Caleb Breaux and Donald Dumas are among tens of thousands of Gulf Coast residents who took jobs cleaning up BP’s oil spill in 2010, trying to save their communities from the full effects of the worst offshore environmental disaster in U.S. history.

Their backgrounds are very different. Breaux, 42, of Lockport, La., is a horticulturalist who owned a landscape nursery when the BP spill started drifting into the Louisiana marsh. Dumas, 66, of Pensacola, Fla., is homeless and was unemployed when BP’s oil hit the white-sand beaches of the Florida Panhandle.

But both ended up getting sick after touching and breathing in the oil and chemicals sprayed on the oil to break it down. Both were excluded from a 2012 medical benefits settlement designed to pay cleanup workers for their medical conditions. And both are among more than 5,000 former cleanup workers who have filed medical claims against BP and have yet to receive compensation.

While millions of Gulf Coast residents have moved on from the devastating environmental and economic damage caused by the BP spill, and tens of thousands of them received compensation from BP for their financial losses, many of those who were directly in contact with the oil spill are still waiting for compensation or, worse, are now being turned away.

Not even one has convinced a federal court to hold a trial on the merits of a medical claim. And only one plaintiff in Tennessee has managed to settle with BP out of court.

Workers to blame?

BP now argues in hundreds of cookie-cutter responses filed in federal courts across the Gulf Coast that the workers’ own negligence caused their injuries or the contractors BP hired to run the cleanup operations could be liable for any injuries, even though the 2012 settlement specifically locked claimants into suing only BP and its affiliates.

BP spokesman Paul Takahashi declined to comment on the specific claims in this story, citing the company's policy of not commenting on active litigation.

BP also has crucially changed its stance on whether its oil and the cleanup chemicals could have made people sick.

Back in 2012, BP agreed in the medical settlement to pay cleanup workers and coastal residents between $1,400 and $60,700 for specific conditions that BP admitted could have been caused by exposure to the oil and cleanup chemicals.

But more than a decade later, federal court records show 22,800 claimants received an average of less than $3,000 each, mostly for acute conditions like conjunctivitis, sinusitis and skin rashes that were diagnosed soon after the cleanup was done and quickly went away.

When did the problems get diagnosed?

Only 40 of those claims were approved for chronic conditions that merited maximum payments of $60,700.

That's because of a dispute about what one word in the settlement meant.

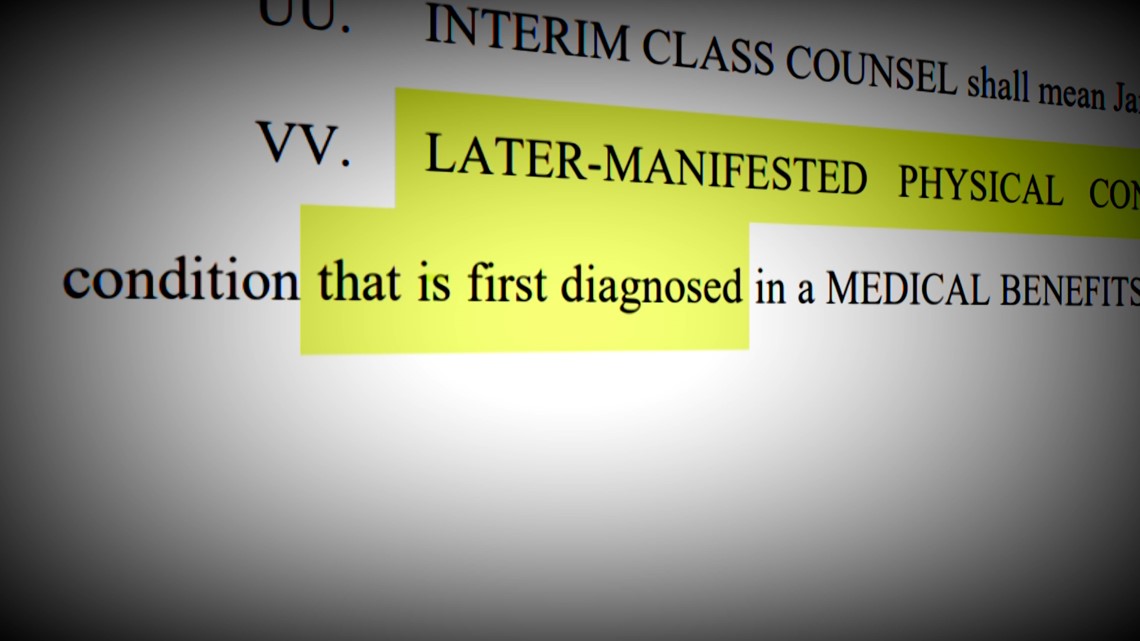

In 2012, BP and the plaintiffs agreed in a court hearing that anyone whose condition "manifested” before April 16, 2012, could get paid. The agreement said anyone whose condition was "later-manifested" – after the April 16, 2012 date -- would have to sue BP later, and prove, one by one, that BP's oil and chemicals caused his or her specific injuries.

But in 2014, BP went back to court and noted the settlement defined a “later-manifested physical condition” as one that was “first diagnosed … after April 16, 2012.” The company used that interpretation to argue it didn't matter when the condition first appeared, but only when it was diagnosed by a doctor, and only if it was specifically recorded as being chronic.

Plaintiffs’ attorneys argued that was never their intent when they signed the settlement. They said “later-manifested” was supposed to refer to cancer and other conditions that develop over time, with a latency period after exposure, not to chronic conditions that showed up immediately but couldn’t be diagnosed as chronic until they had lingered for a while.

But the plaintiffs, led by New Orleans attorney Steve Herman, acknowledged that they had inserted the word “diagnosed” into the settlement. Herman later told WWL-TV it was a mistake.

U.S. District Judge Carl Barbier stated from the bench that the new interpretation wasn’t what either party intended and would force huge numbers of settlement members out of the settlement. But he concluded the plain meaning of the agreement language was clear and BP’s interpretation was correct.

Skin and vision issues that continue

Dumas is one of thousands who bore the brunt of that decision. He claimed he suffered ocular issues almost right away while working on Johnson Beach in Perdido Key, Fla. After his four-month stint was over in the fall of 2010, Dumas said he couldn’t afford to go to a doctor because he had no money and no health insurance.

He did get a diagnosis of chronic conjunctivitis on Aug. 25, 2012, but that was four months too late for the April 16, 2012 diagnosis deadline.

From 2018 to 2021, more than 4,000 lawsuits alleging BP caused later-manifested conditions were thrown out of court, according to federal court records. One was Dumas’ case, which was dismissed in a batch of 28 cases by the Northern District of Florida in December 2021.

The judge ruled those claimants had received workers’ compensation for some of their injuries and that made them ineligible for collecting compensation for later-manifested conditions under the settlement. Dumas’ attorney, Allen Lindsay of Milton, Fla., said those claimants never made a workers’ comp claim for their chronic conditions, just their acute illnesses. But his appeal in Jacksonville last year was rejected.

A magistrate judge who recommended dismissing those claims states in his opinion that the claimants all had conditions that “manifested” after April 2012, contrary to sworn statements from the plaintiffs that their ocular issues showed up immediately but weren’t diagnosed until later.

“I think that's wrong. Dead wrong,” Dumas said. “And I think they was wrong for not telling us the damage that that oil could do to our bodies all these years. They don't even want to compensate you for nothing.”

Claims for conditions that truly did show up later, including cancer and cardiac disease, have also been rolling into court over the last few years. BP has responded by claiming its oil and chemicals were not toxic enough to have caused those illnesses.

Cancer diagnosis

Breaux, for one, was diagnosed with Stage 4 non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in 2020. He said his oncologist at MD Anderson in Houston told him a chemical caused his cancer. Breaux said he was convinced when he learned the captain of his boat on the offshore cleanup work was diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma just three months later.

Breaux had massive tumors from his neck to his groin. Records show his chemotherapy and other treatments have cost more than $605,000 in two years. Most of those costs were covered by health insurance, but he was laid off recently and lost his insurance. He has new cancer screenings scheduled and he’s still waiting for a hearing in his lawsuit against BP.

“I know they may be tired of dealing with it and they feel they’re done with it,” Breaux said. “But they're not, obviously. I mean, I'm not done with it.”

Plaintiffs’ attorneys with thousands of clients are giving up on their cases. Lindsay said he hasn’t given up on his remaining 150 clients, but he isn’t optimistic.

“Sometimes justice isn't served,” Lindsay said. “That's the real bottom line here.”

But Breaux's attorney, Miami-based Craig Downs, is more bullish on the prospects for hundreds of his clients.

“We're not going anywhere,” Downs said. “We believe it's going to be a good year and we're going to turn the tide on the science.”

Downs and a team of lawyers and scientists have a secret warehouse in Florida that holds 130,000 samples of oil, oil-sand mix, tar mats, tar balls, pieces of personal protective equipment and other items collected from the cleanup sites. The samples are kept in three areas depending on what’s required to preserve them – some in a room kept at 40 degrees Fahrenheit, some in a refrigerated storage unit at -4 degrees, and some in a deep freezer kept at anywhere from -80 to -112 degrees.

WWL-TV agreed not to disclose the specific location of the warehouse. The samples were all collected by BP, mostly in 2010, and catalogued based on date and location of collection. Attorney Dylan Boigris of Downs Law Group said BP was about to dispose of the samples until he and his colleagues stepped in and took possession.

The Downs team is testing the samples again because Boigris said BP used toxicological standards that are now outdated.

“It turns out that regulation kind of lags behind and it doesn't keep up with modern science,” Boigris said. “Now we know that there are lower concentrations of chemicals or maybe trace amounts of chemicals that would have resulted from the spill that were absolutely harmful to the individuals that they were exposed to.”

Downs' chief science officer, Angela Caceres, said the science on toxic exposure is stronger than it was a decade ago. Several new studies following the health of thousands of U.S. Coast Guard oil spill responders found elevated risks for longer-term neurological and cardiovascular conditions. In addition, a study by a team of epidemiologists in North Carolina -- published just three weeks ago in the journal Environmental Research -- found higher risks of coronary heart disease in cleanup workers who were exposed to particulate matter near sites where the oil was being burned on the Gulf surface.

Breaux is putting his faith in Downs and his team. He said he admires the Miami law firm for putting its resources behind the effort and not giving up. And he has one message for BP:

“Live up to your word and take care of us.”

► Get breaking news from your neighborhood delivered directly to you by downloading the new FREE WWL-TV News app now in the IOS App Store or Google Play.