NEW ORLEANS — A 1991 child rape case was derailed in every imaginable way for 27 years, until what seemed to be a final twist helped prosecutors send a 55-year-old mechanic to prison in 2018.

But now, less than four years into Gerard Ladmirault’s 15-year sentence, the case could be thrown out on a timing technicality, a final U-turn that nobody – not the prosecutors, not the defense attorney, not appellate lawyers, not two different judges and certainly not Ladmirault’s accusers – ever saw coming.

A hearing is scheduled for Sept. 12, where a third judge will consider wiping out Ladmirault’s conviction and even the criminal charges filed against him in 2014.

Ladmirault was first arrested in the case in October 1991, accused of holding a knife to 14-year-old LaToya Gaines’ neck and forcing her to perform oral sex. Court records show the girl directed the police to the scene where they found Ladmirault’s buck knife and a towel soaked in semen, just as Gaines had described to them.

Mother asked her to drop charges

But a week later, Gaines signed a document refusing to bring charges against Ladmirault. The case was officially dropped by then-District Attorney Harry Connick Sr.’s office in early 1992. Gaines testified that her mother, a crack addict, had instructed her to drop the charges.

Two decades later, Gaines was dropping off her own child at Warren Easton High School and said she saw Ladmirault bringing a teenage girl to the school. Suddenly, feelings she had locked away for years flooded her mind, and she rushed straight to the district attorney’s office demanding to press charges.

She spoke with Assistant District Attorney Mary Glass, who researched the case and told her she was still in time to reinstate the charges against Ladmirault. Now, however, it appears that was wrong, based on Ladmirault’s legal arguments and WWL-TV’s independent review of documented changes in Louisiana’s Code of Criminal Procedure.

A Question of Timing

The law setting deadlines for prosecuting certain sex crimes was enacted in 1993. It gave the state 10 years from the time a child victim of aggravated oral sexual battery turned 17 – until the victim’s 27th birthday, in other words – to initiate prosecution.

Gaines would turn 27 on July 24, 2004. But in 2001, the deadline for prosecuting certain sex crimes against children was changed, from a victim’s 27th birthday to the victim’s 28th birthday. That gave the state until July 24, 2005, to charge Ladmirault by the time Gaines turned 28.

In the early 2000s, Louisiana’s legislature was slowly recognizing that child victims of sex crimes often lock away the painful experience for decades before something triggers the memory and prompts them to come forward.

On June 29, 2005, then-Governor Kathleen Blanco signed another change in the legal deadline, this time giving victims of child sex crimes 30 years after turning 18 to come forward. The law was signed 25 days before the deadline for Gaines. If it had gone into effect immediately, it would have given the state until Gaines’ 48th birthday – which won’t happen until 2025 – to reopen the case against Ladmirault.

But the new law didn’t take effect immediately upon Blanco’s signature. It didn’t kick in until August 15, 2005.

That was 22 days after Gaines’ birthday – 22 days too late to prosecute Ladmirault.

“And it just helps one worm or one snake slither on through. It's unbelievable,” Gaines said.

No one noticed a problem, but it was there

But nobody seemed to notice. The prosecutors and defense all proceeded as if the charges filed against Ladmirault in 2014 were timely.

That led to two mistrials in 2015 and 2016 in front of Judge Laurie White; a WWL-TV investigation in August 2018 that found key evidence was never presented at those first two trials; a third trial in front of former Judge Keva Landrum-Johnson and a guilty verdict in October 2018; and a 15-year prison sentence in December 2018 that sent Ladmirault directly to Elayn Hunt Correctional Center.

The process also reopened old wounds and brought a false hope of justice for Ta-Tanisha Smith, an Atlanta resident who came in to testify on Gaines’ behalf at all three trials. Ladmirault was charged with raping her at gunpoint, 60 days before Gaines.

Ladmirault was acquitted at a trial in Smith’s case in 1992, where he claimed his sex with the 19-year-old Smith was consensual and testimony about her attire and sexual history was still allowed. But over objections from Ladmirault’s defense lawyer David Belfield, Smith was allowed to testify about her case to establish a pattern of behavior.

In March of this year, Ladmirault filed an application for post-conviction relief, arguing the case was time-barred. He argued the deadline to file charges against him expired on July 24, 2004, when Gaines turned 27. That was based on the statute of limitations for aggravated oral sexual battery established in 1993. Ladmirault apparently missed Act 533 of 2001, which extended the deadline to 10 years after a victim turns 18, rather than 10 years after turning 17.

'I lost it'

A hearing on Ladmirault’s claims was scheduled for July 13, then pushed back to this Wednesday, Aug. 3, in front of Judge Rhonda Goode-Douglas. Ladmirault did not show up via Zoom from Hunt Correctional Center, so Goode-Douglas reset the hearing for Monday, Aug. 8.

She granted Assistant District Attorney Brad Scott's request for a separate evidentiary hearing and set it for Sept. 12, meaning Ladmirault would remain in prison for at least another month.

His former defense attorney said that's an unnecessary delay for a man who shouldn't have gone to prison in the first place.

"The effective date of the statute is in black and white, it will not change. That 22 days is there, so what is the evidentiary hearing going to prove?" Belfield said. "The state of Louisiana blew it at the beginning. And now he has to spend 60 more days of wrongful incarceration to give the state more time? That doesn't seem fair. Whatever needs to be done in this case can be done on Monday."

On July 19, Gaines said she first learned from Scott the whole case might be thrown out. She said she lost it.

“I literally felt like my heart was falling apart to hear him say that there's a strong possibility he could get out and not be charged with anything and not have to register with the sex offenders’ registry and not have to stay away from other people's children. I mean, it's just like… like it never happened.”

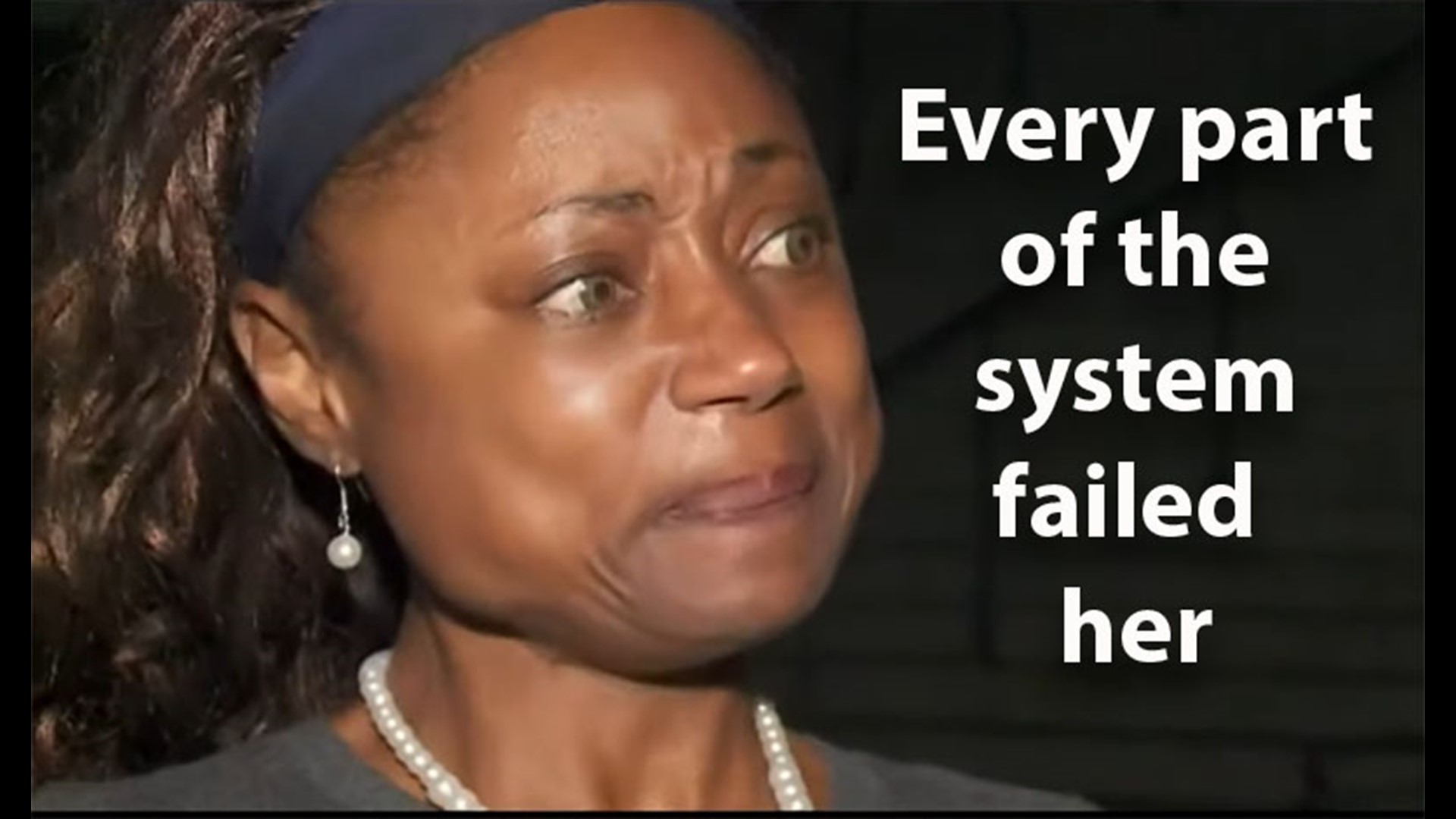

Gaines said she’s livid – at her late mother for stopping the case in 1991; at Connick’s office for not pursuing the case based on the evidence already collected by police; at former DA Leon Cannizzaro’s office for not realizing it was already too late to prosecute Ladmirault when she came forward again 10 years ago.

“I'm not looking for the justice system to say, ‘Oh, we failed. We overlooked a date, but we're sorry,’” she said. “‘Sorry’ doesn't fit.”

She’s also angry at the state of Louisiana for taking longer than many other states to extend the deadline for victims of child sex abuse to come forward.

“The state of Louisiana failed not only me, they failed a lot of people,” she said.

That includes Smith, who had to dig up her own painful memories while trying to get justice vicariously through Gaines’ case.

“We’re still in prison, still dealing with effects, but a predator because of a technicality can walk free and do whatever he wants to do?” Smith said.

But Ladmirault can also argue the justice system failed him, sending him to prison based on criminal charges that never should have been allowed in the first place. In his application for post-conviction relief, he argues the state failed not only him, but Gaines too, writing, “The government … misled the alleged victim, that her claim had not yet proscribed. In fact, the prescriptive period (had) expired 10 years prior.”

He claims his defense attorney at all three trials, Belfield, was “ineffective in representing this case, by not doing a complete investigation of the validity and seeking to expose malpractice or the miscarriage of justice.”

He also argues his appellate attorneys, from the late Martin Regan’s law firm, were “ineffective” for failing to argue on appeal that the charges were filed too late. Regan died in February and his firm declined to comment on a pending case.

Belfield said he may have missed that the case should have been time-barred but so did everyone else, including two different judges, White and Landrum-Johnson.

“If, by chance, there was an error, then I stand by my error and I’m not perfect,” Belfield said. “I believe the application of the law is the primary responsibility of the court. When the court is sentencing somebody to jail, they have to be absolutely sure they are doing it correctly."

“We argue about the law, we argue about the facts, but at the end of the day, it’s the responsibility of the judge to apply the proper law,” he said.

But ultimately, it’s up to the attorneys on both sides to file motions asking the judge to rule on whether a specific law should apply or not.

And that didn’t happen in this case, leaving everyone angry on all sides.

“I wanted the justice system to deal with him,” Gaines said, crestfallen. “And now that the justice system has failed, I'll let God deal with him.”

EDITOR'S NOTE: This story was first published Aug. 2. It was updated Aug. 3 and again on Aug. 8 with new information from court hearings held on those days. The next hearing in the matter is set for Sept. 12.

► Get breaking news from your neighborhood delivered directly to you by downloading the new FREE WWL-TV News app now in the IOS App Store or Google Play.