fail-safe device that was supposed to close in the well but experienced several mechanical failures.

Transocean didn’t address Pleasant’s claim about the tensioners in its response to WWL-TV. The source familiar with Beacon’s operations said the oil company was told the tensioners were fine until they were damaged in the storm.

CORRECTION: This story and the video attached incorrectly reported that the riser pipe damaged or broke through the ship's hull. In fact, the pipe ruptured where it struck the ship's hull, but the hull itself was not damaged.